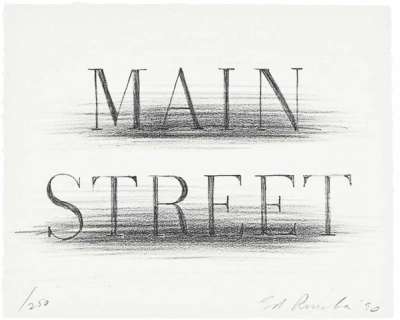

OOO © Ed Ruscha 1970

OOO © Ed Ruscha 1970

Ed Ruscha

239 works

Key Takeaways

Ed Ruscha’s art is deeply shaped by his exposure to artists and writers who pushed the boundaries of traditional representation and embraced the unconventional. Duchamp’s readymades, Johns’ symbols, and the haunting visions of Ballard inspired Ruscha to explore language, identity, and landscape in ways that were simultaneously subversive and engaging. His work is a testament to how varied artistic influences can intersect to produce a unique, transformative vision.

Ed Ruscha's creative journey, characterised by his iconic use of inventive typography and banal imagery, was shaped by a rich spectrum of influences. Far from mere stylistic choices, these elements reflect a broader lineage that stretches from early modernists, who first merged language with visual art, to literary and conceptual pioneers challenging art’s very definition. Through these influences, Ruscha developed a unique style that transcends the everyday, positioning American culture within the realm of “high” art to reveal a nuanced, reflective portrait of modern American life.

J.G. Ballard: Dark Narratives and Dystopian Visions

British author J.G. Ballard's writings delve into the darker side of modernity, creating dystopian worlds that explore humanity’s fragile relationship with urban landscapes, technology, and social decay. His works, like High-Rise and Crash, dissect the psychological impact of hyper-modern environments that isolate and alienate individuals, resulting in surreal, often violent, breakdowns in social order. This exploration of desolate, man-made spaces resonated with Ruscha, whose work often juxtaposes beauty with bleakness, and who, like Ballard, crafts images that challenge viewers to confront discomfort hidden within the familiar.

Ruscha’s 1984 painting, The Music from the Balconies, captures Ballard’s influence with haunting precision. In this piece, a tranquil landscape is disrupted by a foreboding quote from High-Rise; “The music from the balconies nearby was overlaid by the noise of sporadic acts of violence.” This striking sentence, embedded within the calm scenery, evokes an unsettling sense of impending chaos that threatens to shatter the facade of peace. Ruscha’s integration of Ballard’s words emphasises the tension between surface calm and the dark realities that lie beneath, creating a surreal, cinematic quality that seems to reflect not only Ballard’s world, but also a kind of psychological landscape. Here, the scene becomes a metaphor for the human psyche; a seemingly serene image masking the potential for unrest.

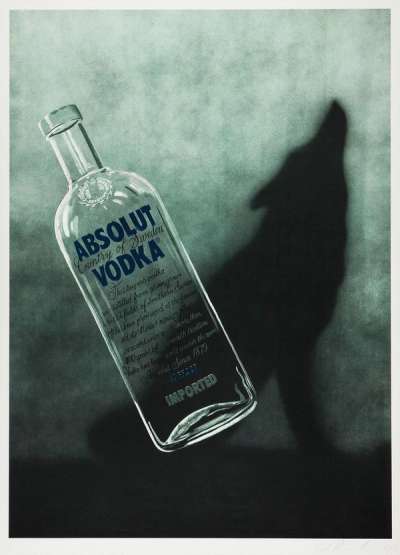

Ballard’s influence encouraged Ruscha to use his art as a vehicle for subtle social critique, infusing his depictions of urban landscapes and commercialised phrases with a sense of unease. Like Ballard’s dystopian narratives, Ruscha’s works often address the alienation inherent in urban life and the anonymity of consumer culture. His pieces transform seemingly innocent phrases and everyday images into symbols of a society where beauty and superficiality coexist.

Marcel Duchamp: The Power of Everyday Objects

Marcel Duchamp, a pioneer of Dada and Conceptual Art, revolutionised the art world with his readymades; ordinary, functional objects recontextualised as works of art. Duchamp’s approach challenged conventional notions of artistic value and aesthetics, asserting that the idea behind an object could carry as much, if not more, significance than the object itself. This conceptual innovation profoundly influenced Ruscha, who embraced Duchamp’s philosophy and applied it to the iconic but overlooked features of American life. In capturing everyday symbols like gas stations, parking lots, and the Hollywood sign, Ruscha transformed these ordinary scenes into subjects of artistic inquiry, suggesting that art could exist in places often disregarded or dismissed as banal.

Ruscha’s 1963 artist’s book, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, exemplifies his Duchampian approach. In this series of photographs documenting gas stations along Route 66, Ruscha treats each station with an impersonal, almost clinical detachment. There’s no embellishment or romanticisation, just stark, matter-of-fact images that reveal the utilitarian design of these roadside fixtures. This unembellished presentation echoes Duchamp’s practice of reframing mundane items, encouraging viewers to pause and consider the cultural weight of structures that might otherwise seem unremarkable. Duchamp’s influence inspired Ruscha to elevate these gas stations to the level of “art”, positioning them as symbols of American mobility, consumerism, and uniformity.

Duchamp’s ideas also allowed Ruscha to critique the commodification of American culture with subtlety and irony. By cataloguing ordinary sites and consumer symbols, he subverted traditional expectations of beauty and value in art, inviting his audience to engage with American consumer culture through an ironic lens. Just as Duchamp used everyday objects to challenge the role of the artist and the art object, Ruscha used gas stations, parking lots, and Hollywood landmarks to confront the homogeneity and commercialism underlying the American landscape. Through Duchamp’s conceptual framework, Ruscha redefined these familiar spaces as complex reflections of a consumer-driven society, effectively turning the mundane into an exploration of cultural identity.

Jasper Johns: Symbols and the American Identity

Jasper Johns, celebrated for his groundbreaking use of familiar symbols like flags, targets, and maps, redefined the American art scene by challenging viewers to see beyond the surface of everyday imagery. His work blurred the lines between abstraction and representation, allowing artists to recognise the rich potential within commonplace symbols. This approach had a lasting impact on Ruscha, who saw in Johns’ art a powerful model for how images and ideas could coexist on a single canvas. One piece in particular, Target with Four Faces (1955), left a profound impression on Ruscha, leading him to explore how recognisable symbols, especially words, could invite deeper engagement with the nuances of American identity.

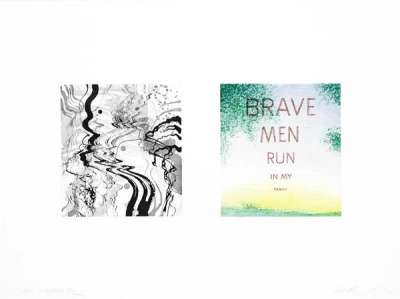

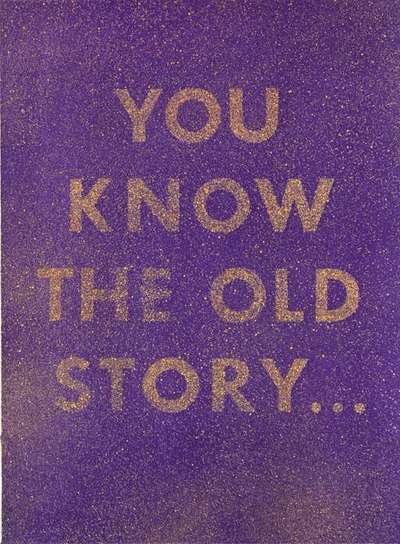

Ruscha’s iconic word paintings, like OOF (1962) and Honk (1962), echo Johns’ technique of recontextualising symbols, but by turning words themselves into visual objects. By placing short, punchy words in bold typographic styles against solid backgrounds, Ruscha asked viewers to contemplate their form as much as their meaning. These words hover between the abstract and the representational, much like Johns’ symbols, becoming more than just letters on a canvas. For instance, the word “OOF,” painted in large, yellow block letters, strikes viewers as both an exclamation and a solid, almost tangible object. Here, Ruscha uses text to evoke physicality and to blur boundaries between image, sound, and meaning, expanding on Johns’ exploration of how familiar symbols can resonate emotionally and conceptually.

Johns’ exploration of the American flag also influenced Ruscha’s engagement with American cultural icons. Where Johns presented the flag as a canvas subject to reinterpretation, Ruscha used words and urban images, like gas stations and signage, as symbols of American life. Just as Johns invited viewers to reexamine the flag’s cultural meanings, Ruscha’s works asked audiences to reflect on the messages embedded in everyday language and the constructed landscapes of modern America. His choice of words, often drawn from popular culture or advertising, embodies the American vernacular, revealing how deeply rooted phrases and symbols shape collective identity. Through this approach, Ruscha’s word paintings become more than simple displays of text; they encapsulate the rhythms, desires, and ambiguities of American life, just as Johns’ flags and targets did.

Moreover, Johns’ influence encouraged Ruscha to treat symbols not just as carriers of meaning, but as forms with inherent aesthetic value. By isolating words and symbols from their usual contexts, Ruscha, like Johns, compelled his audience to confront the aesthetic qualities and textures of familiar imagery, giving these symbols new resonance. In the same way that Johns’ flags and targets became meditations on identity and perception, Ruscha’s word paintings highlight the layered roles of symbols as both visual forms and cultural signifiers, revealing an American experience that is as nuanced and layered as the imagery he employs.

The American West: A Mythic Landscape

Having grown up in Oklahoma and later moved to Los Angeles, Ruscha’s life has been steeped in the vast landscapes, expansive highways, and unique cultural terrain of the American West. This environment of open skies, desolate stretches, and roadside culture became a foundational influence on his art, shaping how he captured the peculiar beauty and subtle melancholy of the Western frontier. Ruscha’s treatment of geographical subjects, such as gas stations, open skies, and mountain vistas, encapsulates not only the physical vastness of this region, but also its symbolic weight as a land of opportunity, solitude, and boundless freedom.

Ruscha’s works, like Standard Station and Twentysix Gasoline Stations, evoke a sense of both awe and ambivalence toward this mythic landscape. In Standard Station, for instance, he transforms a seemingly ordinary gas station into a monumental structure, silhouetted against a bright, clear sky. This isolated, towering image of a gas station on an empty road becomes a quintessential emblem of the American West, a place where endless highways symbolise both the allure of freedom and the starkness of isolation. By capturing these roadside scenes with a detached, almost clinical gaze, Ruscha imbues them with an unsettling quality, hinting at the loneliness and transience underlying the American dream of expansion and independence.

At the same time, Ruscha’s use of advertising-inspired phrases in conjunction with these images highlights the creeping commercialisation of the Western landscape. The text in his work often mimics catchy slogans or billboard advertisements, inviting viewers to consider how American culture has commodified even its most iconic, untouched spaces. In works like Pay Nothing Until April and Every Building on the Sunset Strip, Ruscha juxtaposes consumerist phrases with grand, serene landscapes. This pairing of advertising language with scenes of natural or urban Western expanse comments on how the American West, once seen as a wild frontier, has been shaped and sold as part of a larger capitalist narrative. Ruscha’s work thus subtly critiques this commodification, exposing the contradictions between the romantic ideal of the West and its reality as a landscape increasingly shaped by consumer culture.

Ruscha’s work is a vibrant crossroads of influence, skill, and cultural critique, shaped by artists and movements that encouraged him to redefine what American art could be. From Ballard’s dark visions of urban alienation to Duchamp’s revolutionary embrace of the everyday object, Johns’ symbolic reframing of American identity, and the mythic resonance of the American West, each inspiration enabled Ruscha to construct a layered visual language uniquely his own. His art captures the paradoxes of American life; the tension between beauty and commercialism, the power of simplicity to evoke complexity, and the profound within the mundane. Ruscha’s adoption of words, symbols, and familiar landscapes transforms these elements into lenses through which viewers can reflect on American culture’s promises and contradictions.