Damien Hirst’s Preoccupation with Kaleidoscopes

Domini Est Terra (diamond dust) © Damien Hirst 2010

Domini Est Terra (diamond dust) © Damien Hirst 2010

Damien Hirst

677 works

Synonymous with boundary-pushing creativity and profound commentary, Damien Hirst's oeuvre consistently challenges perceptions and evokes deep introspection. Among his myriad explorations, one thematic preoccupation stands out both for its visual splendour and intricate symbolism: the kaleidoscope. These multi-faceted designs, bursting with colour and movement, are more than just a captivating visual feast; they serve as a lens through which Hirst investigates life's complex issues, finding parallels in the ever-shifting patterns of his works. The kaleidoscopes also reflect issues that feature prominently in the rest of his art, including the transient nature of life, the tension between chaos and order and a concern with spirituality and the cosmic.

Damien Hirst's Artistic Evolution

Hirst's journey through the art world has been as multifaceted as the kaleidoscopic patterns he has explored. After gaining prominence in the late 1980s and early 1990s, he emerged as a pivotal figure among the Young British Artists (YBAs). Central to his oeuvre is the exploration of the ephemerality of life, and Hirst’s most famous works often tread the line between the natural world and human artifice. This is exemplified by pieces such as The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living, which showcased a tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde and has entered pop consciousness.

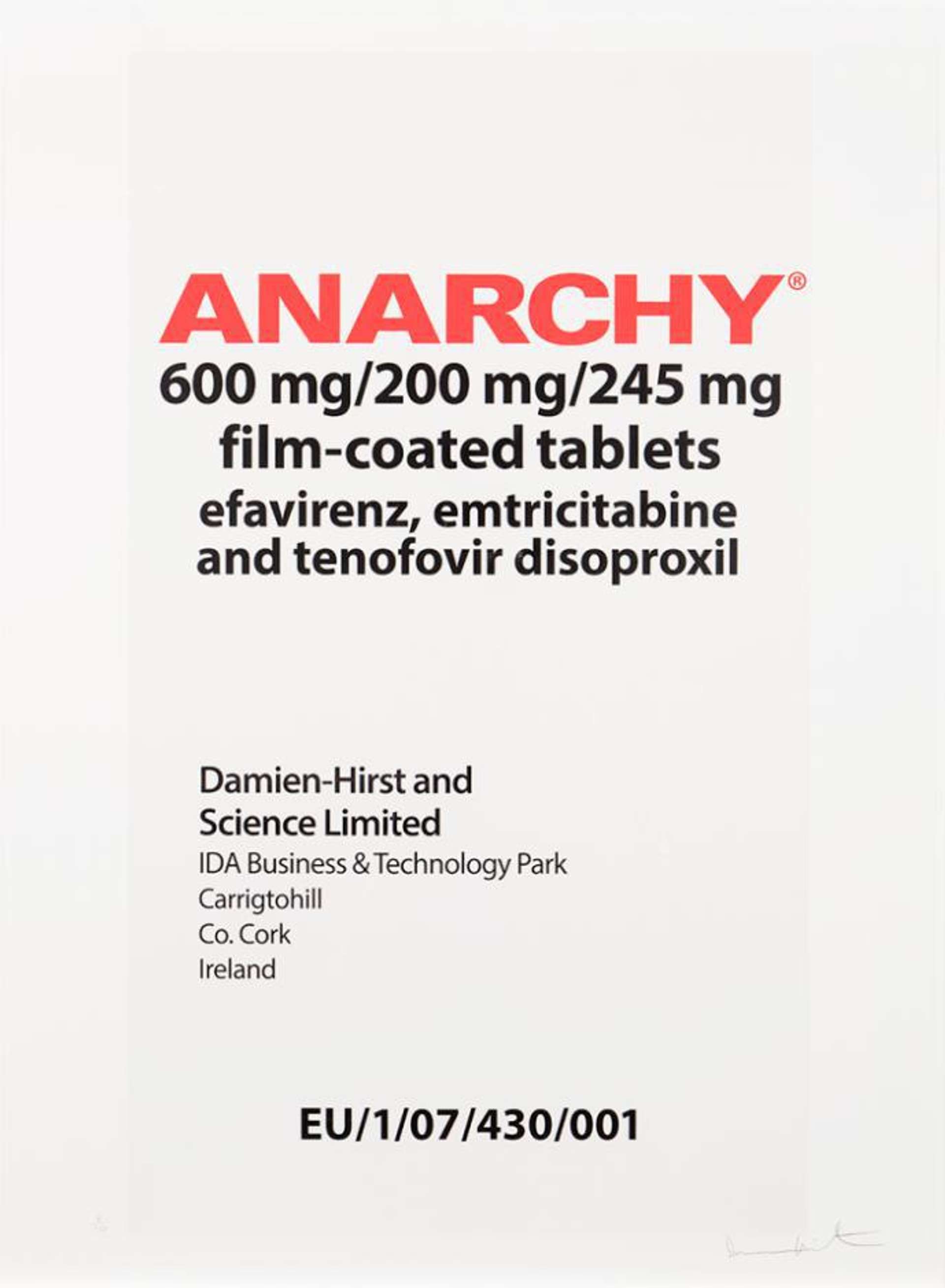

Away from these visceral depictions, Hirst’s pharmaceutical series presented a more clinical viewpoint on life: his Spot Paintings and medicine cabinets delve into society's relationship with the pharmaceutical industry, juxtaposing the aesthetic allure of pills against broader issues of dependence and healing. In the past few years, Hirst has continued to surprise and polarise the art community. Works such as Treasures From The Wreck Of The Unbelievable and his numerous collaborations have showcased his insatiable appetite for reinvention. Throughout his career, Hirst has consistently defied expectations, whether evoking shock or awe, cementing his legacy as one of the most influential artists of our era.

Butterflies in Hirst's Oeuvre: Symbolism and Depth

In one of his most iconic installations – In And Out Of Love, set at the Yale Arts Centre in 1991 – Hirst attached butterfly pupae to white painted canvases in a humid exhibition room. Viewers were then able to observe and participate in the butterflies’ entire life cycle.

Since then, butterflies have played a significant part in Hirst’s oeuvre, and never more than in his kaleidoscopic works. At its core, this creature embodies a profound representation of transformation, charting a journey from caterpillar to its resplendent final form and embodying themes of life, death and rebirth – all themes highly significant for Hirst. This metamorphic tale, which he frequently revisits, serves as a poignant reflection on the transient nature of existence. Butterflies have historically been revered as symbols of the soul and resurrection in various cultures, infusing Hirst's work with undertones of spirituality and existential pondering. Hirst himself has cited a Victorian tea tray as inspiration for his use of the motif.

By integrating real butterflies onto canvases, Hirst challenges traditional boundaries of art and notions of authenticity, and he has faced harsh criticism for his inclusion of real animals and insects in his art. This in itself introduces an additional layer to his work, prompting viewers to wrestle with moral dilemmas and reflect on art's role in society. Nevertheless, for Hirst the butterfly's delicate and ephemeral beauty stands as a metaphor for life's cyclical nature, prompting an important contemplation on the fleetingness of beauty and life itself.

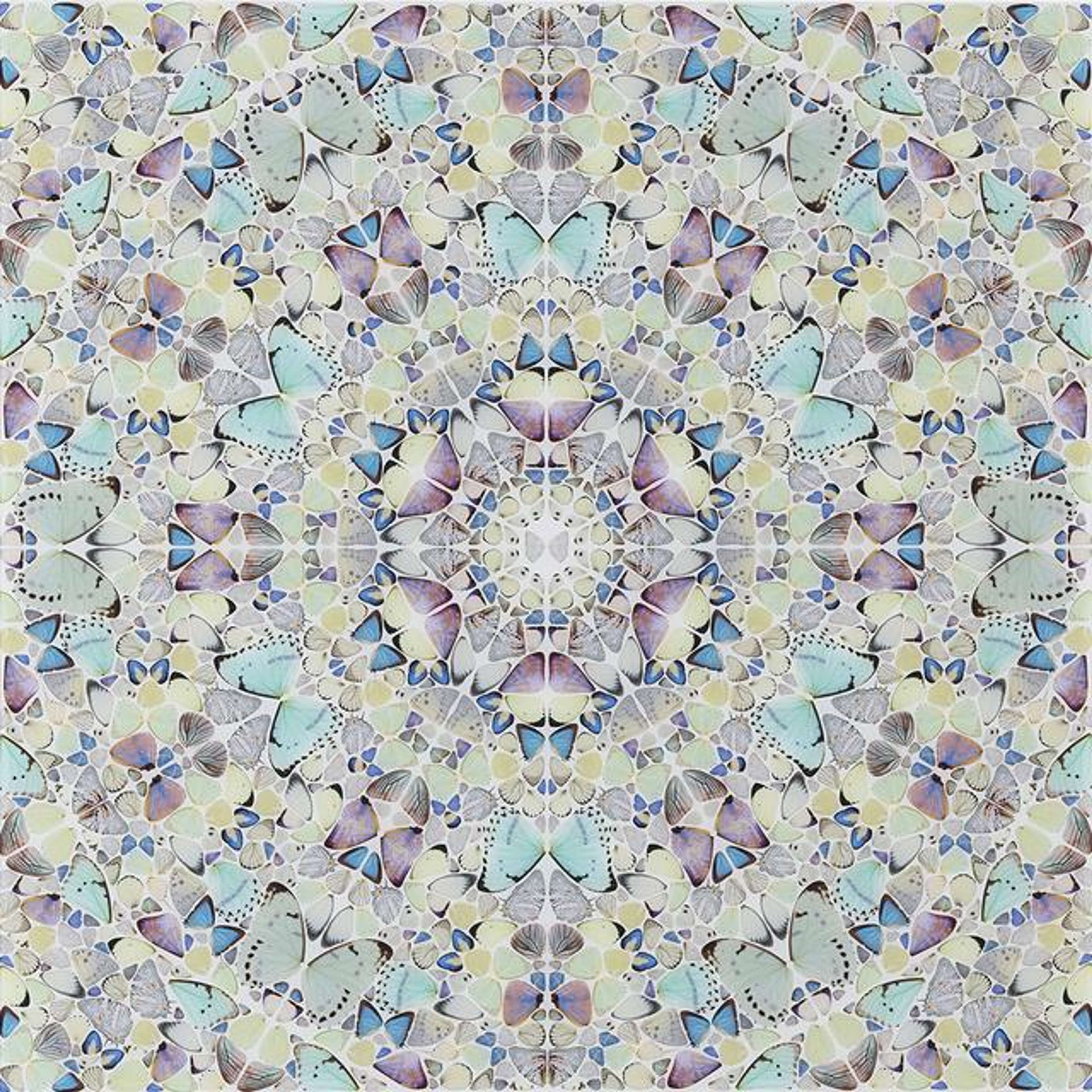

Kaleidoscope (2001)

Kaleidoscope was Hirst's first foray into the subject. Beginning in 2001, the artist created several paintings and prints in this style, featuring intricate designs composed out of thousands of colourful butterfly wings. Hirst creates the works by arranging the butterfly wings in geometric patterns and placing them onto household paint. Each design is unique, but there is a strong sense of colour and composition throughout.

The series began with It’s A Wonderful World, its diamond-shaped canvas becoming a motif echoed in later pieces like Sceptic and Faithless. The Kaleidoscope works were first displayed at London's White Cube in 2003, as part of the exhibition Romance in the Age of Uncertainty. By 2007, a comprehensive solo exhibit titled Superstition was staged at the Gagosian Gallery in both London and Beverly Hills. The prints are named with words with strong religious significance, such as Covenant, Deific and Miracle.

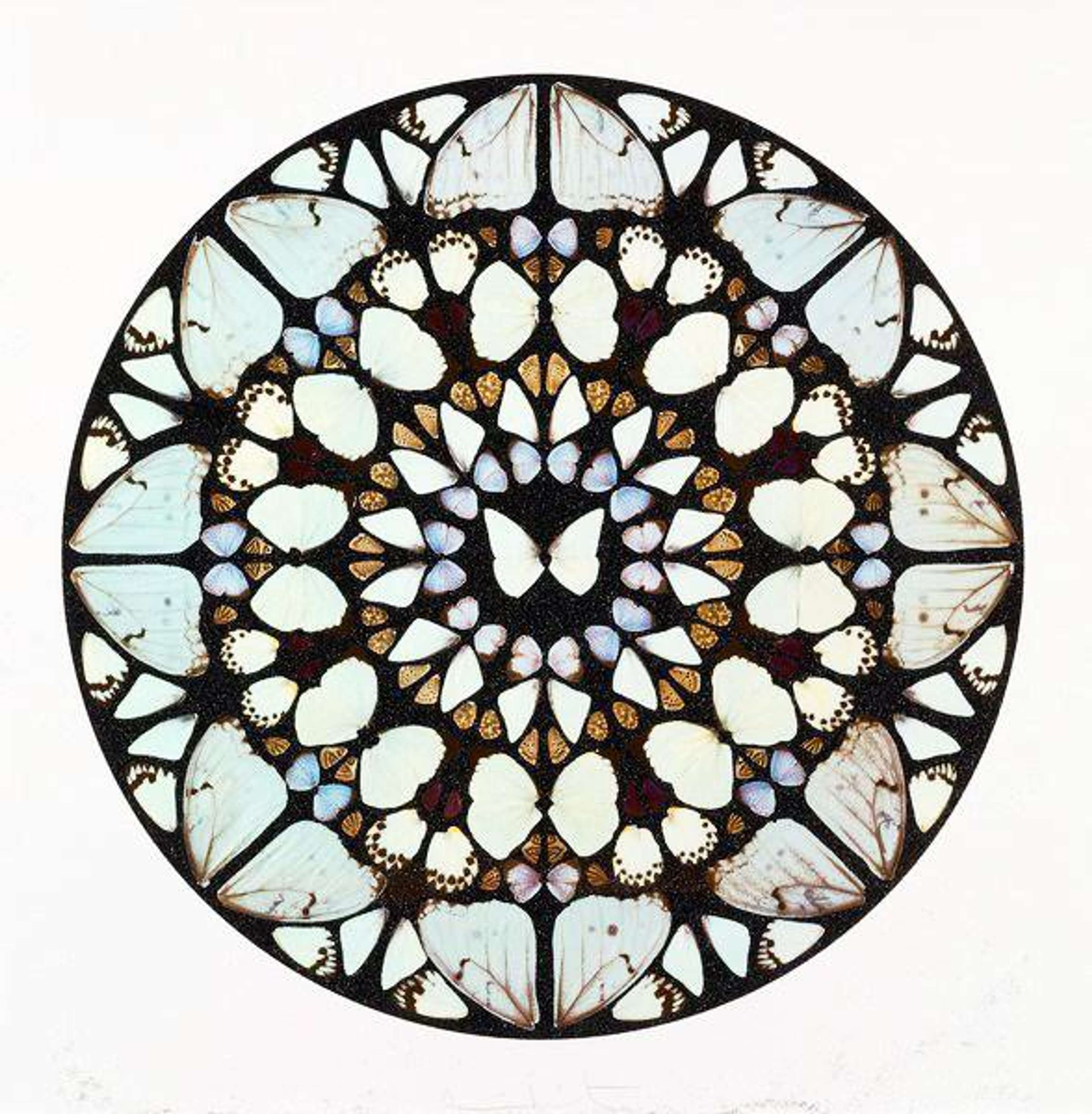

Cathedral (2007)

Leaning into the similarities between kaleidoscopes and stained glass, Hirst’s Cathedral series from 2007 builds on the previous series' use of butterfly wings and geometric arrangements. In this case, however, the works were inspired by windows from cathedrals around the world: St Peter, Santiago de Compostela, Notre Dame, St Paul, amongst others.

By drawing such a strong association with Christianity, Hirst draws a parallel between the re-birth of the butterfly and the resurrection of Christ. He also emulates the spirituality that the symmetrical nature of mandalas have evoked in a variety of religions, from Buddhism to Christianity. This would be a theme that he returns to again and again in future works.

Psalms (2008-2015)

This collection of paintings and prints began to be produced in 2008, and each work was named after psalms from the Old Testament. This is one of Hirst’s most symmetrical series, with most of the patterns revolving around a circular motif. It is also one of his largest series, with over 150 prints to choose from. Despite this, the works show incredible variety and versatility, and no two prints look the same.

Like many of Hirst’s kaleidoscopic artworks, the prints in this series demand the viewer pay close attention to the intricate details present within the composition.

Sanctum (2009)

The series Sanctum is composed of six artworks, continuing on Hirst’s obsession with symmetry and butterfly wings. Its title alone suggests tranquillity, in a way that is reminiscent of Cathedral and Psalms. This series is interesting due to the fact that its compositions are much darker than the previous iterations: placed against a black background, the butterfly wings are made to look softer and more watercolour-like and, additionally, draw an even stronger connection to church windows. When compared to the previous series using the same motif, the colours are decidedly more muted and less flashy, with the result looking more sombre than before.

The prints are named after different areas of a church: Dome, Altar, Belfry, Spire, Chancel and Minaret. By using these architectural terms Hirst is able to break down the spiritual power of a church, replicating in the works how each of these sections tend to make the viewer feel.

H6 The Aspects (2015)

In a series that marked a return to this composition style after 6 years, Hirst issued five prints meticulously crafted in tones of a peaceful ultramarine blue. Unlike many works in his previous series, each print in The Aspects is perfectly symmetrical, further emulating the aspect of a kaleidoscope. The titles of the prints include common virtues found in a range of religions – Grace, Patience, Mercy, Goodness and Truth. This reflects Hirst’s fascination with spirituality and the human psyche.

H6 The Elements (2020)

This series comprises four giclée prints inspired by the four elements: earth, air, fire and water. The butterfly wings' colours are dispensed according to the element, with Fire being composed of bright oranges and reds, Water mostly of blues and whites, Earth of brown and gold tones and Air of whites and lilacs.

Hirst first explored the elements in his 1992 room-sized installation Pharmacy, where he created glass bottles filled with coloured liquids to represent each of the four. As evidenced even at this early date, the four elements play an important part in Hirst’s interest in questioning life and death, medicine and cures, and in his belief in the mythical – as in the past, it was believed that the elements could be used to heal the sick. This means The Elements is often seen as a tie-in between many of Hirst’s artistic explorations.

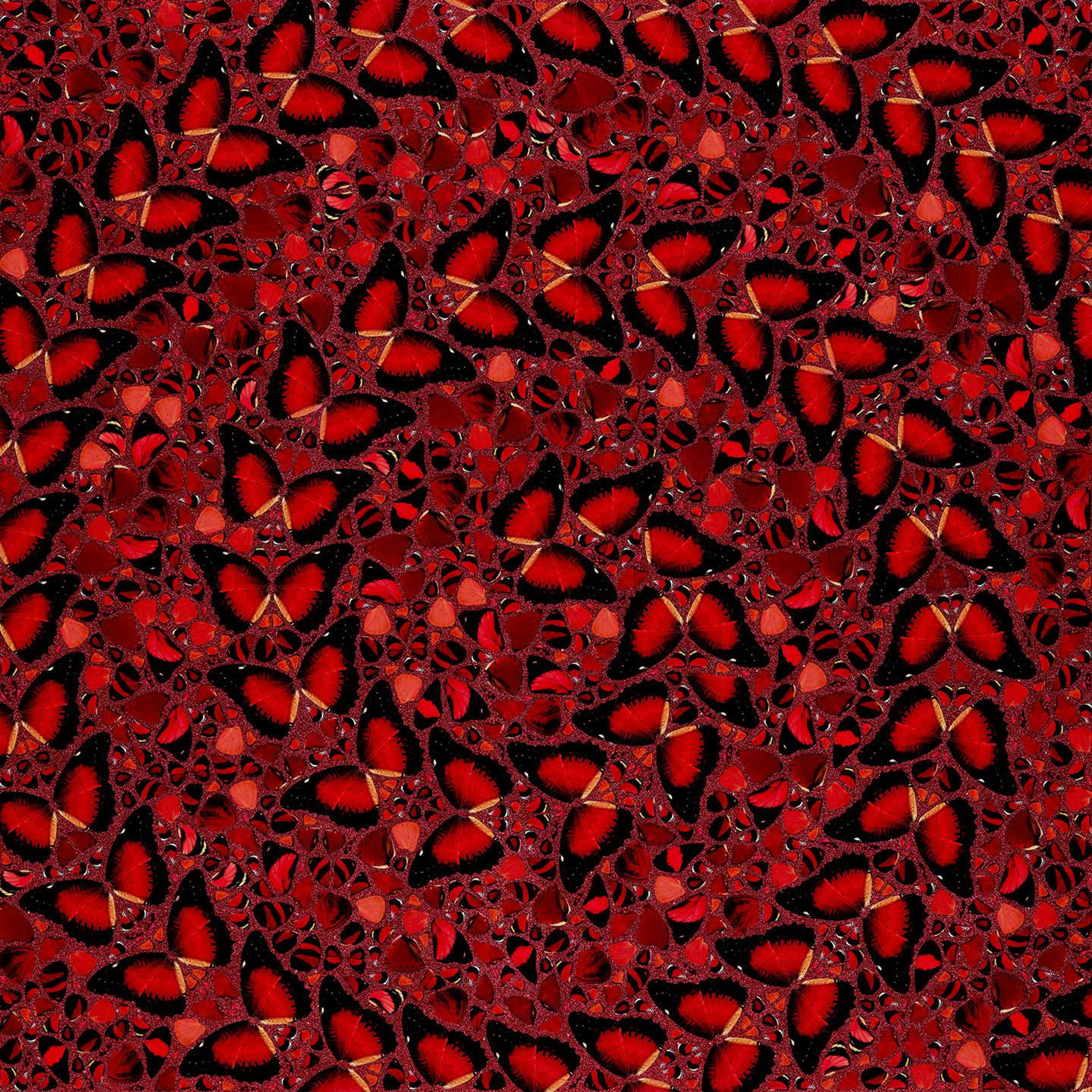

H10 The Empresses (2022)

Hirst's The Empresses series, unveiled for HENI Editions, comprises five distinct prints crafted in laminated giclée on aluminium composite with screen-printed glitter. The artworks exude an essence of power and royalty thanks to Hirst's deliberate choice of a red colour palette: this chromatic selection is steeped in historical significance, a nod to its perennial associations with regality. The glitter imbues transient movement to the butterfly, reminiscent of their fleeting wings, and adds a sense of luxury to the works. The series' title is a playful double-entendre, referring to the butterfly species while also alluding to the political stature, as each artwork draws its name from a historically significant empress.

While most compositions embrace a symmetrical mandala-esque design, H10-3 Theodora stands out as its central butterfly sits off-kilter. HENI Editions adds that this unique arrangement evokes "a formation reminiscent of the female gender symbol," and suggests an homage to the landmark feminist reforms introduced by the Empress Theodora of the Byzantine Empire, renowned for her unparalleled rise from societal fringes to imperial opulence. Other important women in history are also referenced: from the formidable Empress Wu Zetian of China, who etched her mark as the nation's sole female emperor; to the influential Empress Nūr Jahān of the Mughal Empire, who wielded unprecedented power behind the throne; Empress Suiko of Japan, who steered her nation through significant cultural and political metamorphoses; and Taytu Betul of Ethiopia, a beacon of anti-colonial resistance and instrumental in Ethiopia's victorious defence against Italian colonisation.

These artworks were not confined to their physical form alone, as Hirst entered into the digital domain with the introduction of NFTs. This series, steeped in significance and artistry, was available exclusively for a week, from 28th January to 4th February 2022. The final count of editions was determined by the demand during this window.

Hirst's Kaleidoscope: A Metaphor for Life's Complexities

In dissecting Damien Hirst's profound exploration of kaleidoscopes, one cannot help but be drawn into a contemplation on life’s beauty and its intricacies. Hirst's meticulous arrangement of butterfly wings into mesmerising patterns, akin to the shifting shapes in a kaleidoscope, serves as a brilliant metaphor for the unpredictable and ever-changing nature of existence. Just as a kaleidoscope's patterns are birthed from a simple twist, life, too, alters its course in the face of seemingly minor shifts, presenting us with endless possibilities and challenges.

These vibrant compositions are more than mere visual delights; they are a testament to life's transient moments and the infinite beauty found within them. The butterfly, fragile and ephemeral, encapsulates the fleeting nature of life, while the kaleidoscopic designs suggest that beneath the surface chaos, there's an inherent order, a pattern that might be discernible if we look closely enough. Hirst’s use of the butterfly is especially poignant: with its life cycle representing metamorphosis and change, it becomes an emblem for the viewer’s own transformative journeys through life's many phases. Furthermore, Hirst's echoing of church windows and Buddhist mandalas in his vibrant colours and patterns highlights the spiritual dimension of our existence, subtly suggesting that within the swirling chaos of life, there might be a nexus of understanding waiting to be discovered.

The works serve as a reminder that while life is filled with complexities and unexpected turns, it is this very unpredictability that makes it beautiful. Just as we find joy in the unexpected patterns a kaleidoscope presents, perhaps we can learn to embrace life's uncertainties, finding beauty in its twists and turns and comfort in the only certainty: death. In the end, Hirst's exploration of the kaleidoscope is a profoundly philosophical journey, and a reflection on the nature of life itself.