MyArtBroker Film Reviews: Keith Haring - Street Art Boy (2020)

Image © IMDB / The film poster for “Keith Haring: Street Art Boy” 2020

Image © IMDB / The film poster for “Keith Haring: Street Art Boy” 2020

Interested in buying or selling

Keith Haring?

Keith Haring

249 works

Keith Haring: Street Art Boy is a 2020 documentary film directed by Ben Anthony. This film presents the definitive story of the iconic artist Keith Haring in his own words. During the 1980s, Haring emerged as a prominent figure in the art world and popular culture, known for his distinctive and instantly recognisable style that became a hallmark of the decade. The narrative of the documentary is built around previously unheard interviews with Haring conducted following his AIDS diagnosis, and his loved ones, who provide tender and candid first-hand accounts of the artist.

Haring’s own interviews were given to writer and art critic John Gruen in 1989 for his biography, which the film blends with stunning archive footage and an edgy soundtrack, It covers Haring's journey through the galleries and nightclubs of downtown New York's art scene, his rebellious and ingenious approach, and his inspiration from the city's graffiti, where he transformed New York's subways, tarpaulins, and walls into his canvases.

Keith Haring: Street Art Boy offers an extraordinary insight into the life of an artist who lived and created with boundless energy, significantly impacting the social, cultural, and political landscapes of the 1980s until his untimely death in 1990.

The Early Years

It opens focusing on Haring’s youth, emphasising the fact that he was internationally famous before the age of 25. A poignant voiceover of Haring talking about his democratic approach to art plays over footage from his career.

Haring begins speaking about his younger years including wearing his signature glasses and being insecure as a child, often feeling isolated from other children. As opposed to sports, he was more interested in creating clubs. His parents say how Haring would always be drawing in school, especially when he was not meant to be doing so, and show a letter from when he was around the third grade: “When I grow up, I would like to be an artist in France. The reason is because I like to draw. I would get my money from the pictures I would sell. I hope I will be one. Keith Haring.”

A childhood friend mentions how they would deliver newspapers together, reading the news as they did so. He notes how Haring was an activist for as long as he knew him, and how when Nixon ran for president they scribbled on buildings using bars of soap – a foreshadowing of Haring’s chalk medium in the subways. Haring talks about doing angel dust as a young adult, with his friend who was “making it”, before getting a job at an arts centre in Pittsburgh – although he was not a student there, he used its facilities.

Haring speaks of a breakthrough moment, seeing a Pierre Alechinsky retrospective at the Carnegie in Pittsburgh: “The work was so close to what I was doing, it was the first time I felt that I was doing something that was worth something.”

Career Beginnings

In 1978, aged 20, he did his first show in New York. Haring speaks of having moved there craving “the intensity”, both in terms of the art world and of his life, although the city was a bankrupt, derelict and dangerous place at the time. Around this time, he starts coming to terms with his homosexuality.

In his early years in the city, Haring enrolled at the School of Visual Arts, where he met Kenny Scharf, who recalls meeting him for the first time: “I was in the hallway and I heard Devo music, and there’s Keith painting himself into a corner, with these black strokes, and every stroke was to every beat of the music. He had painted the entire room, he was at the very end and he was standing in the corner and he was marking his mark, and I was like ‘wow, this is the reason why I came to New York.’” Scharf notes that Haring ruled SVA at the time, and was immediately instantly recognised as a real talent.

The documentary briefly touches on Haring's time at Club 57, and how its DIY spirit was an abject rejection of the “uptown” elitism. Scharf speaks of how he and Haring were increasingly bored with the pretentious art world, which they perceived as trying too hard. Haring speaks about becoming obsessed with “why” he is an artist, and fascinated with the streets of New York – particularly graffiti in the subway and its “incredible calligraphy”, to which he “felt an incredible affinity”, a “pop cartoon sensibility of kids who had grown up with cartoons in technicolour.”

In 1980, Haring participated in the Times Square Show, which was the first time the art world acknowledged that this underground culture existed. A few days or weeks after that, Haring began drawing his iconic flying saucers and animal figures: “They were really roughly, roughly, roughly drawn because I hadn’t done anything figurative in a really long time, and out of these were born the entire vocabulary that came afterward. All of a sudden it totally dawned on me, ‘What am I doing in school?’ I had discovered my own work, so I decided I was going to have a show.”

Meteoric Rise

In 1981, Haring showed at PS 122 - he had been given the space for one month, but it became incredibly buzzworthy. Around this time, Haring showed his art to the gallery owner Tony Shafrazi, who he respected for his protest art against Picasso’s Guernica – even though Haring was a big fan of the work.

He began doing graffiti on the streets, further developing the “dog” and “baby” motif. The documentary states Haring did not want to use spray paint for the fear of overshadowing or appropriating from the works of artists of colour, and he wanted to be a part of the movement in his own way. The city’s rough state and lack of paid advertisers meant they had many of the black panels in the subway for which Haring would become well-known and Haring had to be prolific, in order to be seen by as many viewers as possible.

His friends also emphasise his business acumen: “Keith had an inherent need to have a dialogue with people, and he knew what he was doing, for crying out loud. He was sending a photographer around every place he did the drawing to photograph every drawing.” It worked. The next year, Haring’s art was displayed on some of the massive billboards at Times Square. Around that time, he is living with Scharf and Samantha McEwen, and reports collectors coming to his apartment to buy works for the first time. Haring recalls the story of a man from London who bought ten drawings, and states “it’s the first time that I’ve got over a thousand dollars in my hand. And for the first time in my life realising that I can live off being an artist.” Dealers and collectors soon begin to fight over Haring’s work, which he complains about in the interview, calling them “creepy”: “Already, they’re trying to rip me off for whatever they can.”

Haring is making good money by this point – within a few days of one of his shows, he had sold a quarter of a million dollars in work. This time also marks the Wall Street Great Bull Market, a turning point in the city’s history and a time of enormous prosperity. Haring begins to be offered exhibitions all over the world, where both his artworks and his painting style are popular, and many begin to view his creative process as a performance in itself. Scharf notes how “Keith was an amazing person to watch paint.”

Haring is now treated as a rockstar wherever he goes, seen as exemplifying a new youth in America. He speaks about going to the club Paradise Garage for the first time, saying “he’s never been the same since.” His friends talk much about his drug use, and how his use of psychedelics has influenced his art.

Haring and Race

In the documentary, the various worlds that Haring seamlessly inhabits become obvious: his parents speak of attending one of his shows, and feeling out of place as the “oldest people there,” not staying too long. His friend Fab Five Freddy also reports how Haring’s friends of all colours and walks of life would attend and party, “so when those white folks that just went to the regular art world things would show up, they’d be blown away.”

In an interview, Haring speaks of the universality of his work, and the controversy it raises. He mentions an incident at the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia, where he had created a glass mural that was meant to be displayed for three months. Some people saw his work as appropriating from Aboriginal culture, until a brick was thrown through one of the glass panes within two weeks of its creation.

The documentary briefly touches on the racial aspect of Haring’s life and work, how he was constantly surrounded by people of colour and accusations that he benefited from them, which Black friends deny. The film could probably have been developed further, exploring these dynamics in depth, but chooses to stay fairly superficial.

Haring in His Prime

With his star on the rise, the documentary covers how Haring begins to throw parties, which are epic and well-known. He meets Andy Warhol and begins to cavort more with celebrities, including Madonna, Brooke Shields, Yoko Ono, and Farrah Fawcett. Friends speak about how he loved fame and notoriety, relishing recognition.

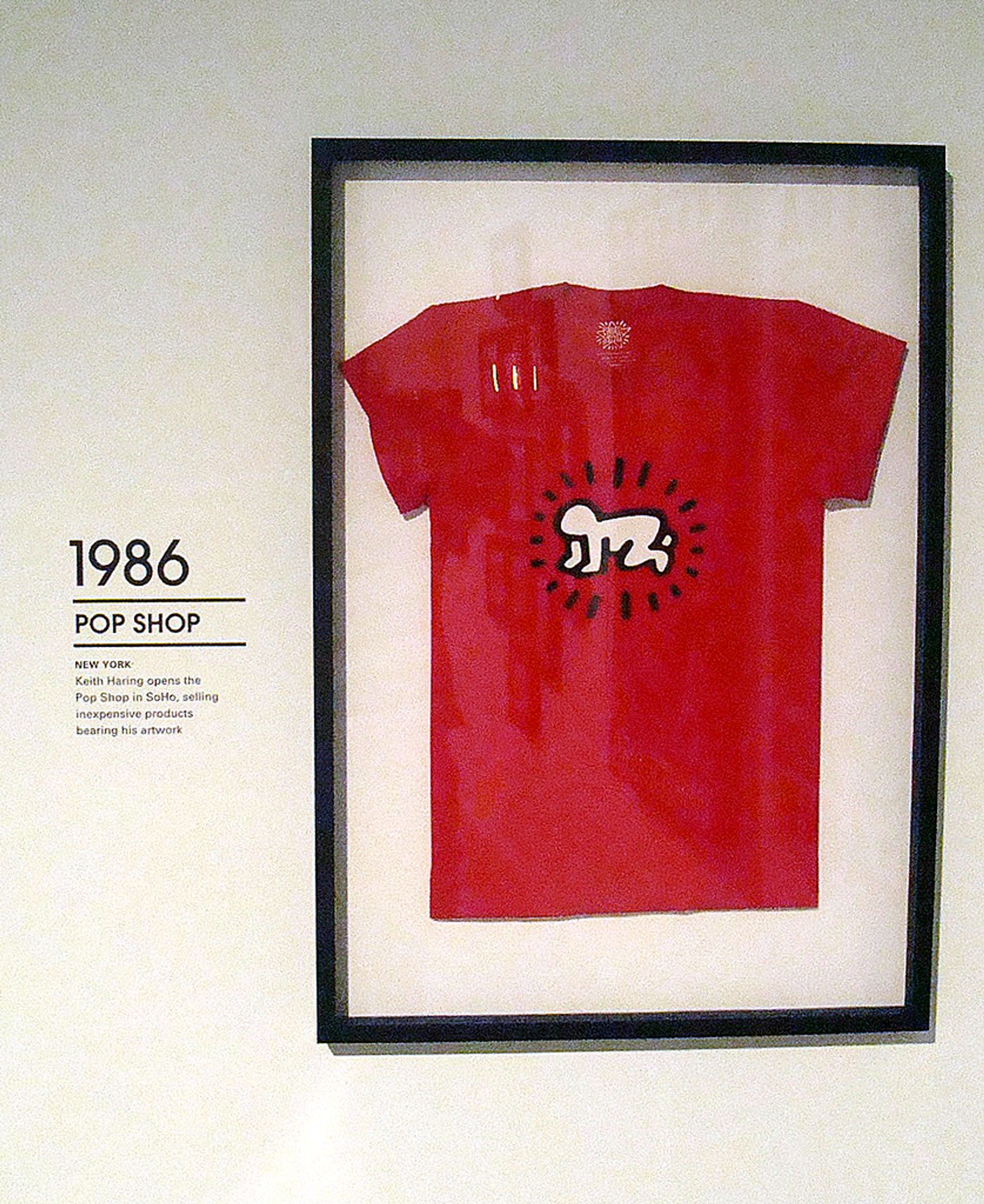

Warhol’s sense of “art as business” appealed to Haring, and weighed heavily in his decision to open the Pop Shop. Haring knew he would be criticised for it, and Shafrazi talks about how it never made money – its purpose was purely ideological. Haring was accused of selling out, however, and friends note how Haring read all the reviews about it, and it upset him.

The AIDS epidemic kicks off, and Haring mentions how his first friend who died was Klaus Nomi, who he had known from his Club 57 days. This affects him deeply, and he begins to say ‘yes’ to everything and live more fearlessly – even before his own diagnosis. He takes on more and more public commissions, especially working around children. The film focuses on Haring’s 1986 banner created with high schoolers, who he invited to paint within his lines. After a 3 day period, over 1000 teenagers had come. The documentary interviews one of them: “When you come from poverty, sometimes you think that that’s all there is. Every single person that you see represented on this banner had a voice, but somebody feeling like somehow your statement was important at sixteen, that changed everything. We got to see life different, and it gave you the opportunity to go ‘hey, there’s more to life than just my every day.’” It is great to witness someone who was directly impacted by Haring’s activism.

By the age of 27, Haring was showing regularly around the world and had his first solo museum at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Bordeaux, which then travelled to the Stedelijk. Nevertheless, he felt misunderstood in the United States, where many curators dismissed his style as “resembling illustration.” During that summer, Haring noticed trouble with his breathing before finding a spot on his leg, which was diagnosed as Kaposi’s Sarcoma – a classical symptom of AIDS. Haring knew he was dying, and shortly thereafter found out his ex-boyfriend Juan Dubose had died from the disease. The documentary moves into covering Haring’s AIDS activism, how he used his art to create attention and awareness. It shows footage of Haring speaking about how it is such an expensive disease, and covers how he was donating his own money to the cause.

The Final Years

The work Haring created in his last few years was darker, and Scharf points out how in many of them happiness and beauty were destroyed, including hellish scenes. Haring came out in the open about the disease in an article for Rolling Stone magazine, before having even told his own parents. He loved classical music towards the end of his life, travelled intensely, and continued to do drugs and party.

Haring’s sister tells the story of his final weeks: In January 1990, Haring attended the inauguration of Mayor Dinkins in New York, where he contracted a difficult chest cold. Scharf speaks of how his “battery just died”, and shows Haring’s final drawing – a half baby, with only two legs, tremulous. He continues: “he struggled so bad, he really wanted to show that he could still do it, and it was really hard for everyone.”

The film cuts to Haring’s parents wearing shoes with some of his designs. His dad mentions how his are “a bit more on the flashy side, so I don’t wear them much, I’m not a flashy, loud guy.” His mother wears a necklace with the baby motif, while explaining how Haring always said “the baby was a symbol of life.”

The documentary’s final sequence begins by informing the viewer of how Haring made more than 10.000 individual pieces of art during his lifetime, and covers the impact of his Foundation, which has donated $20 million to causes close to the artist since 1990. It also highlights Haring’s commercial appeal, as evidenced by his hundreds of collaborations. Finally, it states how “since his death, Keith has had more than 70 solo museum shows, with his work in over 60 museum collections worldwide.”

This documentary is a touching tribute to a modern icon. Viewers are able to get a glimpse of Haring’s personality, his life story and his bravery in facing adversity. It is also incredibly focused on him, with Warhol barely mentioned and Jean-Michel Basquiat omitted entirely. While this fails to provide appropriate context about the New York art scene of Haring’s time, it also means it can spend more time focusing on remembering Haring for who he was. Keith Haring: Street Art Boy offers an extraordinary insight into the life of an artist who lived and created with boundless energy, significantly impacting the social, cultural, and political landscapes of the 1980s until his untimely death in 1990.