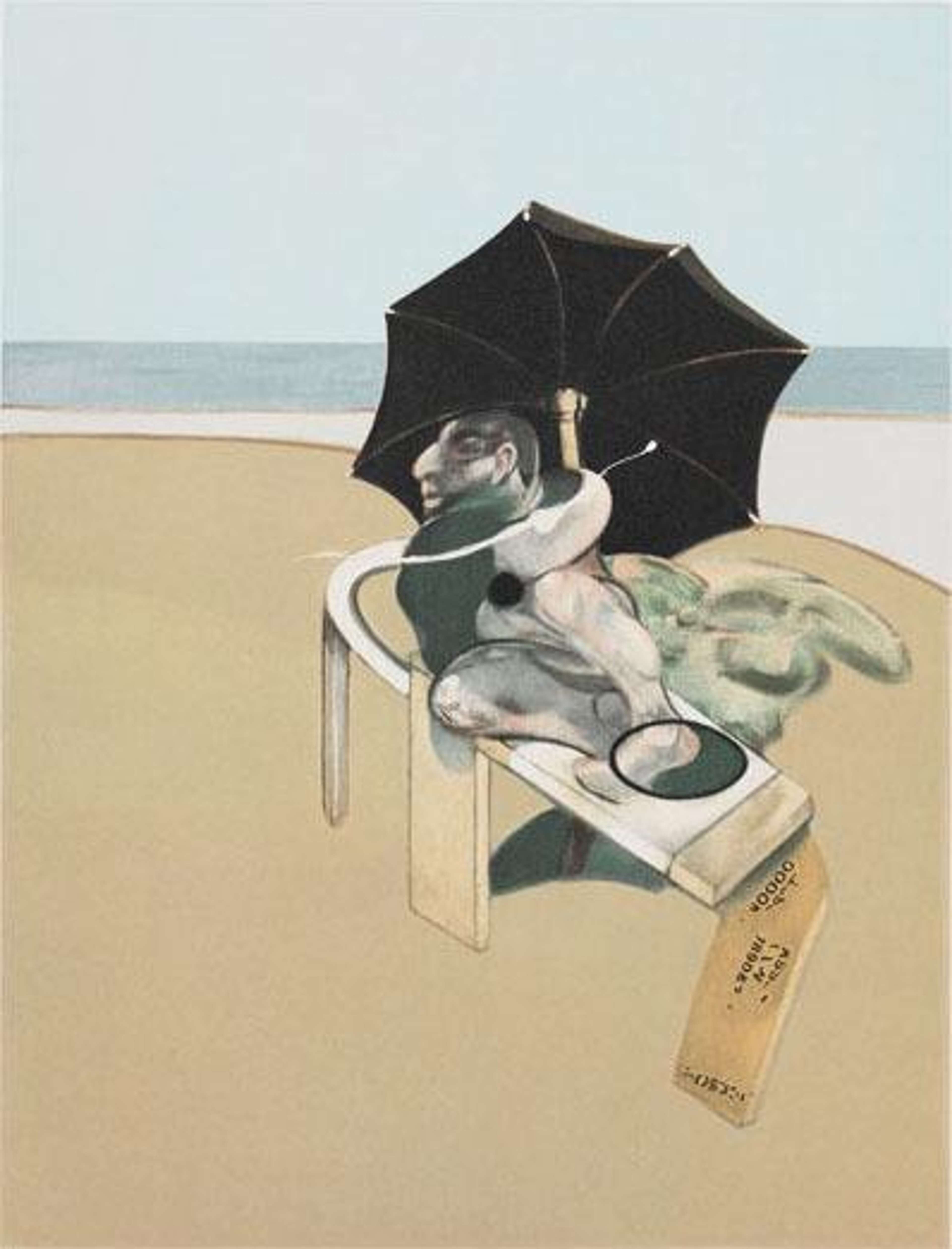

The Metropolitan Triptych (right panel) © Francis Bacon 1944

The Metropolitan Triptych (right panel) © Francis Bacon 1944 Market Reports

Key Takeaways

Francis Bacon’s 5 most famous artworks reveal his profound exploration of human suffering, mortality, and identity through disturbing, emotionally charged depictions of the human form. His unique style, often inspired by existential themes and post-war disillusionment, delves into themes of violence, power, and the fluidity of identity, cementing his place as a pioneering force in modern art.

Francis Bacon, widely regarded as one of the most important painters of the 20th century, is celebrated for his bold, emotionally charged, and often disturbing works. His art, filled with haunting distortions and raw human emotion, captures the turmoil of the post-war world, and the complexities of the human psyche. Bacon’s unique ability to manipulate form and flesh across his canvases provokes deep introspection about mortality, identity, and suffering.

By exploring his five most famous artworks, we gain insight into Bacon’s dark yet compelling vision, and his profound influence on modern art:

Image © Giles Watson via flickr / Three Studies For Figures At The Base Of A Crucifixion © Francis Bacon 1944

Image © Giles Watson via flickr / Three Studies For Figures At The Base Of A Crucifixion © Francis Bacon 1944 Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944)

Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) was a pivotal moment in his career, marking the emergence of his mature style. The triptych depicts three grotesque, distorted figures that bear little resemblance to traditional depictions of human or divine beings. These twisted forms, part animal, part human, stand in sharp contrast to the serene religious imagery typically associated with the Crucifixion. Instead of evoking redemption or spiritual sacrifice, Bacon's figures suggest a more existential form of suffering, rooted in despair, violence, and isolation. Painted in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the piece reflects the trauma of the time, embodying a sense of collective grief and existential crisis. Bacon's reinterpretation of the Crucifixion was a direct challenge to traditional Christian iconography, offering a modern, secular meditation on suffering and the human condition. The triptych's raw emotional power, conveyed through distorted anatomy and searing orange backgrounds, cemented Bacon's reputation as one of the most significant postwar painters.

Image © Wiki Commons / Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X © Francis Bacon 1953

Image © Wiki Commons / Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X © Francis Bacon 1953Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953)

Bacon’s Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953) is perhaps one of his most iconic works. Inspired by Diego Velázquez’s 1650 masterpiece, Bacon’s reinterpretation transforms the majestic and authoritative figure of the pope into a haunting, tormented being. The regal calmness of Velázquez’s portrait is shattered, replaced by a screaming figure seemingly trapped within a dark, cage-like structure. Bacon’s rendition strips the pope of his divine authority, turning him into a symbol of human frailty and existential terror. The theme of the scream, present in this and other works like Figure with Meat (1954), may reflect the postwar disillusionment with traditional structures of power and religion. This painting is not just a reimagining of Velázquez’s work, but a broader commentary on the loss of authority, faith, and certainty in the modern world. The contrast between the figure’s imposing presence and its vulnerability mirrors the psychological tension Bacon sought to explore throughout his career. The claustrophobic setting and intense emotional power of this painting situate it firmly within Bacon’s larger body of work, where the human figure is stripped of dignity and portrayed as vulnerable to overwhelming, often invisible forces.

Image © Christies / Portrait of George Dyer Staring into a Mirror 1967 © Francis Bacon 1967

Image © Christies / Portrait of George Dyer Staring into a Mirror 1967 © Francis Bacon 1967Portrait of George Dyer Staring into a Mirror 1967 (1967)

In Portrait of George Dyer Staring into a Mirror 1967, Bacon delves into themes of identity, love, and loss through the depiction of his lover George Dyer. The painting captures Dyer, whose relationship with Bacon was fraught with turmoil, gazing into a mirror, but the reflection is fractured and distorted, emphasising the instability of identity and perception. Bacon was fascinated by the idea that the self is not a fixed, coherent entity but a fluid, vulnerable state constantly shifting under the weight of emotions and external forces. The use of the mirror as a symbol reinforces this theme, as it offers a reflection not of reality, but of the mind’s perception, often distorted by fear and the passage of time. The work is also a deeply personal reflection on Bacon’s feelings for Dyer, highlighting the emotional complexities of their relationship. This painting presages the intense series of works Bacon would produce after Dyer's death in 1971, including Triptych August 1972, where grief and guilt are manifested through dark, haunting imagery. In the broader context of Bacon's oeuvre, the mirror also echoes the way Bacon examines the self in his later self-portraits, underscoring the relentless dissolution of identity under the weight of personal and existential crises.

Image © flickr / Study for a Self-Portrait - Triptych, 1985-86 © Francis Bacon 1985-6

Image © flickr / Study for a Self-Portrait - Triptych, 1985-86 © Francis Bacon 1985-6Study for a Self-Portrait - Triptych, (1985-86)

Study for a Self-Portrait - Triptych, 1985-86 Bacon turns his gaze inward, using the triptych format to explore the fragmentation of his own identity as he nears the end of his life. The triptych format, which Bacon often used for significant works, allows the viewer to see multiple facets of his ageing face, disjointed and fragmented, as if decaying in front of our eyes. The distorted features suggest a man grappling with his own physical and emotional decline, confronting the inevitability of death. Bacon’s face appears ghostly, as though it is in a state of constant flux, representing not just the ageing process but also the impermanence of identity. As with his other self-portraits, Bacon is unflinching in his portrayal of himself, choosing to depict the reality of physical decline rather than idealising his image. This work situates itself within Bacon's larger oeuvre as a meditation on the impermanence of life and the fluidity of identity, echoing the themes of instability and fragmentation present in his portraits of others, such as Dyer.

Study for Bullfight (1969)

Study for Bullfight (1969) exemplifies Bacon’s fascination with violence, power dynamics, and the primal instincts that drive human and animal behaviour. The bullfight, with its brutal choreography of life and death, becomes for Bacon a metaphor for the human condition. In this painting, Bacon captures the raw energy and violence of the spectacle, portraying both the matador and the bull as swirling, indistinct forms engaged in a fatal dance. This subject matter reflects Bacon's broader interest in the violent, animalistic side of human nature, a theme evident in earlier works such as Two Figures (1953), where human figures are shown in a primal, almost savage embrace. The bullfight, much like Bacon’s depictions of screaming popes or crucifixion scenes, is a battleground where life, death, and suffering converge, stripped of all veneer or civility. The chaotic, swirling brushstrokes and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow in Study for Bullfight also mirror Bacon's approach to flesh and space, where figures are often caught in dynamic, visceral moments of tension. This work is emblematic of Bacon’s ongoing exploration of the frailty of life and the inevitability of death, placing it firmly within his overarching preoccupation with the darker aspects of existence.