After

Second Version Of The Triptych

These prints reproduce the panels of Francis Bacon’s Second Version Of The Triptych (1944), itself a reworking of a 1944 painting. Replete with Bacon’s grotesque humanoid figures, these works consolidate his art’s mythology, in which these forms symbolise numerous traumas— from war to guilt surrounding the artist’s sexuality.

Francis Bacon After Second Version Of The Triptych for sale

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

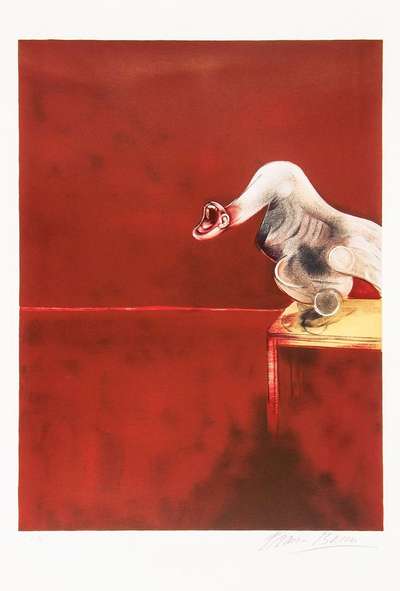

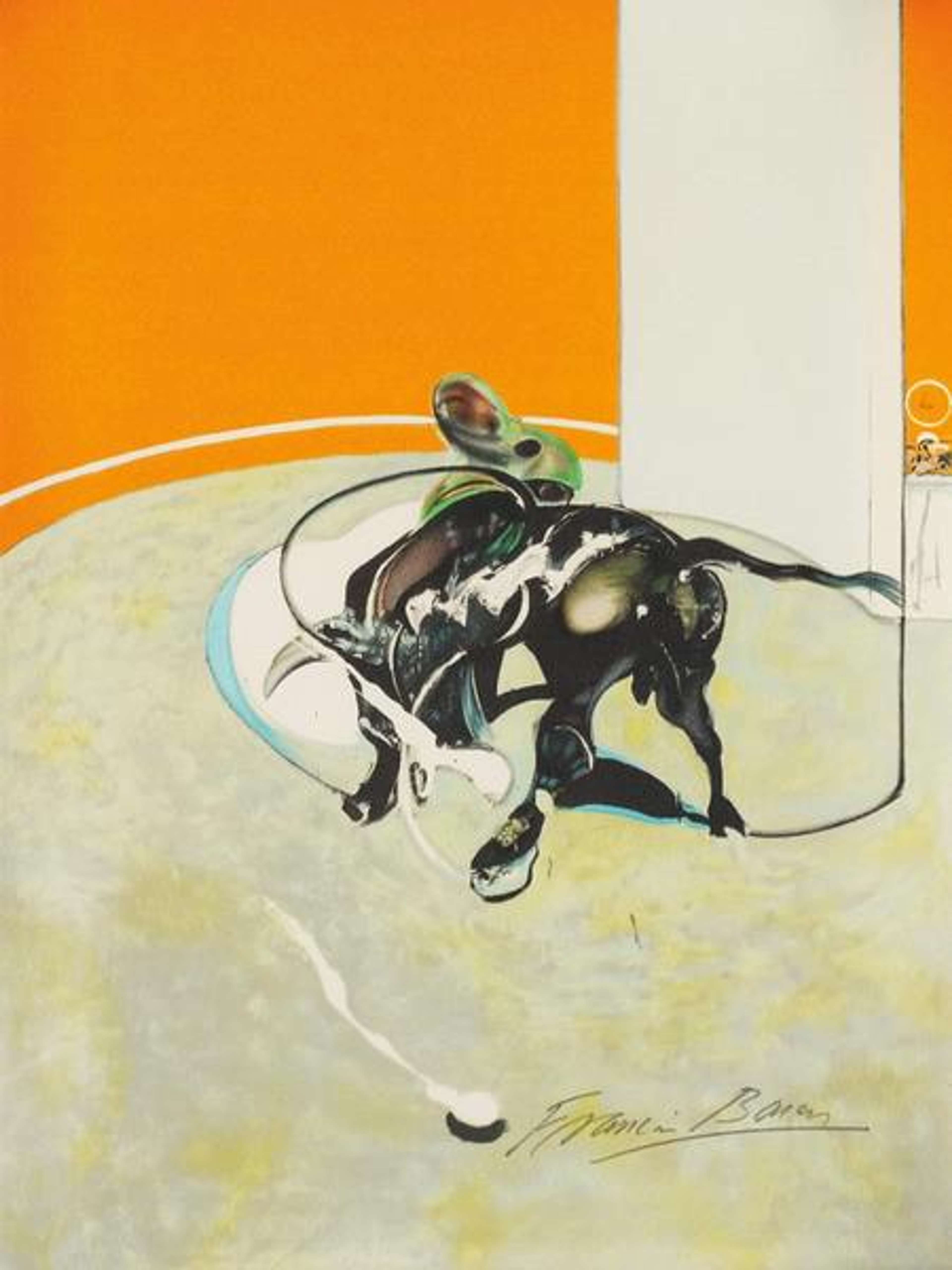

This collection of prints takes after a 1988 painting by Irish-born British artist Francis Bacon. Entitled Second Version Of The Triptych 1944, the painting is a reworking of the artist’s 1944 piece, Three Studies For Figures At The Base Of A Crucifixion. The latter of these works, produced during the final year of World War II, is a particularly visceral painting; replete with semi-anthropomorphic, semi-humanoid forms, for many it serves as a shocking visualisation of both the horrors of war and the ruined state of the world — and humanity — in its aftermath. Perhaps the most well-known feature of Bacon’s œuvre, the work was deeply shocking to those who saw it when it was first exhibited at London’s Lefevre Gallery in 1945. No typical crucifixion, the triptych mixes Christian and Ancient Greek traditions, the distorted forms appearing in each segment referring directly to the Eumedes – or ‘furies’ – of Aeschylus’s tragedy, Oresteia.

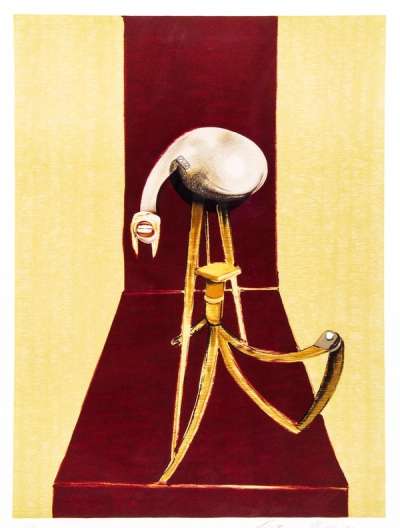

The 1944 painting is often credited, alongside Bacon’s Study After Velázquez’s Portrait Of Pope Innocent X (1953), with kickstarting the artist’s long and successful career. The 1988 reworking of this tripartite crucifixion image, then, constitutes a kind of painterly retrospection on Bacon’s part; revisiting the same odd, spherical, and distinctly grey creatures that adorned the 1944 painting, Bacon nonetheless depicts them on a much larger scale - the 1988 copy being almost twice the size of the original. Other minor points of discontinuity are apparent: replacing the orange colour of the 1944 painting is a dark, crimson hue that makes up much of the background to the work’s left and right panels. In the centre panel, a bulbous form with a long neck – and a set of human-like teeth – stands atop an abstracted plinth or stool. Behind and below it stands one of Bacon’s signature framing devices: an at once flat and three-dimensional conical of dark red paint.

The reasoning behind Bacon’s creation of this similarly monstrous 1988 copy of a 1944 painting is unclear. Three Studies For Figures At The Base Of A Crucifixion (1944) might have been inspired by Bacon’s time as an air raid warden in Blitz-era London, as some have speculated; however, the theme of the crucifixion had been a feature of Bacon’s œuvre since as early as 1933 when, at the age of 23, he painted the oil canvases Crucifixion and Crucifixion With Skull. Together with the blatant sexual themes posed by the figures in both the 1944 and 1988 triptychs, this work perhaps relates to Bacon’s persistent feelings of guilt about his sexuality. A repeated act of heavily staged sacrifice, could Second Version Of The Triptych 1944 have been designed to rid Bacon of his anguish?