Does Art Lose Its Value When It Becomes a Trend?

Fight Aids Worldwide © Keith Haring 1990

Fight Aids Worldwide © Keith Haring 1990Market Reports

Key Takeaways

Art’s intersection with trends sparks a dynamic debate about its value and meaning in an age dominated by rapid cultural shifts and social media amplification. While trends can democratise art, they can risk reducing works to fleeting spectacles - the challenge is to balance the immediacy of digital engagement with the deeper resonance that makes art timeless.

Art has always held a dual role as both a cultural artefact and a commodity, reflecting the values, anxieties, and aspirations of the times. But in a world increasingly driven by social media and rapid trend cycles, we are compelled to ask: does art lose its inherent value when it becomes a trend? From Maurizio Cattelan’s controversial Comedian, to Yayoi Kusama’s Instagram-ready Infinity Rooms, the interplay between artistic value, cultural relevance, and market dynamics prompts questions surrounding how we perceive and assign value to art in the modern age.

The Cattelan Banana: When Art, Spectacle, and Absurdity Collide

Cattelan’s Comedian, a banana duct-taped to a wall, has transcended its humble materials to become a cultural and artistic flashpoint, emblematic of art as both spectacle and provocation. Debuting at Art Basel in 2019, the piece was an immediate sensation, prompting both admiration and ridicule as it questioned the boundaries of what constitutes art. Its initial sale for $120,000 was shocking enough, but by 2024, the absurdity of Comedian reached new heights, when cryptocurrency entrepreneur Justin Sun acquired the work for $6.2 million, and chose to eat the banana in a public spectacle. Sun’s performance blurred the line between destruction and re-creation, raising compelling questions about the very essence of the artwork. Was he dismantling its value or enhancing its message? After all, the banana was always intended to be replaced, a deliberate acknowledgment of its ephemerality. In consuming it, Sun underscored the transient nature of both trends and the art market’s obsession with spectacle, making himself part of the artwork’s ongoing narrative.

The lasting intrigue of Comedian lies in its ability to mock the art world while simultaneously embodying its most excessive tendencies. The piece forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about value and meaning in art. Are collectors buying an object, an idea, or the status that comes with ownership? Is the audience engaging with art, or merely with the spectacle surrounding it? These questions highlight Comedian’s dual identity as both critique and commodity, a work that thrives on its capacity to provoke conversation while remaining aggressively simple in its execution. By defying expectations and embracing absurdity, Comedian holds up a mirror to the art world and its spectators, challenging us to reconsider the foundations of artistic value in an age where the viral often supersedes the virtuosic.

While Comedian seems to embody the power of shock and viral trends to generate astronomical value, its roots stretch far deeper, connecting it to a legacy of conceptual disruption in art history. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a porcelain urinal turned upside down, signed “R. Mutt”, and submitted as art at the American Society of Independent Artists, fundamentally redefined the boundaries of artistic value. Duchamp’s radical proposal - that the artist’s intention alone could elevate a mundane object into art - challenged the primacy of craftsmanship and originality, giving rise to the concept of the “readymade”. Far from being a product solely of social media trends, Comedian taps into this longer legacy of art that shocks and challenges. Duchamp’s disruption paved the way for conceptual art, allowing Cattelan to build on these ideas in the modern era. By embracing absurdity and ephemerality, Cattelan not only critiques the commodification of art but also continues the dialogue Duchamp initiated over a century ago.

Image © Sotheby’s / Comedian © Maurizio Cattelan 2019

Image © Sotheby’s / Comedian © Maurizio Cattelan 2019Social Media: The Catalyst of Art Trends

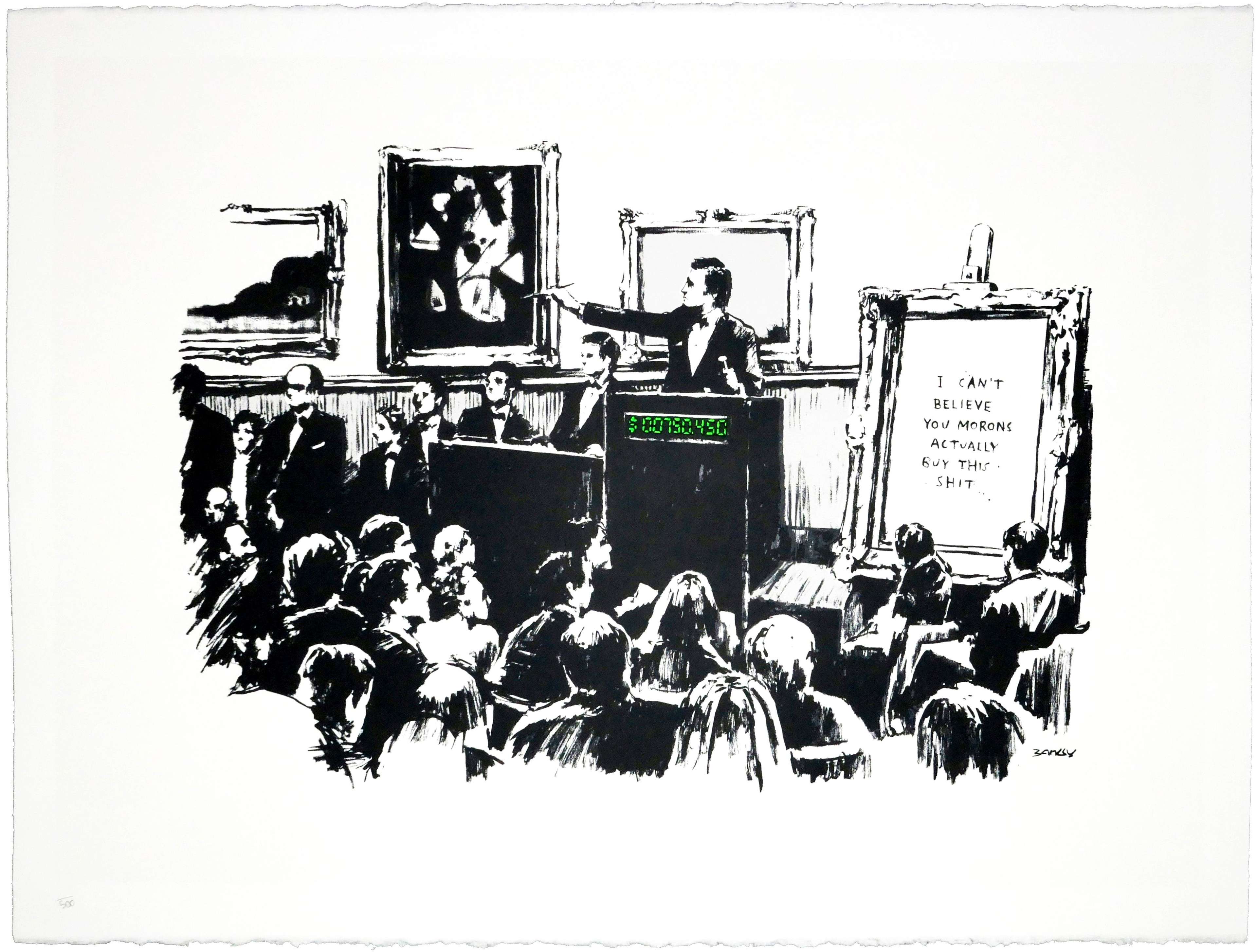

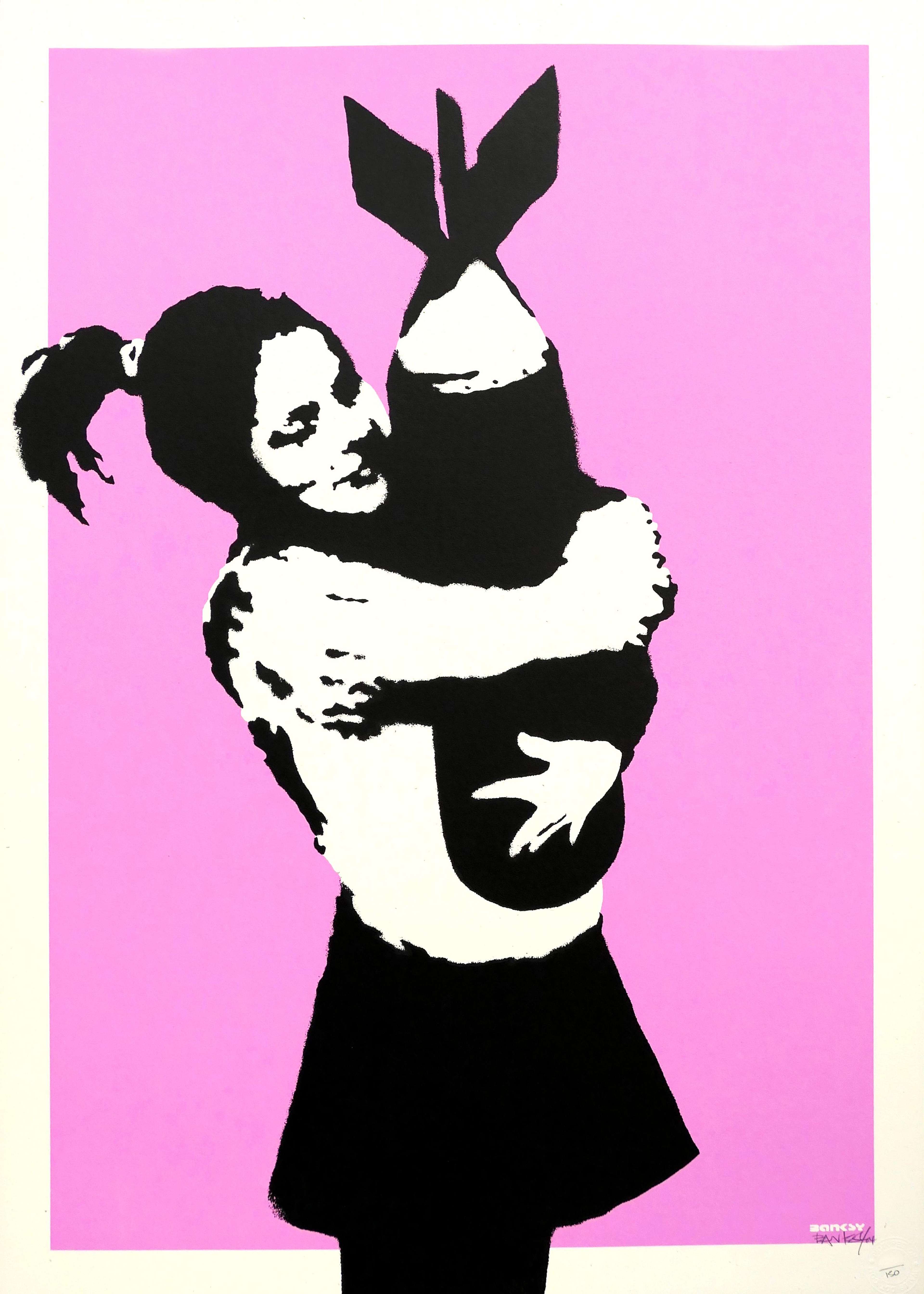

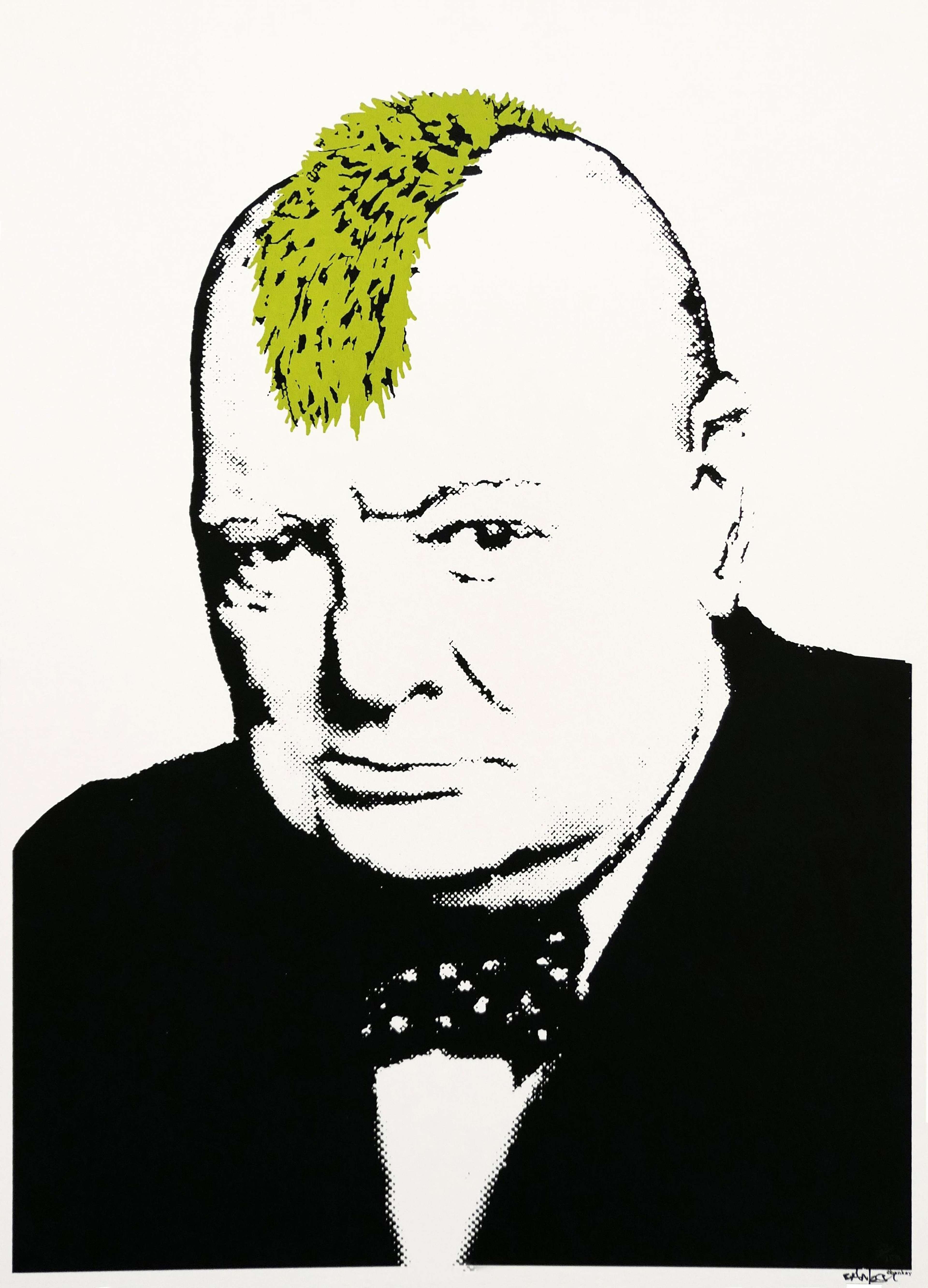

In the digital age, social media has emerged as the most influential arbiter of cultural trends, fundamentally reshaping how we discover, consume, and assign value to art. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok can serve as virtual galleries, curatorial tools, and marketing engines, collapsing the boundaries between artist, audience, and influencer. Banksy, a figure synonymous with subversive street art, demonstrates this dynamic powerfully. During his series of animal artworks in London, 2024, Banksy used Instagram to create a serialised narrative, posting a new piece daily for nine days without captions, and inviting millions to follow the unfolding story and deduce its meaning. This digital engagement turned ephemeral street art into a global phenomenon, blurring the line between the roles of artist and curator while raising questions about whether the immediacy of online validation compromises the novelty of his art.

Similarly, Kusama’s Infinity Rooms exemplify how art has become inextricably linked to its social media presence. These immersive installations, celebrated for their mesmerising interplay of light and mirrors, have been dubbed “Instagram traps,” drawing visitors willing to endure long lines for mere seconds inside the rooms. While Kusama’s work succeeds in introducing avant-garde concepts to broader audiences, the overwhelming emphasis on their photogenic appeal suggests they are transforming into digital commodities. When the primary motivation for engagement becomes the pursuit of the perfect selfie, the deeper conceptual underpinnings of Kusama’s work - such as her exploration of infinity, self-obliteration, and the sublime - can be overshadowed by the visual spectacle.

This phenomenon reveals a broader tension in the digital age; the capacity of social media to democratise access to art and ideas, contrasted with its tendency to privilege aesthetic consumption over thoughtful engagement. By prioritising what photographs well or trends quickly, platforms can inadvertently reduce complex works to fleeting digital experiences, or marginalise artworks that do not fit the current trends. Yet, at the same time, these tools also open the traditionally elitist artworld to a broader audience, challenge its exclusivity, and allow artists to connect with more diverse audiences. The question remains whether this new ecosystem enhances or diminishes the role of art as a vessel for reflection, critique, and emotional resonance.

Image © Flickr / The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) © Damien Hirst 2012

Image © Flickr / The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) © Damien Hirst 2012A Historical Perspective: Artists and Media Provocation

The commodification of art through spectacle is far from a new phenomenon, as the history of avant-garde art demonstrates. Duchamp’s Fountain radically redefined the boundaries of artistic practice, and provoked outrage and confusion, challenging conventional ideas about craftsmanship, aesthetics, and value. Similarly, Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) - a preserved tiger shark suspended in formaldehyde - continues to shock viewers not only for its provocative title and content, but for its sheer audacity. The work served as both an exploration of mortality and a commentary on the art world’s appetite for spectacle, proving that provocation and media attention have long been intertwined with artistic innovation.

Yet, these examples differ fundamentally from today’s spectacle-driven art in one crucial way: their impact was mediated through slower, more deliberate mechanisms of cultural dissemination. Duchamp and Hirst provoked debate that unfolded over years, giving audiences time to engage with their ideas. In contrast, the rise of social media has compressed the lifecycle of artistic trends, transforming them into ephemeral bursts of virality. Platforms like TikTok, with their algorithm-driven emphasis on quick, engaging content, prioritise instant gratification and rapid turnover. This shift accelerates the pace at which art enters and exits the cultural conversation, often reducing its complexity to surface-level appeal or meme-worthy moments.

For contemporary artists, this new reality creates both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, social media provides unprecedented access to global audiences, democratising exposure and allowing even the most unconventional works to find their niche. On the other hand, the relentless demand for spectacle risks diminishing the depth and longevity of engagement with art. Works designed to “go viral” may sacrifice the intellectual and emotional resonance needed to sustain their relevance over time, raising important questions about the balance between accessibility and substance.

Moreover, the pressure to produce content that captures attention within the confines of a fleeting trend cycle can dilute the critical or political potency of art. Where Duchamp’s Fountain provoked reflection on the institutional frameworks of art, and Hirst’s shark invited meditations on life and death, much of today’s trend-driven art risks being consumed as a fleeting image rather than a lasting idea. This is not to say that all contemporary art lacks depth, but rather that the current media environment often limits the space for sustained engagement and nuanced interpretation.

The commodification of art through spectacle has always been a balancing act between provocation and profundity. The question now is whether the accelerated tempo of the digital age enriches or erodes that balance, and how artists can navigate a landscape where the demands for relevance and resonance increasingly collide.

Image © Pixabay / A crowd of people taking pictures of the Mona Lisa © 2000 - 2016

Image © Pixabay / A crowd of people taking pictures of the Mona Lisa © 2000 - 2016Trendy vs. Timeless

Art’s relationship with trends highlights a vital distinction between the trendy and the timeless - a dichotomy central to understanding how art gains and retains value. Trend-driven works like Cattelan’s Comedian, or the explosive rise of NFTs, often capture the zeitgeist through novelty, spectacle, or technological innovation. These pieces command attention in their moment, fueled by media and market fascination, but they sometimes lack the resonance required to endure.

Yet, when art becomes a trend, it also tends to experience an exponential surge in market value, as demonstrated by Banksy’s Love Is In The Bin. Originally titled Girl With A Balloon, the artwork famously shredded itself immediately after being auctioned for $1.4 million in 2018. The viral stunt transformed it into a cultural sensation, and when it reappeared on the auction block in 2021, it sold for a staggering $25.4 million - more than 18 times its original value. This dramatic escalation underscores how art tied to a trend can evolve into a high-stakes commodity, with its cultural and financial worth amplified by the spectacle surrounding it. By contrast, universally popular works, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, retain their value not just through their notoriety, but through their sustained artistic, cultural, and historical significance. The Mona Lisa has transcended centuries of shifting tastes to remain an icon, a testament to its enduring ability to provoke curiosity and admiration.

However, the line between trendy and timeless is more fluid than it may first appear. Consider Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998), an installation that shocked audiences in 1998 with its unflinchingly confessional depiction of a lived-in bed, surrounded by intimate detritus. Initially dismissed as sensationalist and provocative, My Bed has since undergone a reevaluation, celebrated for its vulnerability and for challenging traditional notions of artistic subject matter. When it sold at Christie’s for £2.5 million in 2014, it had crossed the boundary from controversial trend to recognised milestone in contemporary art. This evolution suggests that art that is marshalled into the category of “trendy” can achieve lasting significance if it resonates deeply on emotional, intellectual, or cultural levels.

The enduring challenge for artists and audiences alike is to identify works that balance immediate relevance with deeper conceptual, emotional, or aesthetic significance. A piece that appears trendy, like My Bed, gains timeless stature if it can transcend its moment and contributes meaningfully to the evolving dialogue of art. Conversely, even works heralded as classics must continually justify their status by remaining compelling to new generations. The interplay between trend and timelessness is thus not a binary but a spectrum, shaped by how we interpret and re-interpret art through the lens of history and changing cultural values.

The Double-Edged Sword of Trends

Art trends are not inherently detrimental; in fact, they can play a pivotal role in reshaping the cultural landscape by democratising access to art and expanding its reach - Kusama’s meteoric rise as a social media icon exemplifies this. Similarly, TikTok has emerged as a powerful platform for emerging artists, allowing creators from diverse backgrounds to showcase their work to a global audience, bypassing traditional gatekeepers of the art world. These platforms offer opportunities for representation, visibility, and inclusion that were once unimaginable, transforming art into a more participatory and accessible cultural force.

However, this democratisation comes with significant trade-offs. Trends often prioritise spectacle over substance, reducing works to easily consumable digital artifacts. Pieces like Cattelan’s Comedian, with its viral simplicity of a banana duct-taped to a wall, highlight how the art world can become fixated on the novelty and shock value that drive virality. While such works provoke conversation, they risk overshadowing pieces with deeper emotional, or aesthetic resonance. This trend-driven approach can skew the art market, elevating works that thrive on social media algorithms while marginalising those that demand slower, more contemplative engagement. As a result, the metrics of “likes” and “shares” can inadvertently become proxies for artistic value, commodifying art in ways that reduce it to mere content.

This creates a paradox; trends have the potential to elevate art to unprecedented levels of visibility, drawing in audiences who might otherwise remain disengaged, yet they can also diminish art's integrity by emphasising ephemeral appeal over enduring significance. In this context, Kusama’s Infinity Rooms might be seen not as immersive meditations on infinity and self-obliteration, but as backdrops for selfies - a transformation that risks reducing their conceptual depth. Similarly, TikTok’s short-form format, while democratising, often compresses artistic narratives into moments that prioritise immediacy over nuance.

Yet trends are not universally shallow or fleeting. They can serve as entry points into the art world, sparking curiosity and deeper engagement. Even works like Comedian, despite their controversial simplicity, open up valuable debates about the nature of value, originality, and the role of spectacle in contemporary art.

Can Art Exist Without Social Media?

In an age where social media plays a dominant role in shaping cultural narratives, it’s easy to forget that art’s power to provoke, inspire, and endure predates the digital era. Consider Marcel Broodthaers’ Pot of Mussels (1968), a conceptual piece that juxtaposed ordinary mussel shells with commentary on consumerism and absurdity. Long before hashtags and viral algorithms, Broodthaers managed to challenge conventional ideas of artistic value and meaning, sparking debates that continue to resonate. Such works remind us that art’s impact has historically been rooted in its ability to disrupt norms, engage audiences on an intellectual level, and reflect the complexities of its time - qualities that do not inherently require the amplification of social media.

The historical context suggests that art does not require social media to thrive; the key difference today is the speed and scale at which art can disseminate - social media has simply added a new dimension to its reach and reception. Before the internet, movements like Dada, Surrealism, and Pop Art achieved global resonance through exhibitions, manifestos, and media provocations, all without the instantaneous connectivity of the digital realm. Salvador Dalí’s surrealist dreamscapes, Andy Warhol’s explorations of consumer culture, and even Duchamp’s “readymades” became touchstones of modern art by challenging their audiences to think critically rather than passively consume.

Ultimately, art’s existence and relevance are not contingent on social media, but its current cultural position is undoubtedly shaped by it. Whether this influence enriches or impoverishes the art world depends on how artists, curators, and audiences balance the platform’s reach with the qualities of nuance, complexity, and reflection.

Art’s Value in the Age of Trends

Art does not lose its value when it becomes a trend, but it risks losing its meaning when reduced to a trend alone. Art’s value has always been multifaceted, rooted in its ability to provoke, inspire, and connect with audiences across generations. While the rise of social media and trend-driven cycles has accelerated the pace at which art is consumed and commodified, it has not fundamentally changed what makes art meaningful. Works like Comedian highlight the tension between spectacle and substance, forcing us to confront the art world’s appetite for novelty while tapping into a legacy of conceptual disruption that precedes the digital age. Trends are a double-edged sword - they democratise art, but they also risk prioritising surface appeal over deeper resonance. Yet, history shows us that art’s true power lies not in fleeting moments of virality, but in its capacity to reflect and challenge the complexities of its time. Whether mediated by hashtags or exhibitions, the most enduring works transcend their moment, bridging the gap between the trendy and the timeless.