Mao

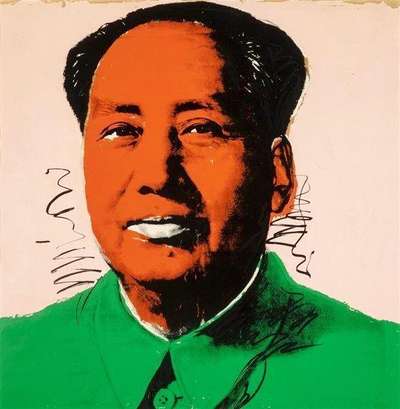

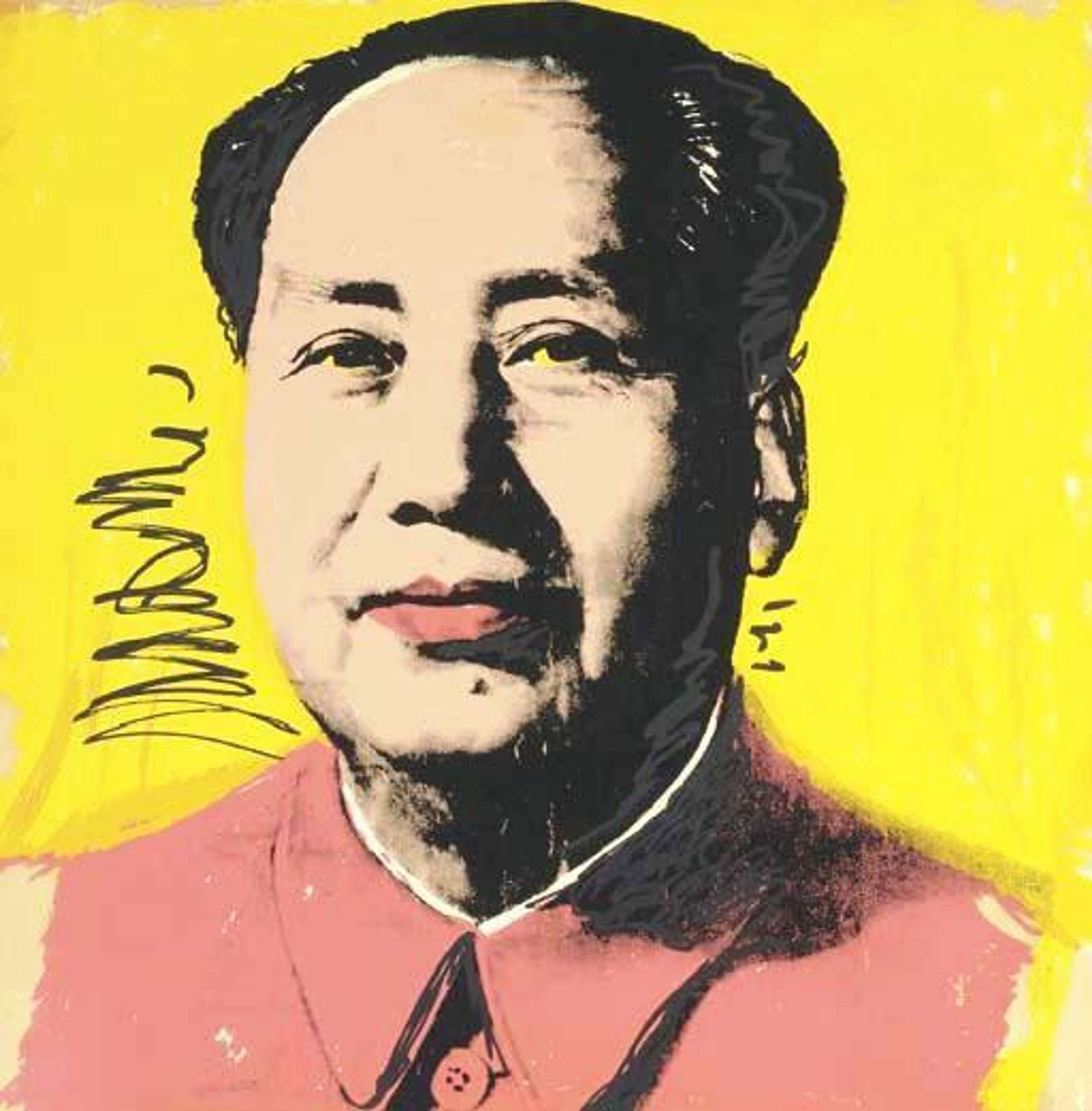

Andy Warhol began his Mao series in 1972, the year of President Nixon’s momentous diplomatic visit to China. He inflects his interest in celebrity with a timely new political note, prompted by the mass reproduction of the original Mao portrait across China, as a form of Communist propaganda.

Andy Warhol Mao For sale

Mao Value (5 Years)

Works from the Mao series by Andy Warhol have a strong market value presence, with 512 auction appearances. Top performing works have achieved standout auction results, with peak hammer prices of £817420. Over the past 12 months, average values across the series have ranged from £1153 to £91739. The series shows an average annual growth rate of 8.9%.

Mao Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mao (F. & S. II.97) Andy Warhol Signed Print | 9 Dec 2025 | Bonhams New Bond Street | £25,500 | £30,000 | £40,000 |

Mao (F. & S. II.94) Andy Warhol Signed Print | 3 Dec 2025 | Dorotheum, Vienna | £21,250 | £25,000 | £35,000 |

Mao (F. & S. II.92) Andy Warhol Signed Print | 3 Dec 2025 | Dorotheum, Vienna | £21,250 | £25,000 | £35,000 |

Mao (F. & S. II.95) | 3 Dec 2025 | Dorotheum, Vienna | £21,250 | £25,000 | £35,000 |

Mao (F. & S. II.96) Andy Warhol Signed Print | 19 Nov 2025 | Doyle Auctioneers & Appraisers | £18,700 | £22,000 | £29,000 |

Mao (F. & S. II.98) Andy Warhol Signed Print | 19 Nov 2025 | Doyle Auctioneers & Appraisers | £16,150 | £19,000 | £25,000 |

Mao (F. & S. II.93) Andy Warhol Signed Print | 13 Nov 2025 | Swann Galleries | £18,700 | £22,000 | £30,000 |

Mao (F. & S. II.125A) | 13 Nov 2025 | Swann Galleries | £935 | £1,100 | £1,450 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

An artist defined by his obsession with fame and icons of popular culture, Warhol’s Mao series contains one of his most recognisable portraits. He was consistently drawn to the representation of figures in the public eye, from his earliest screen prints of Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe to his later representations of Vladimir Lenin. One of Warhol’s most recognisable portraits is that of the Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976). Warhol was compelled to portray Mao as he became increasingly aware of the power and ubiquity of a man who was to become one of the most recognisable figures in modern history.

Warhol’s depiction of Mao was set in motion by President Richard Nixon’s visit to China, an event which was widely publicised on the world’s media stage in its quest to end years of diplomatic isolation between the two nations. Bruno Bischofberger, Warhol’s long-time dealer and supporter in Zurich, also encouraged Warhol to return to painting by making portraits of the man he saw to be the most important figure of the 20th century. The cult of Mao pervaded the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976 with the Chairman’s image becoming the focus of political propaganda disseminated throughout China during this time. This inescapable ubiquity of Mao’s image instantly attracted Warhol, who drew comparisons with his own screen prints of iconic figures as he remarked, “I have been reading so much about China. They’re so nutty. They don’t believe in creativity. The only picture they ever have is of Mao Zedong. It’s great. It looks like a silkscreen.”

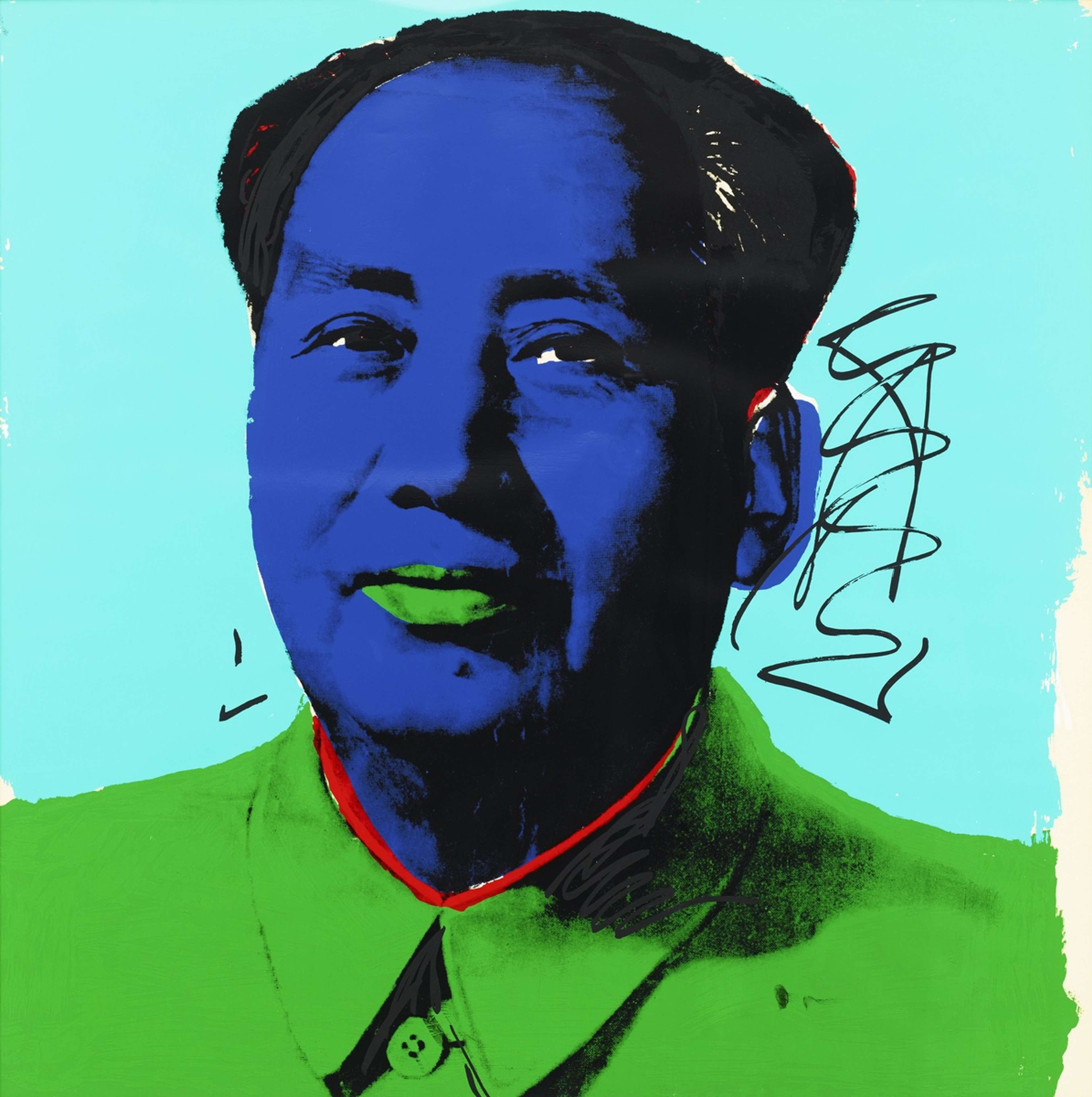

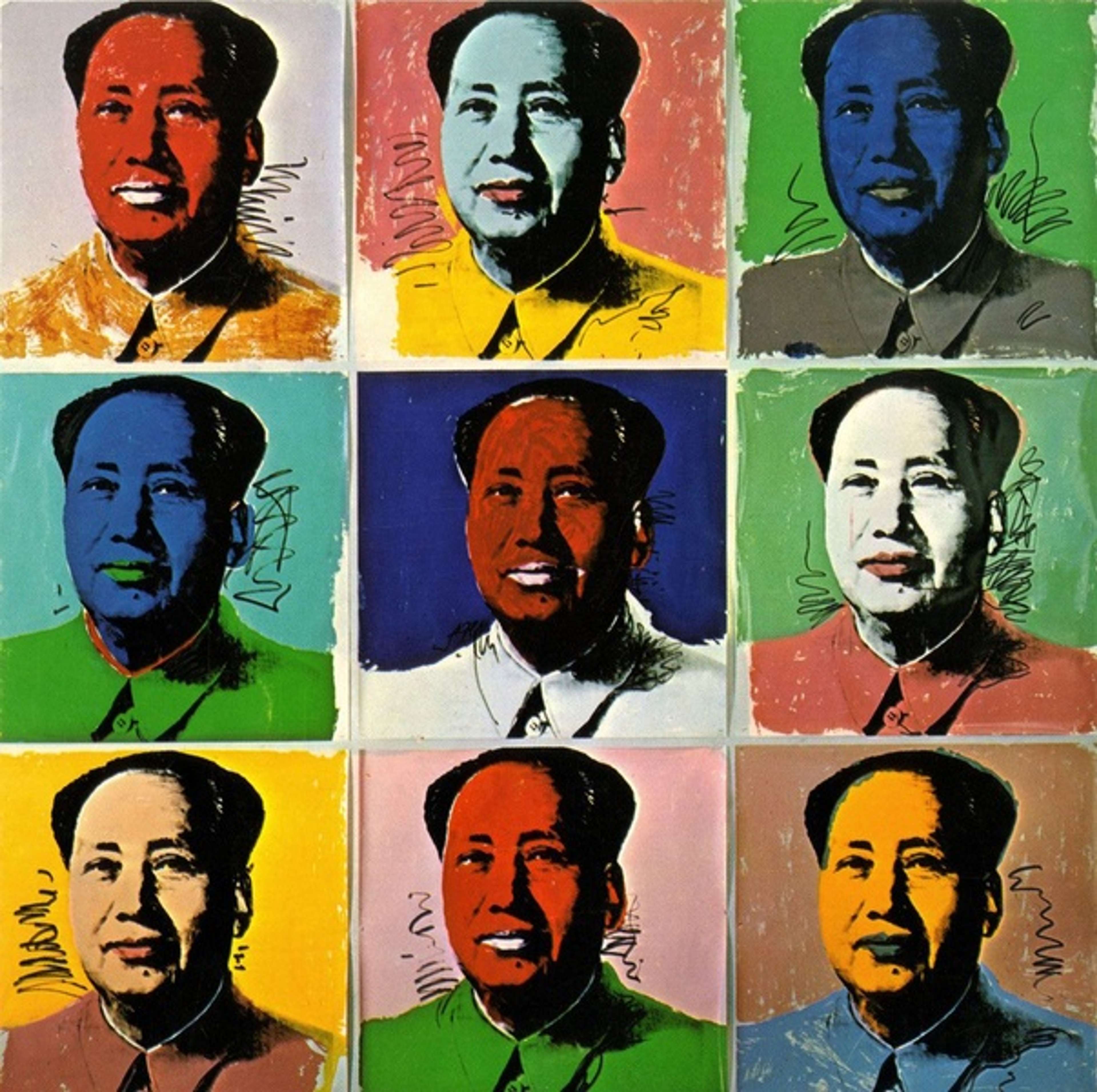

Warhol therefore chose to base his portrayal of Mao on the Communist leader’s internationally recognisable official portrait that was illustrated on the cover of the widely circulated 1966 publication Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong, also known as the Little Red Book. Between 1972 and 1973 Warhol created 199 Mao paintings in five set scales across five individual series, in addition to a series of 10 screen prints. The prints employ a broad spectrum of vivid colours that are synonymous with the printmaking technique and aesthetic of Warhol’s most renowned work. Here, Warhol explores his colour palette playfully, adding red rouge, eye shadow and flamboyant brushstrokes that compete with the photographic image, exemplified in Mao 91 and Mao 92 This act of printing and painting in multiple variations demonstrates Warhol’s experimentation with typical art processes, manipulating colour and creating contrasting effects with each repetition.

With this vibrant aesthetic Warhol draws parallels between the communist propaganda machine and American capitalist consumerism, a theme which transcends much of his work. In some instances, Mao appears to be wearing makeup, his mole darkly coloured as a beauty mark that echoes Warhol’s famous images of Marilyn Monroe. Mao becomes morphed into a glamorised 1970s pop icon, a clash of imagery that creates an interplay between controlled communist propaganda and Western fashion kitsch.

Warhol’s Mao series had a lasting influence in China following the Cultural Revolution. The Stars Art Group, a group of artists which included Ai Weiwei, would regard Warhol’s imagery of Mao as a primary point in exploring the symbols of a communist regime.