Rose Rose © Bridget Riley 2011

Rose Rose © Bridget Riley 2011

Bridget Riley

111 works

Modernist icon Bridget Riley embarked on a transformative journey through Egypt in late 1980, forever altering the trajectory of her work and leading to a revolution in her use of colour and shade. The vivid landscapes and ancient hues of Egypt inspired a bold new palette in her art and a shift into vibrant stripes. Adopting oil paints for their rich saturation, Riley redefined her approach to abstraction as a result. Her Egyptian-inspired series marked a significant phase in her career and, through exhibitions and acquisitions, Riley's work continues to resonate – bridging cultures and epochs with its visual language.

Early Influences and Formative Years in Bridget Riley’s Life

Riley, born on April 24, 1931, in London, is one of the most prominent figures in the Op Art movement, known for her dazzling and dynamic abstract paintings. Her formative years were marked by World War II, which led to the displacement of her family to Cornwall and exposed her to a variety of landscapes and environments. These later influenced her understanding of space and form. After being educated at Cheltenham Ladies' College, Riley attended Goldsmiths College and later the Royal College of Art, where she was immersed in a traditional art education, –focusing on drawing from life and studying the works of the Old Masters.

During her studies, Riley was influenced by a range of artistic movements and figures. She admired the post-impressionists and the early 20th-century avant-garde, particularly the work of Georges Seurat. Seurat's pointillism had a profound impact on her, teaching her the power of colour interaction and the eye's role in mixing shades from a distance. This fascination with visual perception and the optical effects of colour combinations became a cornerstone of her later work. Another significant influence was the abstract expressionist movement, particularly the work of Jackson Pollock, who she says “made a very powerful impact on me because it became clear that modern art was alive and I had something to react to.”

Riley's early work was figurative, but she soon began experimenting with abstraction, a transition partly influenced by her personal explorations but in line with wider trends in contemporary art during the 1950s and 1960s. Her shift towards abstraction was also a response to her dissatisfaction with the limitations of representational painting, as she sought to create art that directly engaged the viewer's perceptions and emotions without the intermediary of recognisable subject matter.

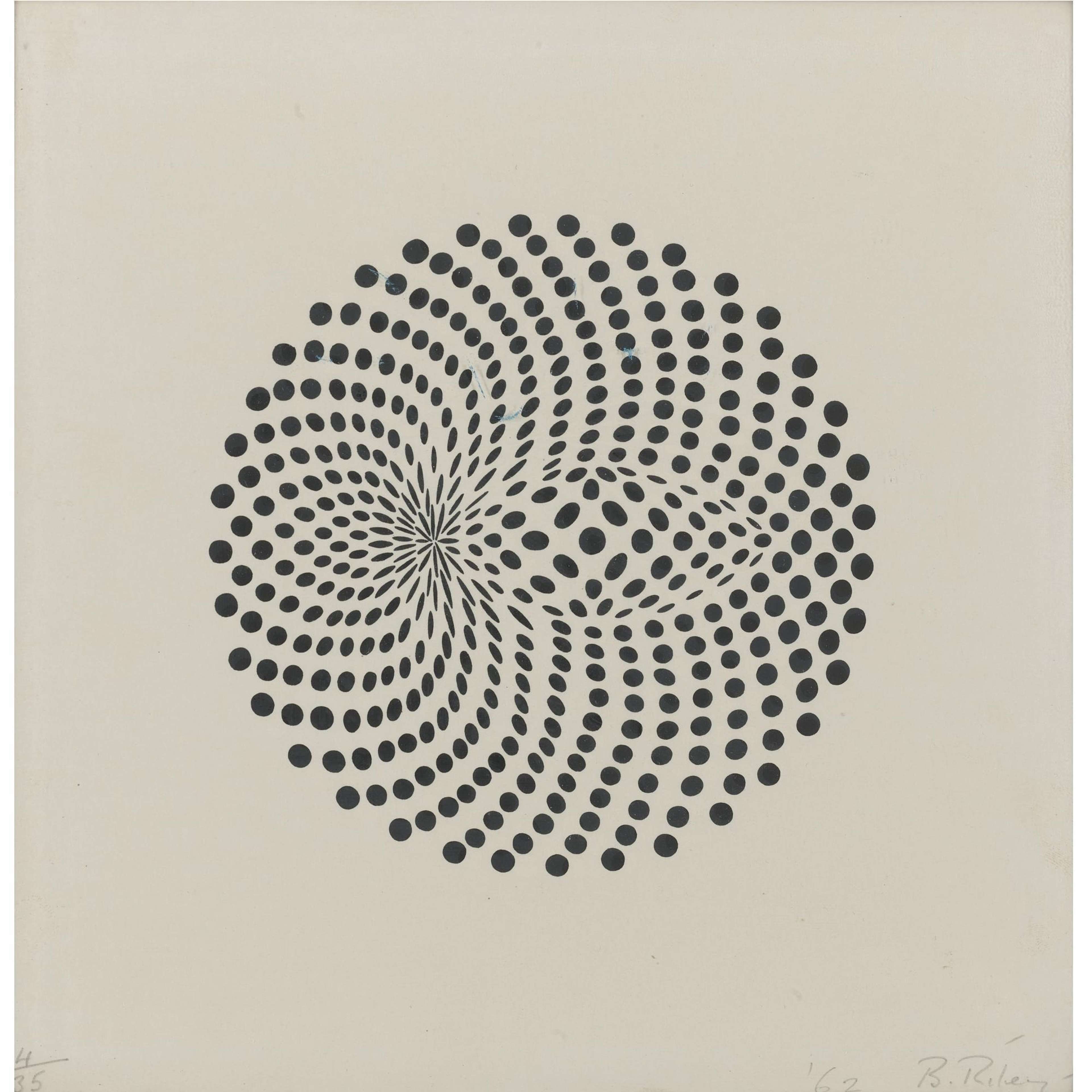

Riley and the Advent of Op Art: Mastering Monochrome

By the early 1960s, Riley had begun to develop her signature style, focusing on geometric forms, lines and colour to create optical sensations. Her black-and-white works from this period, which play with the viewer's visual perceptions, marked her emergence as a key figure in Op Art. Short for Optical Art, this movement is characterised by its use of optical illusions and abstract patterns to evoke dynamic visual effects. Riley's exploration into this realm marked a significant phase in her career, after her initial period of experimenting with figurative painting and then moving towards abstraction. She began to focus on the stark contrasts and visual impact of greyscale compositions. This shift was partly inspired by her desire to explore the fundamental aspects of sight and the ways in which simple geometric forms could be arranged to create sensations of movement and colour, even in their absence. One of Riley's most famous early works, Movement In Squares from 1961, exemplifies this phase. The painting consists of a sequence of black and white squares that seem to bend and ripple, engaging the viewer's eye in a dynamic interplay. This piece showcases Riley's dexterity in using geometric precision to elicit optical vibrations and illusions of depth and motion.

Riley's monochrome works quickly garnered attention, both in the United Kingdom and internationally. Her participation in the seminal exhibition The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1965 catapulted her and the Op Art movement to the forefront of contemporary art. In 1968, she became the first woman to receive the International Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale, cementing her status in the contemporary world.

Ancient Inspirations: Riley’s Encounter with Egypt’s Vibrant Landscapes

Her practice was significantly influenced by a visit to Egypt in 1980-81, deepening her engagement with colour and influencing the evolution of her work. Riley's trip – which took her from Cairo to Luxor, tracing the Nile River's flow through the heart of Egypt – was not just a geographical journey but also a temporal one. This route exposed her to the remnants of ancient Egypt, and the experience of travelling upriver allowed her to immerse herself in the landscape that had inspired countless generations of artists and scholars before her. This path had previously been trodden by British artists of the 19th century, who brought back to Europe an imaginative vision of it as a land of timeless beauty, deeply influencing Western perceptions of Egyptian culture.

The country's landscapes, culture, and the pervasive presence of vibrant colours in mundane and sacred contexts captivated her. Egypt's ancient civilisation, with its profound emphasis on the worship of life and fertility, presented a palette that was rich and symbolic. The ubiquity of colour seen in the natural environment, the architectural decoration, and the artefacts preserved in tombs and temples offered Riley a new lens through which to consider the application of colour in her own work. At the same time, Riley’s art does not seek to represent the culture and history of Egypt or any specific landscape directly; it is an abstraction intended to convey similar feelings without any representational fidelity.

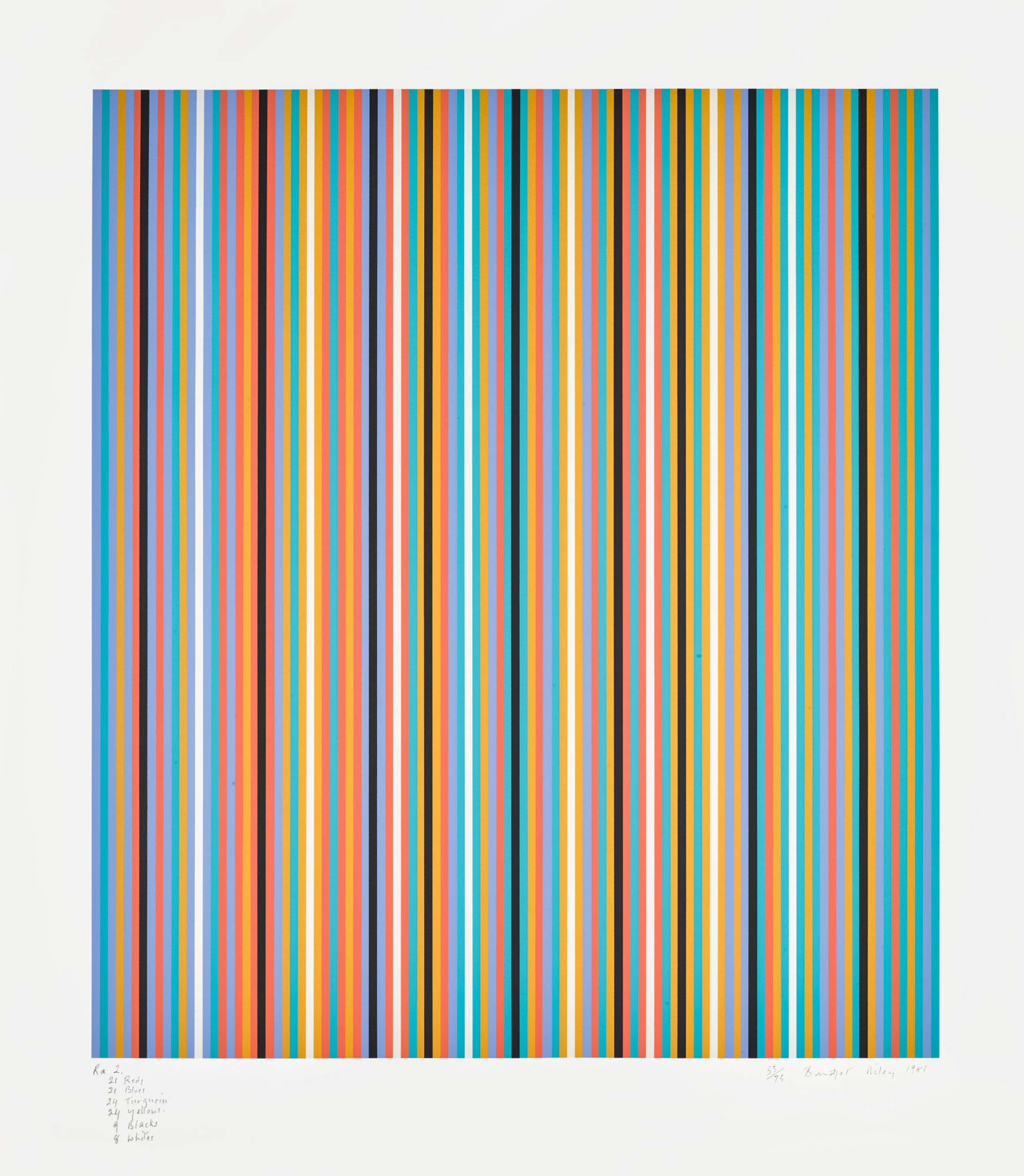

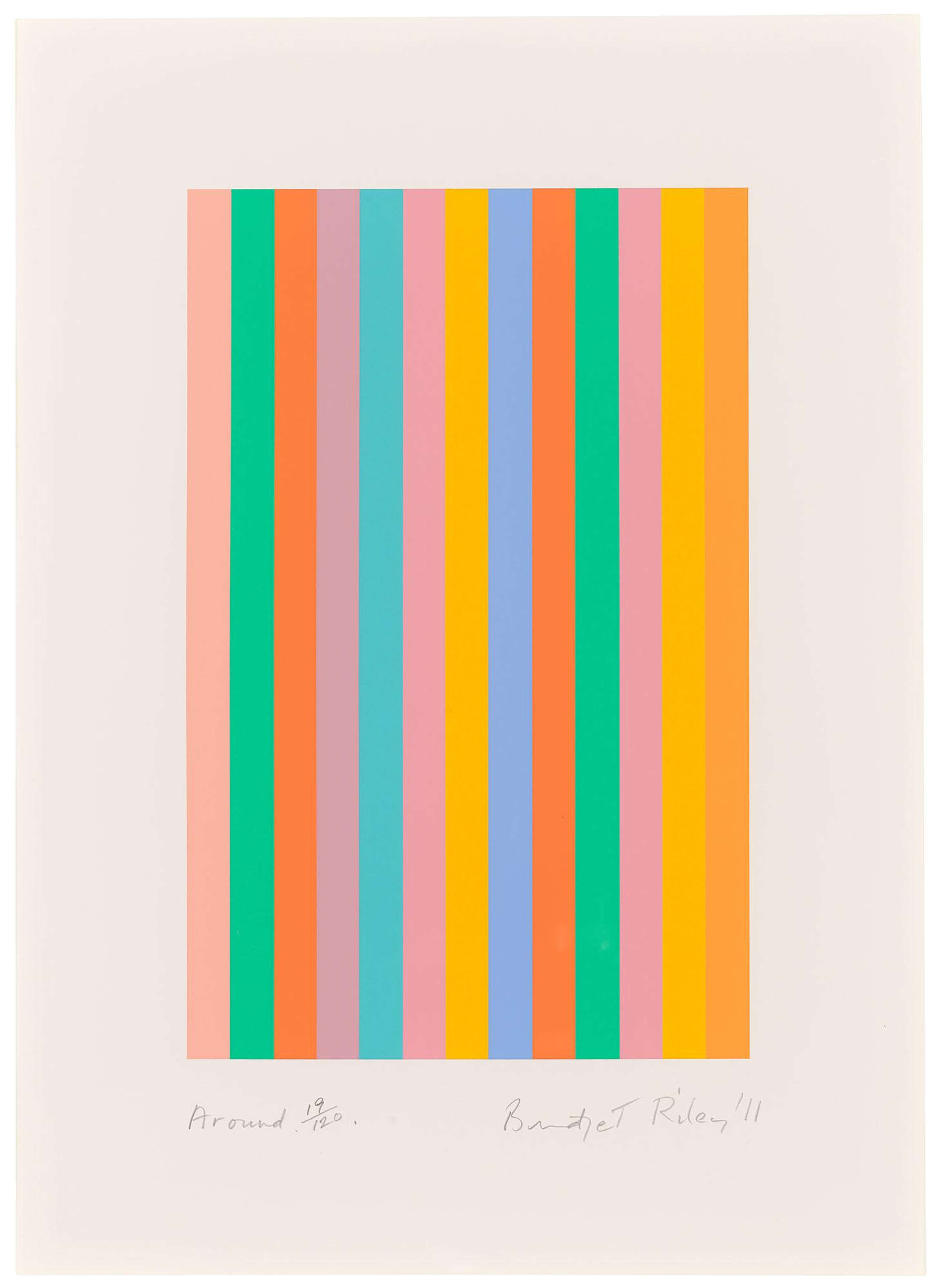

A New Chapter: Bridget Riley’s Colour Revolution After Egypt

Upon her return to London, Riley began producing a series of paintings that consistently used four or five colours: brick red, yellow ochre, blue, turquoise, and occasionally green. The first works were Ra and Ka. These hues were recreated from memory, inspired by those used in ancient Egypt, and allowed Riley to capture the essence of her personal experiences and observations in her travels. This choice of palette was reflective of her intention to infuse her work with the vibrancy and cohesion she encountered. A significant technical shift also accompanied Riley's new colour explorations and she began to favour oil paint over acrylic, drawn to its capacity for greater hue saturation. This transition allowed Riley to achieve a richness and depth in her stripes, and the use of oil paint marked a return to a more traditional medium. The introduction of the Egyptian-inspired palette facilitated a structural transformation in Riley's work. She moved away from the curves that had dominated her paintings for the previous six years, adopting instead a more formal and structured approach with vertical stripes. This change was not merely stylistic but also conceptual, as the stripes provided a new framework for exploring the interaction of hues and the optical effects that could arise from their precise arrangement.

Riley's exploration of the Egyptian palette was immediately appreciated, as evidenced by the Working with Colour exhibition, organised by the Arts Council in 1984. This featured a selection of Riley's stripe paintings alongside preparatory studies, including a large cartoon for the painting Ra. The impact of Riley's Egyptian connection extended beyond the immediate aftermath of her visit, continuing to resonate: in 1998, the UK Government Art Collection acquired Reflection for display in the British Ambassador’s residence in Cairo, bringing Riley's Egyptian-inspired work back to its nominal source.

Riley Today: Continuing Exploration and Innovation

The influence of Egypt on Riley's work is a testament to the power of cultural exchange and the enduring fascination with ancient civilisations. Her encounter with Egypt's landscapes and traditions enriched her artistic vocabulary, allowing her to push the boundaries of her practice further. This period in Riley's career underscores the importance of place and history in shaping artistic innovation, revealing how ancient inspirations can inform modern visions. She has used the palette often in her murals and commissions, and it remains popular, as evidenced by the fact that she used the Egyptian palette to create a work for the barrel-vaulted ceiling of the British School of Rome in 2023.

The palette that Riley created during her trip to Egypt continues to play a significant role in her work. The colours of Egypt—its skies, its Nile waters, the stones of its monuments, and the paintings adorning ancient tombs—inspired her to adopt a more vibrant approach in her work. Her paintings began to embody not just the visual tricks that had defined Op Art but also a deeper engagement with the emotional and cultural resonances of colour.