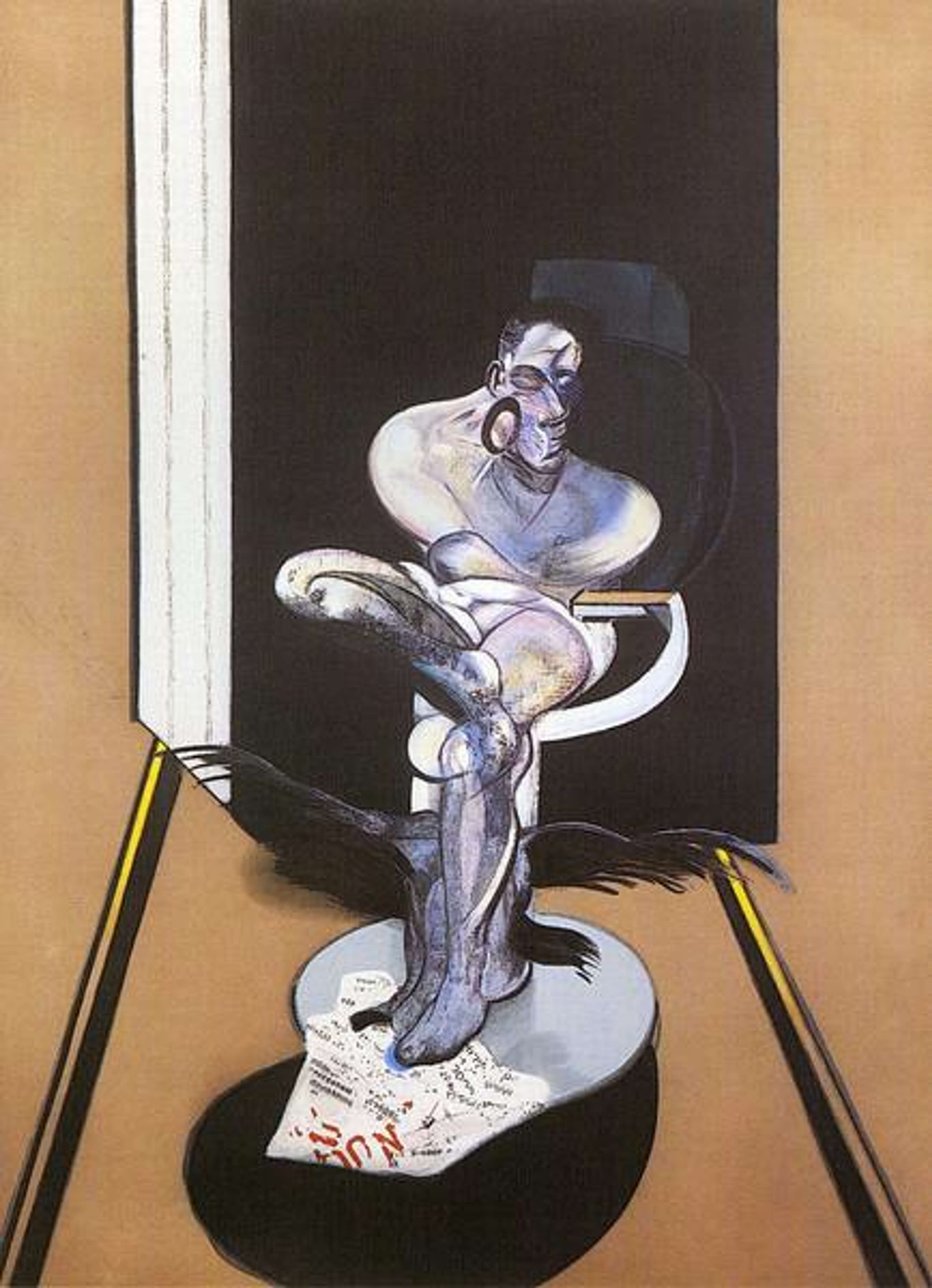

Figure Writing Reflected In A Mirror © Francis Bacon 1976

Figure Writing Reflected In A Mirror © Francis Bacon 1976

Francis Bacon

58 works

Key Takeaways

Francis Bacon drew inspiration from a range of artistic influences that shaped his distinctive style. From Picasso's fragmented forms, to the psychological depth of Rembrandt's portraits, Bacon fused and transformed the techniques of masters to create his emotionally charged, distorted representations of the human condition. These artist's work profoundly impacted Bacon's vision, helping him redefine modern portraiture through a blend of abstraction, motion, and intense emotional expression.

Francis Bacon is renowned for his brutal, emotionally charged paintings that blend abstraction with raw depictions of human vulnerability. His work, characterised by distorted forms and a dark, visceral intensity, transcends traditional portraiture by portraying not only the physical form, but also the psychological and emotional turmoil within. While his art appears fiercely original, Bacon’s distinctive approach was shaped by a myriad of influences, including the Old Masters and modern pioneers of artistic movements, whose innovative methods and exploration of human emotion profoundly shaped his vision.

Pablo Picasso: Bacon’s Gateway to Modern Art

Bacon’s artistic journey was deeply influenced by the work of Pablo Picasso, a towering figure in modern art. Bacon’s first encounter with painting was sparked by an exhibition of Picasso’s works in Paris in 1927, particularly his Cubist and Surrealist works, which had a profound effect on Bacon’s decision to pursue painting. Picasso’s distorted, fragmented human forms, especially those from his surrealist period, captivated Bacon. He was particularly fascinated by how Picasso could distort the human body, bending it into abstract shapes while still retaining its inherent humanity.

Picasso's surrealist works from the late 1920s and early 1930s, with their fluid, organic forms, had a lasting impact on Bacon’s representations of the body. Bacon saw in Picasso’s approach the potential to depict the human figure not merely as a physical entity but as a vessel for psychological and emotional depth. For example, Picasso's surreal beach scenes from the late 1920s, which presented distorted, organic forms, were a key source of inspiration for Bacon’s biomorphic figures in his seminal work Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944). While Bacon eventually sought to escape Picasso’s shadow, Picasso’s influence remained evident throughout his career, particularly in his treatment of the human figure as something mutable and grotesque, yet profoundly expressive.

Diego Velázquez: The Influence of Portrait of Pope Innocent X

One of the most significant influences on Bacon’s work came from the Spanish master Diego Velázquez, particularly his Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650). Bacon was drawn to this painting and its depiction of authority, isolation, and underlying psychological tension. The regal yet menacing figure of the Pope fascinated Bacon, and he reinterpreted the image repeatedly in his series of Screaming Popes, distorting the original image into nightmarish visions of anguish and torment. Velázquez’s baroque realism served as a significant influence on Bacon’s expression of existential terror, turning a symbol of religious and political power into one of human suffering.

Unlike Velázquez’s precise realism, Bacon infused his Popes with violence and distortion, using dark tones, blurred brushstrokes, and raw emotion to convey suffering and despair. In Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953), the face of the Pope is blurred, disfigured, and violently abstracted, evoking a scream of despair. These re-imaginings were less about capturing the physical likeness of the Pope and more about evoking the intense psychological pressure of power, the isolation that accompanies authority, and the vulnerability of the human condition. Bacon's Pope paintings are a dramatic departure from Velázquez's restrained approach, transforming the figure into a symbol of existential angst. Through these works, Bacon redefined the role of the portrait in modern art, using the human figure as a vessel for broader existential themes.

Eadweard Muybridge: Motion and the Fragmentation of the Body

Bacon’s visual language was profoundly shaped by the vast array of photographic material he amassed in his chaotic London studio. When this collection was transferred to The Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin in 1998, art historians uncovered over 4,000 items that revealed significant insights into his working process. Despite Bacon’s efforts to downplay the importance of these sources, it is now evident that his distinctive imagery often drew directly from photographs and cinema, with elements such as body outlines, proportions, and spatial arrangements adapted with precision. Cinema also played a role in inspiring Bacon’s art, one example being the iconic still from Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 silent film The Battleship Potemkin, depicting a screaming nurse during the Odessa Steps massacre, which profoundly impacted Bacon. He cited the image as a key catalyst for his art, inspiring his recurring motif of the ‘screaming figure’ and influencing the visceral emotional intensity and distortion seen in many of his works.

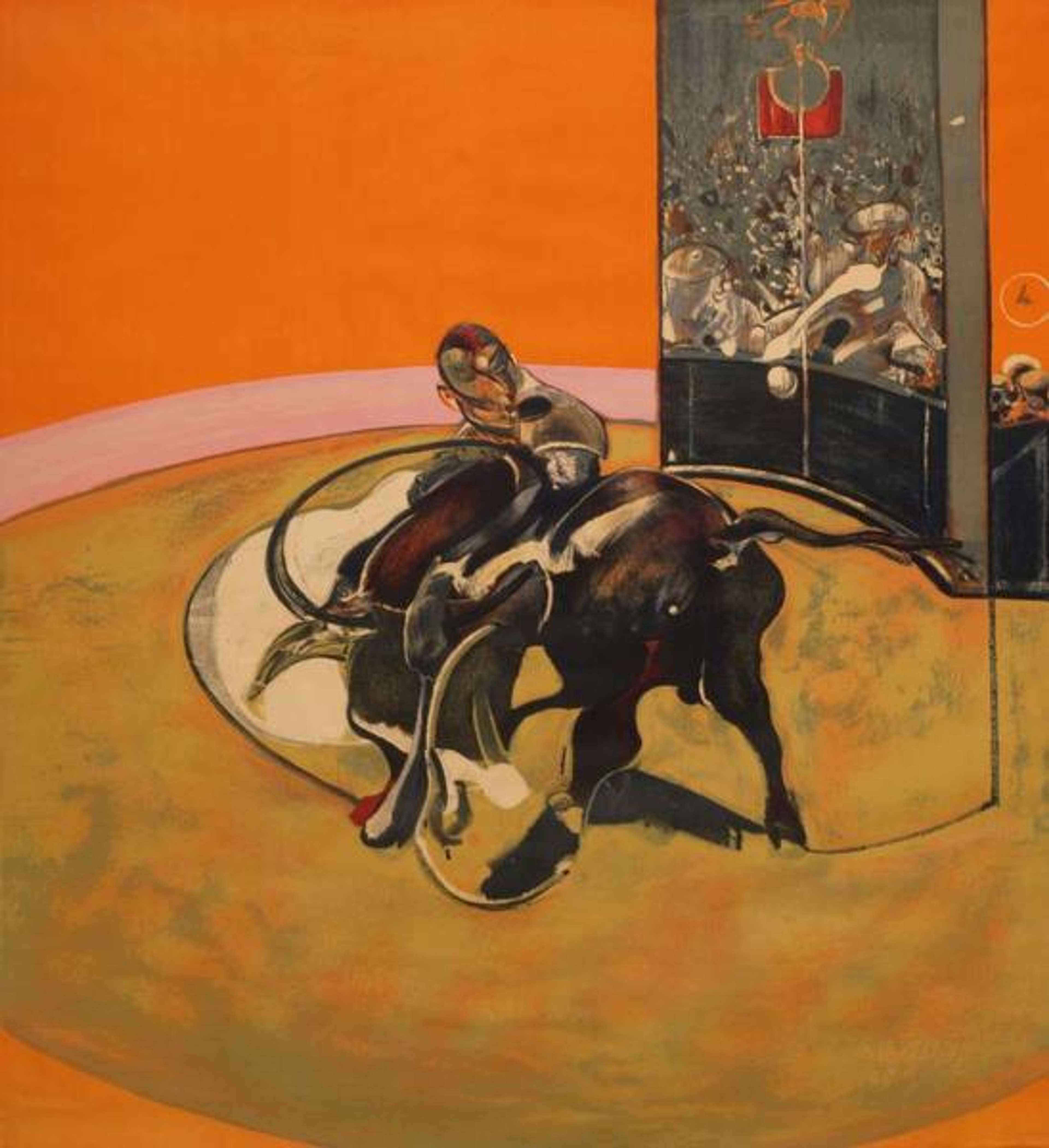

Bacon’s interest in the human body was also informed by the groundbreaking work of Eadweard Muybridge, a pioneer of motion photography. Muybridge’s sequential photographs, which captured the body in various stages of movement, helped Bacon explore the fragmented, transitional nature of the human figure. In paintings such as Study Of A Dog (1953), the body is not static but dynamic, layered with movement and emotion. Muybridge’s work allowed Bacon to explore the concept of the body in flux, constantly changing and never fully whole. This sense of disjointedness and fragmentation became a hallmark of Bacon’s style, as he often portrayed his figures as contorted, trapped between motion and stasis.

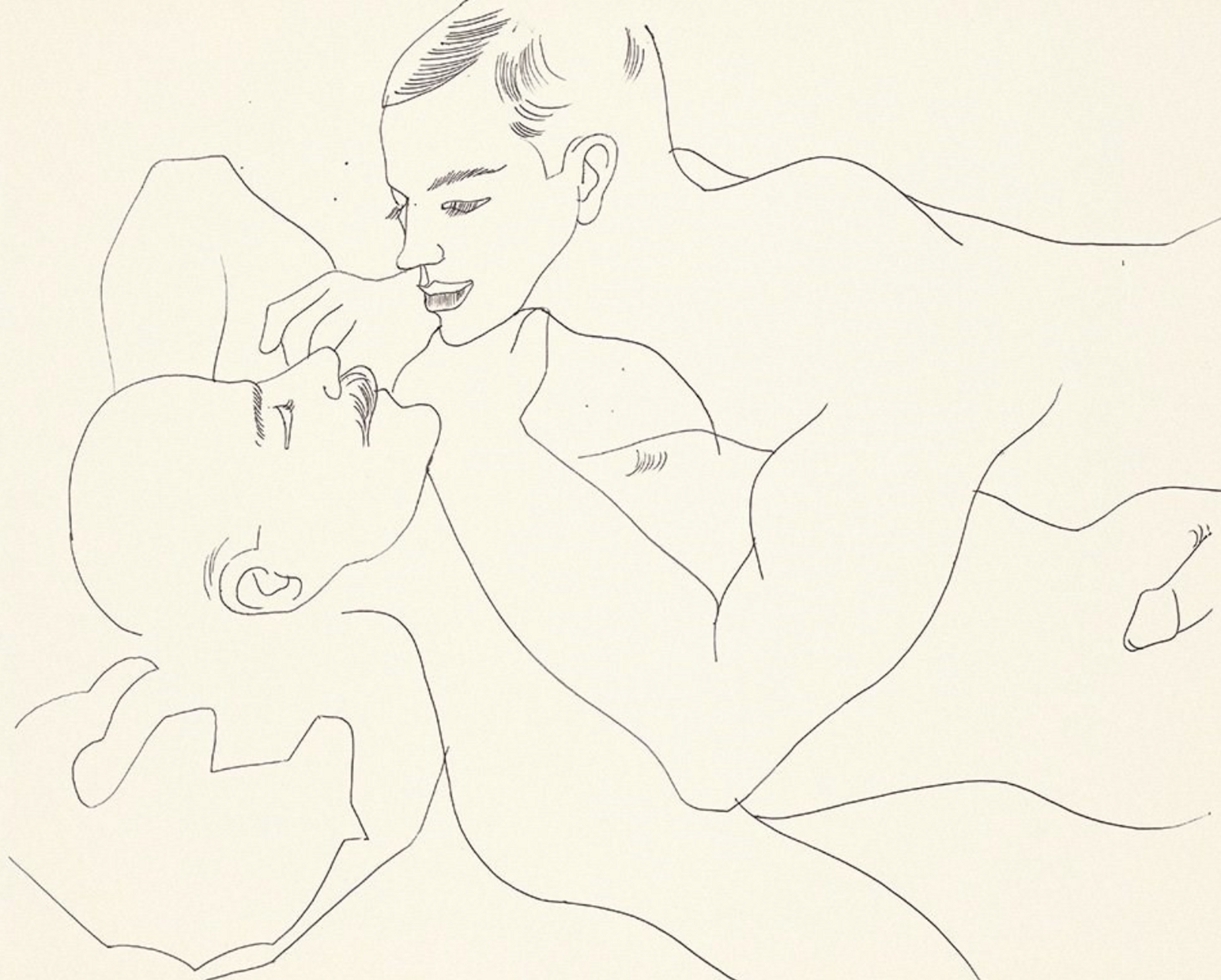

Bacon’s creative process went beyond mere replication, often blending multiple photographic sources in a collage-like manner. By integrating disparate elements, such as merging Muybridge’s dynamic human figures with Michelangelo’s classical forms, Bacon created fragmented, abstract spaces that defined much of his work. This transformative method shows that, while Bacon’s works began with photographic inspiration, his use of these images was both deliberate and deeply personal, elevating them into something entirely his own.

Matthias Grünewald: The Emotional Power of Religious Imagery

Bacon’s fascination with violence and suffering can also be traced to the intense religious imagery of Matthias Grünewald, particularly his The Isenheim Altarpiece (c.1515). The altarpiece’s vivid depictions of Christ’s crucifixion, filled with visceral agony and dramatic contrasts of light and colour, resonated deeply with Bacon. He was drawn to Grünewald's ability to use religious iconography not as a symbol of salvation, but as a stark representation of human suffering.

Bacon’s crucifixions, however, depart from Grünewald’s religious context, transforming them into existential meditations on pain, death, and the human condition. His Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), reflect his engagement with Grünewald’s emotional intensity, but Bacon transforms the traditional religious subject into an abstract, existential symbol, stripping away its spiritual connotations to focus solely on the agony and vulnerability of the human condition. Grünewald’s altarpiece, with its grotesque and tortured figures, provided Bacon with a powerful model for his own depiction of the human body in states of extreme duress.

Rembrandt: The Exploration of Psychological Portraiture

The Dutch master Rembrandt (1606–1669), one of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age, was another key figure in Bacon’s artistic development. Though Bacon was unmoved by Rembrandt’s large-scale works like The Night Watch, he was deeply moved by his intimate, psychological portraits, particularly his late self-portraits, such as Self-Portrait with Beret And Turned-Up Collar (1659). These works captivated Bacon because of their ability to convey a depth of emotion with minimal, abstract brushstrokes, and Bacon’s Self-Portrait (1971) shares Rembrandt’s focus on the passage of time and the frailty of human existence through a distorted and emotionally charged lens. Bacon, like Rembrandt, used portraiture not simply to represent physical appearances, but to explore the inner turmoil and vulnerability of the self.

Rembrandt’s influence also extends to Bacon’s technique, particularly his use of thick impasto and his approach to rendering the human face with seemingly non-figurative marks. Bacon once said of Rembrandt’s work, “The mystery of fact is conveyed by an image being made out of non-rational marks,” a principle Bacon embraced as he sought to balance abstraction and representation in his own portraits.

The influences that shaped Bacon’s art were as diverse as they were profound. From the distorted forms of Picasso, to the dynamic motion of Muybridge’s photography, these inspirations collectively influenced Bacon to forge his unique style. However, rather than simply emulating these masters, Bacon fused their techniques and ideas into something entirely his own. Through his use of abstraction, distortion, and raw emotion, Bacon redefined modern portraiture, creating powerful works that continue to resonate with their brutal honesty and emotional depth. His paintings stand as a testament to his ability to transform the influence of others into a deeply personal and innovative body of work.