MyArtBroker Film Reviews: Love Is the Devil: Study for a Portrait of Francis Bacon (1998)

Image © Instagram/ Khalil.Boughali / Bacon and George Dyer, Soho © John Deakin 1950s

Image © Instagram/ Khalil.Boughali / Bacon and George Dyer, Soho © John Deakin 1950s

Francis Bacon

58 works

Key Takeaways

Love Is the Devil: Study for a Portrait of Francis Bacon offers a visceral portrayal of Francis Bacon’s art and life, capturing the chaos, passion, and destruction that defined both. Through its visually fractured narrative, the film mirrors the intense abstraction of Bacon’s paintings, immersing viewers in his nightmarish world. At its core is the tumultuous relationship between Bacon and George Dyer, serving as a meditation on the personal tragedies fueling Bacon’s artistic genius.

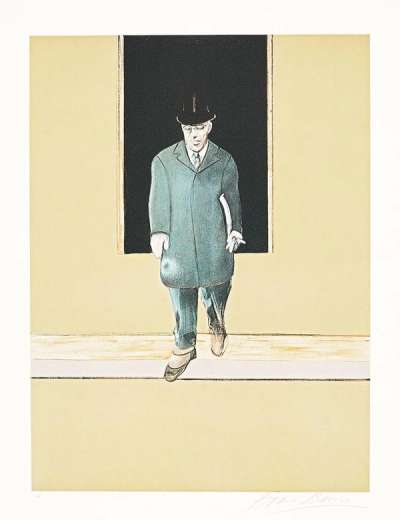

John Maybury’s Love Is the Devil: Study for a Portrait of Francis Bacon is not so much a biopic as it is a living, breathing incarnation of the British artist’s work. Released in 1998, this unconventional film sidesteps the traditional biopic mould, instead embracing a visual language that mirrors the fractured, nightmarish world of Francis Bacon. Both unsettling and mesmerising, at the film’s core lies the destructive relationship between Bacon, played with venomous magnetism by Derek Jacobi, and his lover George Dyer, played by Daniel Craig. Love Is The Devil is a portrait not only of artistic genius, but also of human depravity and emotional destruction - an uncompromising meditation on the price of art and human connection.

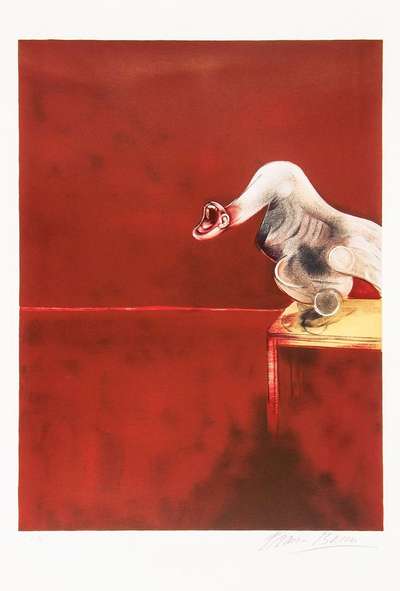

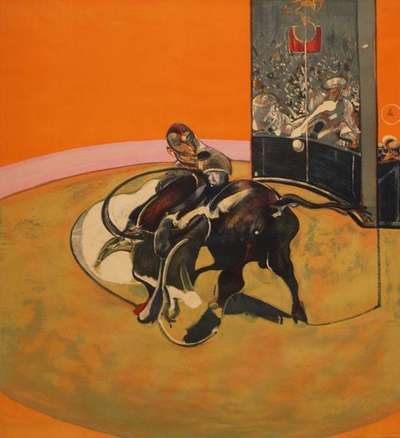

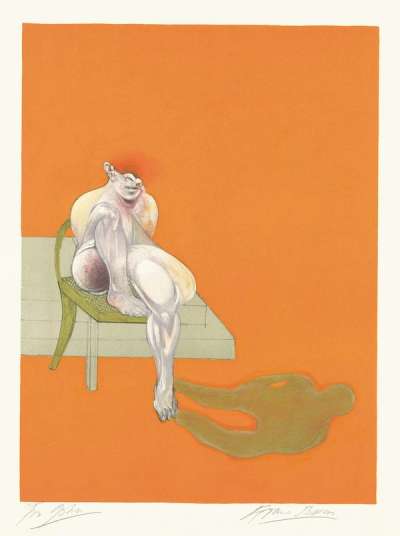

Bacon, one of the most important painters of the 20th century, achieved international recognition for his powerful, often disturbing art. Rejecting the era’s prevailing trend toward abstraction, Bacon forged a distinctive style that combined Surrealist influences, photographic studies, and the emotional intensity of Old Master works. From his early childhood, Bacon’s life was steeped in a chaos and alienation that would later fuel his art. He took inspiration from sources as diverse as Pablo Picasso, whose biomorphic depictions of the human body had a formative influence on him, and Eadweard Muybridge, whose photographic studies of movement shaped Bacon’s exploration of figures in motion.

Image © Ordovas Gallery / George Dyer © John Deakin 1960s

Image © Ordovas Gallery / George Dyer © John Deakin 1960sCinematography: A Baconian Nightmare

The film’s visual and stylistic audacity is its triumph, made all the more impressive by the absence of Bacon’s actual art. Denied permission by Bacon’s estate to feature his works, Maybury and cinematographer John Mathieson instead evoke the essence of Bacon’s paintings through the medium of film itself. The frame becomes a living canvas, distorted with lenses, mirrors, and reflections to create a visual cacophony that feels ripped from Bacon’s world. Faces are stretched, twisted, and warped, often shrouded in shadows or smeared across the screen in a nightmarish haze. This aesthetic isn’t mere mimicry; it’s an extension of Bacon’s artistic process, visualising the chaos and anguish that define his work.

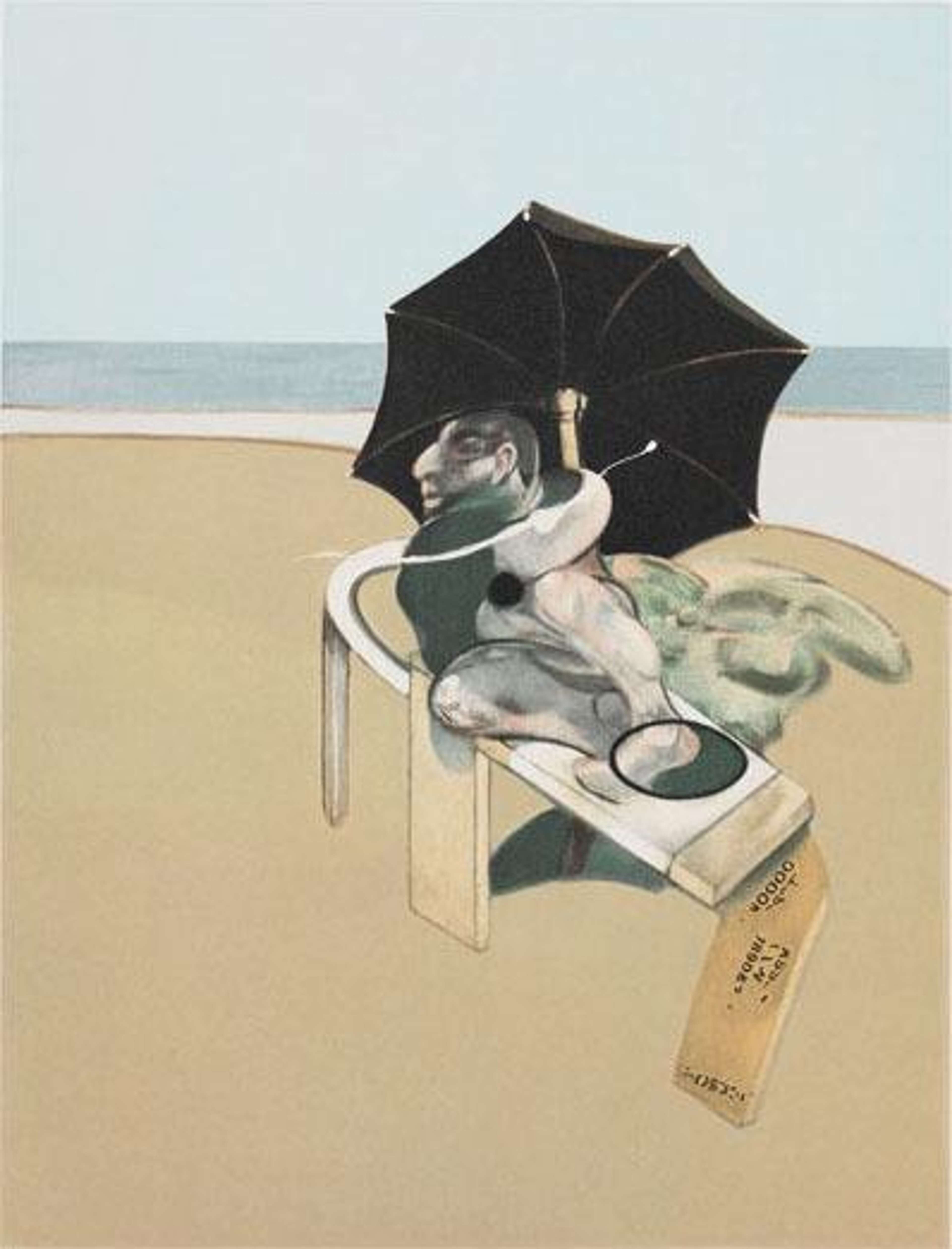

Bacon’s works often depict grotesquely distorted figures, isolated in what he described as “space-frames,” an architectural device used to focus attention and heighten the emotional intensity of his portraits. This concept is echoed in the film’s framing choices, which serve to “concentrate the image down,” a technique Bacon himself employed to strip away narrative context and foreground raw emotion. Ryuichi Sakamoto’s brilliant score heightens the suspense, magnifying the film’s psychological intensity. Moments of surreal abstraction blend seamlessly with realism, pulling the audience into a hallucinatory world where the boundaries between reality and imagination blur.

While the aesthetic is breathtaking in its fidelity to Bacon’s disfigured human forms and chaotic textures, it can also be exhausting. The visual disarray underscores the tumultuous nature of Bacon’s relationship with Dyer, echoing the disjointed emotional landscape that fueled much of Bacon’s art. His triptychs, such as Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), famously depicted humanity’s capacity for violence and self-destruction, themes that resonate throughout the film. Maybury’s direction masterfully simulates the disorienting experience of standing before one of Bacon’s canvases, bringing a sense of dread, fascination, and grotesque beauty to every frame.

Tragedy Through Performance

The film’s strengths lie in its two towering performances. Jacobi’s Bacon is genius but callous, a narcissistic hedonist who objectifies Dyer as both subject and possession. His portrayal reveals Bacon’s dualities: the charm and coldness, the sensitivity and cruelty, the hedonistic excesses, and the obsessive dedication to his art. This duality mirrors the contradictions in Bacon’s life, where his relentless pursuit of emotional truth in his art seemed in sharp contrast to his personal relationships. Meanwhile, Craig delivers a moving performance as Dyer, capturing his vulnerability, instability, and gradual unraveling under Bacon’s carelessness. In Love Is The Devil, their relationship becomes a microcosm of the themes that dominated Bacon’s art: suffering, isolation, and the brutal beauty of human despair.

Bacon’s relationships were often turbulent, shaped by his complex personality and the volatile world of London’s post-war bohemia. He surrounded himself with muses, lovers, and companions, many of whom shared his proclivity for excess and self-destruction. Dyer, a petty criminal from London’s East End, entered Bacon’s life in the 1960s and quickly became a central figure in both his personal life and his art. Their relationship was fraught with imbalance: Bacon was an established artist at the height of his fame, while Dyer struggled with feelings of insecurity, and dependence on both Bacon and alcohol.

Dyer’s tragic arc mirrored the existential themes of Bacon’s art. His figures - distorted, fragmented, and trapped within cage-like structures - can be read as visual metaphors for Dyer’s own feelings of entrapment, both within Bacon’s world and within himself. After Dyer’s death by suicide in 1971, Bacon turned his grief into art, creating a series of triptychs that immortalised Dyer’s memory while grappling with the haunting guilt and sorrow of their shared history. Works, such as Triptych - August 1972, are suffused with an overwhelming sense of loss and futility, the recurring presence of ghostly figures and shadowy voids reflecting Bacon’s inner turmoil.

The film captures this dynamic with devastating clarity, presenting Dyer as both muse and victim. Bacon once described his work as an attempt to “distort the thing far beyond the appearance, but in the distortion to bring it back to a recording of the appearance.” In his paintings of Dyer, this philosophy takes on a deeply personal dimension: the distortion of Dyer’s figure on the canvas reflects both the artist’s anguish and the indelible mark of Dyer’s influence on his work. Through Jacobi and Craig’s performances, Love Is the Devil not only illuminates the psychological underpinnings of Bacon’s work, but also underscores the cost of such unflinching artistic honesty - both for the artist and for those closest to him.

While Love Is the Devil is ostensibly a biopic, it is less a chronological account of Bacon’s life than a study of his destructive relationship with Dyer. Through its fractured narrative and oppressive tone, the film captures the essence of Bacon’s art through its relentless tone and its refusal to soften the sharp edges of its subjects. Bacon’s world, with its garish highs and crushing lows, is presented as an unflinching panorama of self-destructive excess, leaving little room for tenderness. His canvases, which borrow from Surrealism and the dynamism of photography, are recreated and personified in this painful love letter to self-destruction. At its heart, the film reflects the dualities that defined Bacon: beauty and horror, love and cruelty, creation and destruction. Maybury’s film may not be an easy watch, but it is a compelling take on one of modern art’s most compelling and controversial figures.