Dreamscapes and Nightmares: The Visual Language of Surrealist Cinema

Image © Omer Cédric Ziv/ An Andalusian Man © Un Chien andalou 1929

Image © Omer Cédric Ziv/ An Andalusian Man © Un Chien andalou 1929Live TradingFloor

Key Takeaways

The essence of surrealist cinema lies in its ability to challenge the audience’s perception of reality and art itself. Whether through the shocking imagery of Un Chien Andalou, the scathing critique of societal norms in L’Âge d’Or, or the psychological depth of the Spellbound dream sequence, surrealist films invite viewers to confront their subconscious fears and desires. By rejecting logical representation and embracing irrationality, these films offer a powerful critique of traditional values and artistic conventions.

Surrealist cinema emerged in the early 20th century as a radical artistic movement that sought to dismantle conventional storytelling and explore the depths of the subconscious. By blending provocative imagery with dreamlike narratives, surrealist filmmakers created works that subverted traditional visual language and societal norms.

Among the most influential contributors to this movement were Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, whose films - including Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L’Âge d’Or (1930) - redefined the boundaries of cinematic art. Additionally, Dalí’s collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock for the dream sequence in Spellbound (1945) demonstrated the adaptability of surrealism within mainstream cinema. These three works reveal the innovative and transgressive nature of surrealist film, and its ability to leave a lasting impact on both art and culture.

Un Chien Andalou: The Shock of the Surreal

Buñuel and Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) stands as a seminal work in surrealist cinema, conceived with the express intent of undermining the conventions of narrative filmmaking and visual coherence. Described by Buñuel as an “anti-film”, its goal was to provoke and destabilise, forcing the viewer into a space of discomfort and reflection. Its shocking opening sequence - a razor slicing through a woman’s eye - establishes the film's ethos of transgression. This act, both brutally literal and charged with metaphorical weight, functions as a deliberate violation of the viewer's passive engagement. It dismantles the perceived authority of sight, the cornerstone of cinematic language, and compels the audience to question their own interpretive frameworks.

The film’s rejection of traditional storytelling structures is not arbitrary but deeply rooted in the principles of surrealism, particularly its embrace of Freudian psychoanalysis and dream logic. Buñuel and Dalí draw heavily on Freud's theories of the subconscious, exploring taboo desires, repressed fears, and the latent content of dreams. For instance, the unsettling image of ants crawling out of a man’s hand evokes associations with decay, sexuality, and primal anxiety, creating a visceral response that bypasses rational analysis. Similarly, the iconic juxtaposition of a woman’s armpit dissolving into a sea urchin destabilises the viewer’s expectations, turning mundane corporeal imagery into something alien and disorienting. These sequences exemplify the surrealist aim of rendering the familiar unfamiliar, thereby challenging the viewer’s relationship to reality. The film’s interplay of eroticism and violence further amplifies its psychological and symbolic complexity. Sexual desire and bodily harm are intertwined, reflecting a fascination with the tension between attraction and repulsion. This thematic duality is most evident in the recurring motifs of dismemberment and penetration, whether it is the slicing of the eye, the severed hand, or the recurring phallic symbols embedded in the film’s mise-en-scène. Such imagery taps into deeply rooted anxieties about vulnerability, power, and repression, embodying Freud’s concepts of the return of the repressed.

What makes Un Chien Andalou particularly compelling is its refusal to offer definitive meaning or resolution. Buñuel and Dalí systematically avoided creating scenes that could be logically connected, rejecting causality in favour of associative leaps that mimic the disjointed structure of dreams. As a result, the film resists interpretation, leaving audiences suspended in a state of perpetual ambiguity. This deliberate obfuscation aligns with André Breton’s notion of surrealism as a revolt against rationality, an artistic act of liberation that seeks to free the mind from the constraints of logic and societal norms. Despite its anarchic structure and shocking content, Un Chien Andalou has remained a touchstone for avant-garde cinema. Its impact transcends its initial reception, where it was both celebrated and reviled, positioning it as a groundbreaking critique of both filmic convention and the broader cultural assumptions of its time. By dismantling the viewer’s expectations and interrogating the power of cinematic representation, Un Chien Andalou not only embodies the ethos of surrealism but also challenges the boundaries of what cinema can achieve as an art form.

L’Âge d’Or: Scandal and Subversion

Building upon the provocative foundation of Un Chien Andalou, Buñuel and Dalí reunited in 1930 to craft L’Âge d’Or, a feature-length film that intensified their assault on societal conventions. Where Un Chien Andalou was an abstract exploration of subconscious desires and fears, L’Âge d’Or sharpened its focus into a more pointed critique of bourgeois hypocrisy, religious orthodoxy, and repressive social structures. The result was a film that not only scandalised its contemporary audience, but also expanded the possibilities of cinema as a tool for subversion and rebellion.

From its opening moments, L’Âge d’Or positions itself as a radical departure from traditional filmmaking. The film begins with a pseudo-documentary on scorpions - a seemingly irrelevant prelude that sets the tone for its episodic and fragmented narrative structure. The plot ostensibly revolves around a pair of lovers opposed by societal and religious constraints. Yet this thin narrative thread is repeatedly interrupted by surreal vignettes and disjointed sequences that defy linearity and coherence. These narrative disruptions are not mere experiments in form but deliberate acts of disorientation, forcing the viewer to experience the film intellectually and emotionally, rather than passively absorbing it.

Unlike its silent predecessor, L’Âge d’Or incorporates sound, but in ways that are far from conventional. Dialogue is sparse and often disjointed, serving more as a disruptive element than a narrative tool. This use of sound enhances the surreal quality of the film, creating a fractured reality where time, space, and logic collapse. Buñuel employs this auditory dissonance alongside his visual provocations, such as the banquet scene where a “genteel” gathering devolves into chaos, with guests behaving in ways that grotesquely parody bourgeois decorum. These moments of absurdity expose the veneer of respectability that masks deeper hypocrisies and base instincts within society. Perhaps the most controversial aspect of L’Âge d’Or is its explicit critique of religious institutions. The climactic sequence, a nod to the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, reimagines Jesus as a libertine presiding over orgiastic debauchery. This irreverent blending of sacred and profane imagery was met with immediate outrage, leading to the film’s banning in multiple countries and its temporary suppression by religious and political authorities. L’Âge d’Or remains a landmark in the history of avant-garde cinema; its unflinching examination of societal taboos and its willingness to provoke, unsettle, and offend exemplify the radical potential of film as an art form.

The Dream Sequence in Spellbound: Dalí’s Vision for Spellbound

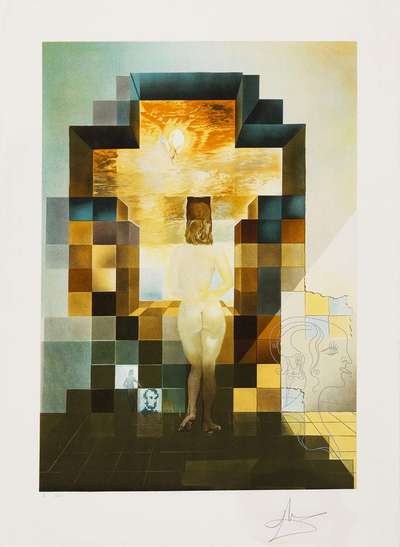

Dalí’s collaboration with Hitchcock on the dream sequence in Spellbound (1945) represents a moment in cinematic history, where the avant-garde sensibilities of surrealism infiltrated Hollywood. Tasked with illustrating the protagonist’s subconscious mind, Dalí brought his trademark visual style to a psychological thriller that was deeply embedded in the language of psychoanalysis. This collaboration not only elevated the narrative complexity of Spellbound, but also demonstrated how surrealist principles could be adapted to mainstream cinema without losing their provocative edge. Dalí’s contribution to the sequence is immediately striking - instead of relying on soft-focus techniques and ambiguous symbolism, Dalí employed a hyperreal aesthetic that imbues the sequence with a visceral intensity. His designs feature enormous blank playing cards, distorted landscapes, emerging figures, all-seeing eyes and distorted wheels, all rendered with sharp precision that capture the disintegration of the protagonist’s psyche as he grapples with repressed memories.

The collaboration reflects Hitchcock’s fascination with the mechanisms of memory and repression. The narrative of Spellbound revolves around psychoanalysis, a theme that aligns naturally with Dalí’s surrealist focus on the subconscious. The dream sequence becomes a crucial narrative device, providing visual clues that ultimately unravel the mystery at the film’s core. Dalí’s surrealist imagery operates on multiple levels, serving both as an exploration of the protagonist’s internal conflicts and as a symbolic commentary on the fragility of perception and the instability of reality.

Despite Dalí’s ambitious vision, the sequence was truncated from its original length due to studio constraints and concerns over pacing, however even in its abbreviated form, Dalí’s work retains its transformative power. The sharp juxtaposition of his avant-garde aesthetic with the film’s otherwise conventionality creates a moment of profound disorientation for the viewer, mirroring the protagonist’s psychological turmoil. The sequence also serves as a bridge between two seemingly disparate artistic realms: the subversive ethos of surrealism and the commercial demands of Hollywood. While Dalí’s earlier works, such as Un Chien Andalou and L’Âge d’Or, were designed to shock and destabilise audiences, his work in Spellbound demonstrates a capacity to integrate surrealist imagery into a cohesive narrative framework.

The Legacy of Surrealist Cinema

The works of Buñuel and Dalí exemplify the enduring power of surrealist cinema to challenge perceptions and provoke thought. Un Chien Andalou and L’Âge d’Or dismantled traditional storytelling through radical imagery and irreverent critiques of societal norms, while the Spellbound dream sequence demonstrated surrealism’s potential within commercial frameworks. Together, these films showcase the transformative capacity of surrealist art, blending pleasure and revolt to create a visual language that transcends time. At its core, surrealist cinema challenges viewers to confront the subconscious, dismantling the illusions of stability and rationality that underpin both art and society. The shocking imagery, fragmented narratives, and symbolic depth found in these films transcend visual spectacle, compelling audiences to grapple with their own fears, desires, and cultural assumptions.