Grotesque, Sublime & Monstrous: Horror in Art

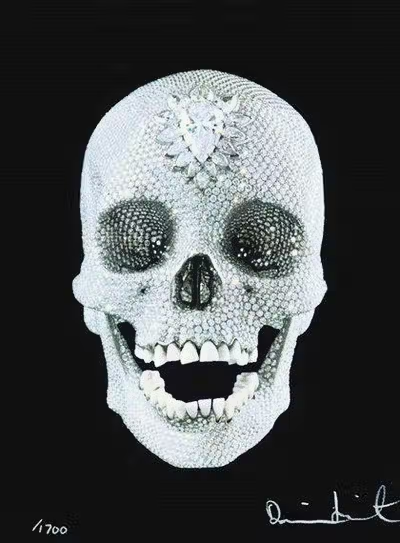

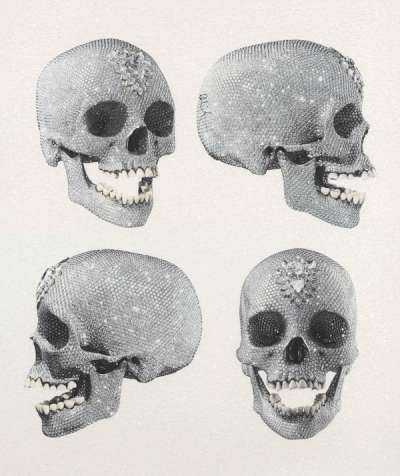

Till Death Do Us Part (purple african gold purple imperial purple) © Damien Hirst 2012

Till Death Do Us Part (purple african gold purple imperial purple) © Damien Hirst 2012Live TradingFloor

Key Takeaways

Art’s darker themes have long fascinated and unsettled audiences. Through the horror genre, artists explore the macabre and grotesque, challenging conventional ideals while pushing the boundaries of fear and beauty. Artists such as Cindy Sherman, Louise Bourgeois, and Edvard Munch incorporate these elements to express the innate anxieties of identity, mortality, and the subconscious.

Horror, often dismissed as mere fright or gore, is deeply woven into the fabric of art history as a complex exploration of inner and outer turmoil. From its roots in ancient myth and religious imagery to contemporary installations, horror serves not just to shock or disturb, but to provoke contemplation on mortality, identity, and the nature of fear. Art has long employed horror to delve into societal anxieties, to critique established ideals, and to probe into the psychological depths of individual trauma.

The concept of the sublime, deeply rooted in Western aesthetic discourse, plays a crucial role in shaping our understanding of horror. Thinkers including Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant described the sublime as a complex emotional state that blends awe with terror, where the mind is simultaneously drawn toward and overwhelmed by something vast, powerful, or beyond comprehension. This tension between fascination and fear is what gives horror its unique metaphysical depth. When viewed through the lens of the sublime, horror becomes more than just a depiction of fear; it taps into a fantastical realm where we reconcile forces that seem both compelling and monstrous.

The Grotesque and the Monstrous: Art as a Reflection of Fear

The grotesque, a concept that lies at the intersection of beauty and repulsion, has been a central aesthetic in art for centuries, transforming the familiar into the distorted. Emerging as a result of the rediscovery of ancient Roman wall decorations in the Domus Aurea during the Italian Renaissance, the grotesque evolved into an artistic language that embraced the monstrous zoomorphic. By the 18th century, the term ‘grotesque’ in English took on a different meaning, becoming closely tied to caricature and characterised by an exaggerated focus on the absurd.

By the Neoclassical era, this fascination with the strange and unstructured became considered abnormal and at odds with the natural order, leading to its contemporary negative connotations. However, the grotesque continued to thrive as an artistic exploration of the supernatural, challenging conventional ideas of beauty and normalcy, and allowing artists to delve into the darker, more unsettling aspects of the imagination. Through its many transformations, it has maintained its power to provoke, unsettle, and fascinate.

The Aesthetic of the Grotesque and the Sublime

Goya’s Los Caprichos

During the Early Modern period, the grotesque began to feature prominently in European art as a way to explore the limits of human experience. This can be seen most strikingly in the works of Francisco Goya, most notably his haunting series Los Caprichos. In these etchings, Goya intertwines the grotesque and the familiar, confronting viewers with nightmarish scenes that blur the boundary between reality and the surreal. Witchcraft, superstition, and irrationality become emblematic of a society spiralling into madness. But Goya's work transcends mere depictions of physical horror; his grotesque visions also served as damning social critiques, exposing the Enlightenment’s failure to bring about a rational and just world.

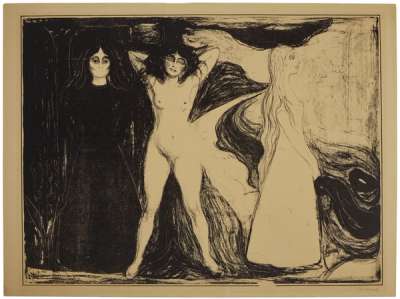

Munch’s The Scream

While the grotesque distorts the body, the sublime stretches the mind through a juxtaposition of awe and terror. Edvard Munch's work epitomises this aesthetic tension, with his iconic painting The Scream (1893) standing as a vivid expression of pure existential dread. The swirling, vibrant, nightmarish landscape becomes a distorted reflection of internal panic, blurring the boundary between the outer world and inner turmoil.

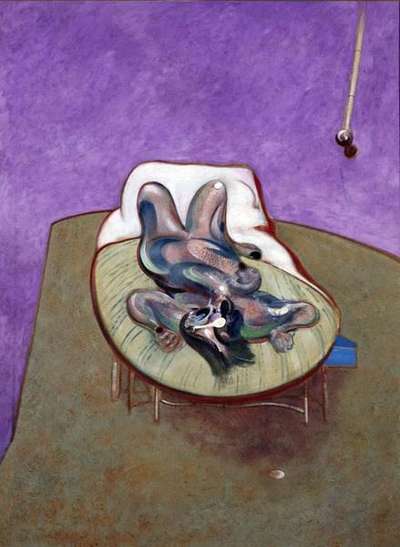

Francis Bacon: The Horror of Flesh and the Breakdown of Form

If Munch explored the horror of existence, Francis Bacon delved into the horror of the flesh. His works, known for their grotesque depiction of abstracted bodies, emphasise the fragility of the human form and the existential suffering that accompanies it. In Bacon's art, the body is not an idealised vessel, but a site of pain, distortion, and decay.

Bacon’s prints, like his paintings, evoke a profound sense of disintegration. Figures in his work appear blurred, twisted, and trapped within claustrophobic, geometric spaces. This fragmentation mirrors the 20th-century existentialist focus on the breakdown of identity and the inevitable decay of the human body. One of his most famous works, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, exemplifies this obsession with physical and spiritual suffering. Created in 1944, this triptych depicts grotesque, contorted figures that evoke a sense of torment and anguish. The work is deeply rooted in religious symbolism, drawing on the theme of Christ’s crucifixion, which is traditionally associated with ultimate sacrifice and suffering. However, Bacon's interpretation diverges from conventional religious iconography. Instead of focusing on redemption or salvation, the figures appear deformed and monstrous, their distorted forms and screaming mouths evoke visceral reactions, as if the viewer is witnessing the embodiment of psychological and emotional agony. Through these harrowing figures, Bacon delves into the depths of the horror of the flesh and existential crises that define human life.

Horror In Modern Art

Damien Hirst

The legacy of horror and the grotesque persists in modern and contemporary art. Damien Hirst’s fascination with mortality reached new heights in his iconic work The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), which features a 14-foot tiger shark suspended in a tank of formaldehyde. The shark, frozen mid-swim in its glass cage, becomes a symbol of impending horror, evoking an instinctive sense of fear while simultaneously remaining inert, distant, and untouchable. The piece taps into the sublime in the Burkean sense; instilling awe and terror in equal measure. The viewer is left to grapple with the paradox of confronting death while remaining safely removed from it. This tension between life and death, fear and fascination, is at the heart of Hirst's work. The shark’s size, its predatory nature, and its preservation in formaldehyde amplify the unnaturalness of the encounter, making death both a spectacle and a mystery.

Furthermore, Hirst’s For The Love of God series, particularly the skulls set against a black backdrop, evoke themes of horror by confronting viewers with symbols of death and decay. The piece, a platinum cast of a real 18th-century skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds, uses the skull motif to explore the tension between mortality and materiality. This tension between luxury and death aligns with horror's preoccupation with the macabre and the fragility of life, forcing the viewer to confront their own mortality in the context of an obsessively material world.

Cindy Sherman

Cindy Sherman’s work not only engages with the grotesque, but also delves deeply into the horror genre through the distortion and manipulation of her own body. By reshaping herself into exaggerated and sometimes monstrous forms, she taps into the core elements of body horror, a subgenre that centres on the grotesque transformation of the human form. Sherman's self-portraits, particularly in her Untitled Horrors series, align with the tradition of horror that explores themes of disfigurement, identity loss, and the abject; the breakdown of the boundary between the self and the ‘other’. In her photographs, Sherman warps her appearance to the point of becoming unrecognisable, conjuring a sense of the uncanny, where the familiar becomes disturbingly alien. Her images echo the work of classic horror films, where monstrous transformations, such as in Frankenstein, elicit fear by pushing the boundaries of the human body. Sherman’s ability to morph her features into unsettling hybrids embodies this tradition, forcing viewers to question the stability of identity.

The grotesque, as used by Sherman, becomes a powerful tool for critiquing societal norms, especially in relation to beauty and gender. By distorting her face and body, she breaks down traditional expectations placed on femininity, transforming what is typically seen as delicate and desirable into something horrifying and monstrous. This manipulation of the female form places Sherman’s work in dialogue with feminist horror, which often uses the grotesque to critique the objectification of women and the oppressive standards of beauty. The monstrous body in her work is not only a site of horror, but a form of rebellion against the male gaze, as it confronts viewers with questions of what lies beneath constructed ideals.

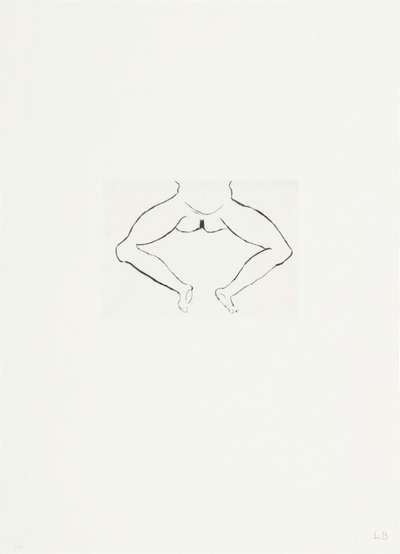

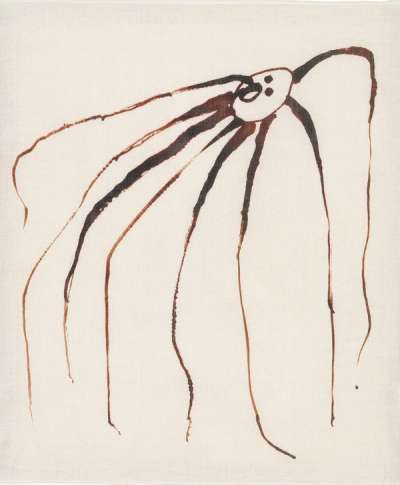

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois’ work, particularly in The Destruction of the Father (1974), embodies the horror and grotesque genres by transforming psychological trauma into a visceral, physical experience. In this haunting installation, Bourgeois translates the inner turmoil of childhood trauma into a nightmarish scene where the grotesque becomes the primary mode of expression. The tableau of a father being devoured at a familial dinner evokes a primal horror, with the act of consumption representing both rebellion against and deconstruction of patriarchal authority. Bourgeois’ work also engages with the abject; a concept crucial to the horror genre and described by philosopher Julia Kristeva as what disturbs identity, system, and order. In The Destruction of the Father, the devouring of the paternal figure breaks taboos around the family, a sacred societal structure, making the familiar environment of the home an arena of dread. This aligns with the horror genre's frequent use of domestic settings as sites of terror, where the safety of the home is often subverted and defiled. Her grotesque use of bodily forms in this work not only confronts personal trauma, but also evokes the broader fears surrounding familial relationships and identity.

Moreover, Bourgeois’ constant return to the female body, transformed and fragmented, places her within the realm of feminist horror by engaging with its themes of vulnerability, power, and the grotesque. By presenting the female body as both vulnerable and powerful, grotesque yet defiant, Bourgeois explores the anxieties surrounding gender and sexuality that horror often engages with. In line with these themes, she subverts the ‘monstrous-feminine’; a common horror trope where women are conceptualised solely as victims. In The Destruction of the Father, the monstrous act of a woman devouring her father embodies both power and violence, mirroring horror’s frequent focus on fear and bodily horror. Through the lens of the grotesque, Bourgeois forces viewers to confront their own discomfort with the body, repression, and the power dynamics rooted in family and gender, rendering her art a profound exploration of human fear.

Dorothea Tanning

Dorothea Tanning’s Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot (1970–73) encapsulates the eerie tension between the familiar and the monstrous. In this surreal installation, Tanning transforms an ordinary hotel room into a nightmarish, uncanny space where distorted bodies meld with the architecture, seeming to break free from walls and furniture. The disfigured, fleshy forms that emerge in the installation embody the grotesque, where the boundaries between human and inanimate blur in unsettling ways.

Tanning’s work aligns with the horror genre’s exploration of the uncanny, a concept defined by Freud as the ‘disturbing familiarity’ of something simultaneously strange and recognisable. The hotel room, a typically mundane and neutral space, becomes a site of unease, where reality is destabilised, and the familiar turns frightening. In horror, this transformation of ordinary environments into settings of terror is a frequent motif - think haunted houses - where the safe spaces we rely on become corrupted by unknown forces. Tanning’s ability to evoke dread from a familiar setting mirrors the psychological horror that permeates classic ghost stories or surreal horror films, where the mundane is rendered menacing by its subtle alterations.

Furthermore, the bodily distortion present in Chambre 202 speaks directly to themes of body horror, where the human form is twisted and reshaped into grotesque, monstrous entities. Like in the works of David Cronenberg, where the body undergoes unsettling transformations, Tanning’s figures evoke a sense of bodily instability and fragility. These contorted forms reflect the grotesque’s fascination with hybridity, both consumed by and merged with their environment.

In examining horror's role within art, we see that it transcends mere shock and spectacle, instead serving as a profound means of engaging with our deepest fears, anxieties, and existential dilemmas. Whether through the grotesque distortion of the human form, the sublime confrontation with the unknown, or the monstrous embodiments of societal disorder, horror in art offers a unique lens through which we can explore the complexities of the human condition. By challenging conventional aesthetics and forcing viewers to confront the unsettling and the uncanny, artists working within this tradition invite us to reflect not only on our individual fears, but on the collective unease of the grotesque. Horror in art reveals beauty in the macabre and meaning in the monstrous, transforming explorations of the monstrous into a mirror of our innermost selves.