The Blueprint Drawings 5 © Keith Haring 1990

The Blueprint Drawings 5 © Keith Haring 1990

Interested in buying or selling

Keith Haring?

Keith Haring

249 works

Keith Haring is celebrated for his vibrant and dynamic style which transmitted ideals of hope, joy and unity. Renowned for his public works and activism, Haring's art became a powerful voice against societal issues, particularly during the height of the AIDS crisis. As he navigated his own personal battle with the disease, Haring's work underwent a poignant transformation, revealing deeper layers of emotional depth and introspection. His final years highlight his resilience and commitment to his art but also underscores the role of art as a medium for processing, confronting, and communicating the profound challenges of life and mortality.

Keith Haring: A Joyous Life

Haring was a uniquely vibrant figure in the art world, known for his joyous and hopeful perspective in his art and personality. His works are characterised by their lively, animated figures and bold, graphic lines, often filled with brightly optimistic colours. This signature style made his art accessible and beloved by a wide audience across all ages. Haring's art was also infused with a sense of energy and life that reflected his own personality. He was known for his infectious enthusiasm and his belief in art as a tool for communication and social change; his work often carried messages of love, peace, social justice and unity.

In the streets of New York City, Haring found his canvas. He started with chalk drawings on empty advertising panels in subway stations, public artworks that were gifts to the city—happy surprises for commuters and passersby. His art was democratic, intended to be enjoyed by people from all walks of life, regardless of their background or education. Haring worked with like-minded artists and activists, including Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, forming a vibrant community that sought to bring art into the public realm and address social issues.

Moreover, Haring's work in community service further reflected his positive impact on society: he conducted numerous workshops with children and his foundation, established before his untimely death, focused on providing funding and imagery to AIDS organisations and children’s programmes. His legacy as an artist and a person is marked by a sense of joy and hope. His ability to convey complex messages through simple, vibrant, and energetic imagery made his work not only iconic but also deeply resonant on a human level. Haring's art remains a symbol of optimism, a testament to the power of creativity in fostering positivity and change.

The Impact of Illness: How Personal Struggles Influenced Haring's Art

By the mid-1980s, however, the AIDS epidemic was already in full-swing in New York City’s artistic community. Haring, who was a prominent figure in this community and openly gay, found himself increasingly affected by the epidemic, both personally and professionally. The disease was taking a heavy toll, claiming the lives of many – including friends and colleagues. This atmosphere of loss and uncertainty deeply influenced Haring’s perspective and work. He sensed the epidemic’s closeness and inevitability, feeling it was only a matter of time before he too would be directly impacted.

Haring's fears materialised in 1987 when he was diagnosed with HIV, which developed into AIDS in 1988. The discovery of a purple lesion on his leg and difficulty in breathing were ominous signs that marked a turning point in his life and artistic journey. However, instead of fully succumbing to despair, Haring found in his diagnosis a renewed urgency and motivation; he immersed himself more intensely in his work, embarking on a frantic pace of creation that took him across the globe. In this period, Haring's art became a vehicle for activism and awareness as he painted in hospitals, orphanages, daycares, and charities. He engaged in campaigns aimed at boosting awareness and understanding of AIDS, using his art to communicate messages of solidarity, compassion and understanding.

At the same time, Haring was also grappling with his own mortality and the emotional toll of his diagnosis. This is vividly embodied in The Blueprint Drawings, a series that stands as one of his last cohesive projects. Originally conceived in 1980 and revisited in 1990 – a month before his untimely death – this series represents a poignant culmination of Haring's artistic journey, deeply influenced by his personal battle with the disease. These prints show a stark, monochrome aesthetic, reminiscent of comic strips, in which Haring’s iconic figurative motifs take on a new depth and intensity. The series is rife with images of radiating bodies, dotted landscapes and figures, UFOs, barking dogs, and explicit sexual imagery. These elements coalesce into an ambiguous narrative that delves into themes of homosexuality, otherness, disease and death. These reflect Haring's personal experiences and the broader context of the AIDS epidemic, which disproportionately affected the LGBTQ+ community and polarised the socio-political landscape of the time.

The Blueprint Drawings confront these complex themes head-on. Haring's unflinching imagery is a bold statement, a defiance against the silence and stigma that often surrounded discussions of AIDS and homosexuality. His decision to leave the prints untitled further amplifies their impact, inviting viewers to engage with the art without preconceived notions, allowing for a more honest and personal interpretation. Through this series, Haring not only confronts the personal and collective challenges posed by AIDS but also pushes the boundaries of visual storytelling, offering a raw, unadulterated glimpse into the realities of a life and a community in turmoil.

Artistic Response to Adversity: Haring's Technique and Style Shifts

At the same time, Haring’s style was also evolving. This was vividly reflected in his 1989 collaboration with writer William S. Burroughs on the series The Valley, an interplay of Haring's visuals and Burroughs' text from The Western Lands. It is a stark departure from the vibrant optimism typically associated with Haring's works and instead presents a fragmented and at times violent narrative. With its ominous overtones and apocalyptic imagery, The Valley can be seen as a reflection of Haring's internal landscape during this period, showcasing a more sombre, reflective, and at times, foreboding aspect of his artistic expression. Characterised by its exclusive use of black and white, it marks a notable contrast to many of Haring's earlier black and white pieces.

This series is distinguished by its use of fine lines and complex compositions, a departure from the bold, simplified forms that defined much of his iconic work. The intricate detailing in each print is intentional, crafted to mirror the elaborate narrative of Burroughs' text. This attention to detail and complexity in the imagery reflects a deeper engagement with the narrative content, allowing for a more nuanced and layered artistic expression. Another significant shift is the depiction of figures with discernible gender and facial features, a marked change from his famous genderless and featureless figures – suggesting a move towards a more literal and representational approach. This evolution in his portrayal of figures can be interpreted as a reflection of Haring's own grappling with identity and the human condition, themes that became increasingly pertinent as he confronted his mortality. The series stands as a powerful reminder of the transformative potential of art in the face of hardship, and of Haring's enduring legacy as an artist who bravely confronted the most challenging aspects of human experience.

The Role of Colour and Form in Expressing Haring's Inner Turmoil

Haring's White Icons series serves as an exploration into the role of colour and form in expressing inner turmoil, particularly in the context of his personal struggles during the final years of his life. This series, a reinterpretation of his Icons prints, strips away the vibrant, saturated colours characteristic of the original works, opting instead for a pure, embossed representation on white. This stylistic choice is revealing of Haring's state of mind and artistic intentions during this period. In the original Icons series Haring utilised flat, saturated colours – a nod to the rise of commercialism and mass production that marked his era. These colours brought a sense of immediacy and visual impact, aligning with the commercial aesthetics of the time and reflecting the artist's engagement with contemporary culture and its visual language. However, in White Icons, the absence of these eye-catching colours signifies a shift towards a more introspective and subdued expression.

The decision to depict his best-known symbols – the radiant baby, angel, flying devil, and barking dog – without their original vibrant hues simplifies the images, stripping them down to their core essence. This simplification results in a subtler tone, creating a different emotional resonance compared to the original series. The use of white, particularly in the context of Haring's life at the time, is especially poignant. White is often associated with peace, purity, and simplicity. In the final year of Haring's life, a period marked by personal struggle and a confrontation with mortality due to his illness, the choice of white could be interpreted as a reflection of a search for peace, a stripping away of the superfluous to focus on the essential. Moreover, the embossed forms on white create a sense of depth and texture, drawing attention to the physicality of the artwork and the act of creation itself. This tactility contrasts with the flat appearance of the original Icons series, suggesting a more personal, introspective approach.

A Contrast of Themes: Joy and Despair in Haring's Work

Haring's final works oscillate between joy and despair, as he grappled with the personal impact of AIDS. This dichotomy is vividly expressed through the continued issuance of his joyful, iconic Pop Shop prints alongside more sombre, reflective pieces. While the Pop Shop prints created during this period continued to radiate the vibrant, energetic optimism that had become a hallmark of his style—accessible, commercial, and infused with a sense of fun and whimsy— Haring was also creating works such as Unfinished Painting (1989). This particular piece, notable for its incomplete nature and dominant purple hue, speaks volumes about the impact of AIDS on both Haring's life and the broader artistic community. By leaving a significant portion of the canvas blank, Haring poignantly symbolises the unfinished lives of those lost to AIDS, including his own. The incomplete canvas becomes a metaphor for the dreams, projects, and potential cut short by the disease, reflecting a collective and personal tragedy.

This juxtaposition of joy and despair in Haring's final works highlights the complexity of his experience during this period. While he continued to engage with themes of joy, celebration, and accessibility through works like the Pop Shop prints, he also confronted the darker realities of his life and the lives of those around him, sombre reminders of the unfinished journeys and the profound sense of loss brought about by the epidemic.

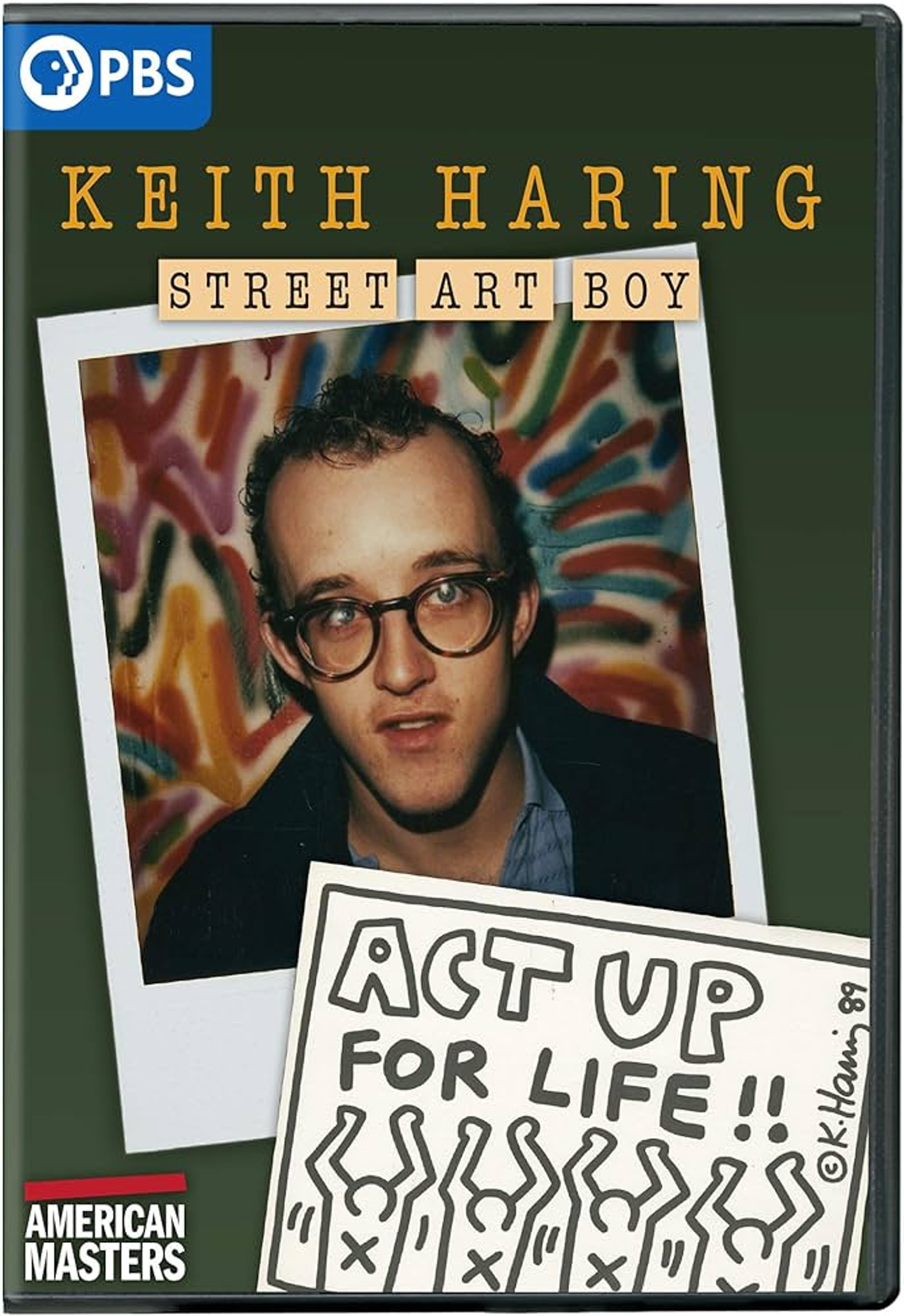

Image © CBS Keith Haring: Street Art Boy / Keith Haring's final sketch, done on his deathbed, owned by friend and artist Kenny Scharf

Image © CBS Keith Haring: Street Art Boy / Keith Haring's final sketch, done on his deathbed, owned by friend and artist Kenny ScharfThe Legacy of Keith Haring: Bridging Art, Life and Activism

Haring continued to create even as he was struggling with his own health problems. In his final sculptural work, Altarpiece – now in the collection of the Denver Art Museum – the graffiti-style figures reflect a personal religious narrative, with upward-reaching stylised figures and fallen angels. The bronze triptych encapsulates the artist's creative power and dedication, and was completed weeks before his death from AIDS on February 16, 1990. It features his signature hieroglyphic figures, blending Christian altarpieces with global religious shrines. In a race against time, Haring directly carved the design into clay without preliminary sketches, achieving the spontaneity and freedom so characteristic of his work. Posthumously cast, the first edition of Altarpiece was a monument at Haring's own memorial service in New York City. The piece pays homage to all AIDS victims, inviting contemplation on vulnerability and mortality while offering reconciliation, healing, and a vision of a future filled with love and compassion.

Today, Haring's legacy stands as a powerful testament to the fusion of art and activism which continues to resonate and inspire long after his passing. Through his vibrant art and passionate advocacy, Haring brought joy and accessibility to the art world. His relentless activism, especially in the face of the AIDS crisis, gave voice to marginalised communities and raised awareness about critical social issues. Haring's art transcended the conventional boundaries of the gallery, reaching into the streets, hospitals, and public spaces, thereby democratising the experience of art. In doing so, he showed that art can be a powerful tool for change, a means of expression not just for the artist, but for the hopes, fears, and struggles of an entire generation.