Behind the Red Dots

(Poster) January 16 © Roy Lichtenstein 1994

(Poster) January 16 © Roy Lichtenstein 1994Market Reports

MyArtBroker’s Authentication Expert & Managing Director discuss the perils of pricing, or the lack thereof, and how to invest like an insider.

A Common Gallery Scenario: The Elusive Price List

We’ve all been there. You walk into an established gallery in New York, London, or Paris to view an exhibition. Chances are you’re not really interested in buying anything. But you’re still curious about how much the paintings cost. You approach the front desk in search of a price list. When you discover there isn’t one, you ask the employee seated behind the desk, “May I see a price list?” In a perfect world (or a world other than the art world), you would be handed a sheet of paper which lists the exhibition’s paintings and their corresponding prices, with red dot stickers affixed next to those works which were already purchased. Instead, the front desk attendant responds with a monotonous relish, “They’re all sold — there is no price list.”

Whether every picture is spoken for is beside the point. What matters is that you were just humiliated. Hopefully, you learned your lesson and would never commit this transgression again. As you exit the gallery, you’re left to wonder what the big deal was about knowing the cost of the pictures on display. How on earth could this create a problem for the artist’s market or the gallery?

Most blue chip galleries insist that guarding the cost of each work is a necessary discretion designed to protect an artist’s market. The theory is that if word got out that, for example, Jasper Johns’s price list revealed a few paintings without red dots, it might impact his market in a negative way. With that in mind, it makes sense to create the illusion that his works are so desirable, and in such heavy demand, that it’s almost impossible to buy one. And you do so by insisting nothing is for sale.

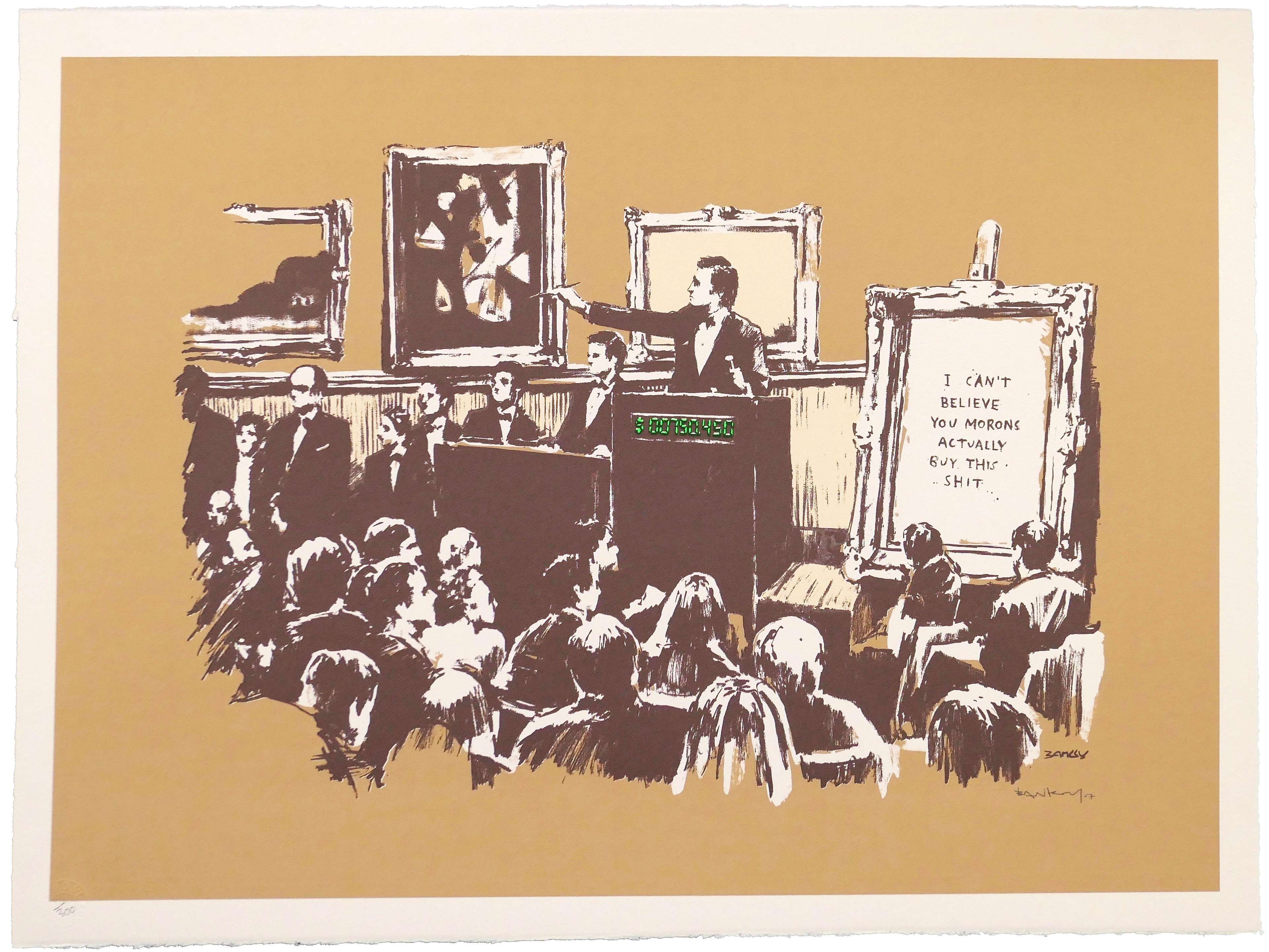

Auction Tactics: Low Estimates & High Demand

In the secondary market, but particularly at auction there are similar traits - the setting of a presale estimate at auction is not there to inform you of its actual price, they are there to provoke intrigue. Good news for seller’s you’d expect, but auction house valuations have a few strategic angles that are equally as opaque as the ‘Everything is sold’ approach of blue-chip galleries, and play just as much with the concept of ‘demand’. When an auction house consigns a work, they have a vested interest in setting the reserve as low as the seller dares for two reasons: They can start the bidding low, and drive up the price. This is tactical - a low estimate means more people register to bid, and the more bids that pile on top of the work at the sale, the more the work has the appearance of being in high demand, driving the bidders' motivation on and on. Secondly, the low reserve ensures auction houses meet their most important metric: sell-through rate. And perhaps thirdly - what would be the fun of the estimate being a fixed price, the vendor knowing exactly how much they’d return, the bidder knowing exactly what they’re in for? Everyone likes surprises right? Wrong: and the MyArtBroker algorithm has been created to solve this dilemma displaying data that blends true value with several other factors that seek to actually predict the price of the work in real time. More on that here.

The market has been through this - during the late 1980s, the New York Department of Consumer Affairs thought they could solve this at least with the galleries and decided that enough was enough. Just like any other business, galleries were required to display their price lists in a conspicuous place — without anyone having to humble themselves by asking to see one. The Commissioner of Consumer Affairs, Angelo J. Aponte, said the action would let consumers know, “what their purchases will buy them without being subject to the vagaries of mystery, theater and snobbery.”

The Brief Era of Enforced Transparency in the Art Market

Initially, galleries complied including the Mary Boone Gallery, one of the most intimidating in New York. There was a flurry of enforcement and a handful of fines were issued, including several to Ronald Feldman Fine Arts (one of Andy Warhol’s print publishers). But within a year, the price lists grew elusive and eventually disappeared entirely. Before long it was business as usual and gallery goers once again found themselves genuflecting at the front desk.

The Strategy Behind Secrecy: Creating Value in Art

With that in mind, over the years the gallery and auction network has evolved a set of strategies that it believes are necessary to flourish. The basic idea is to create an illusion that the artists you represent are destined for big things. If you market them properly, and get a few good breaks, one or two may make it into the art history books. And equally important, might be featured in an evening sale at Sotheby’s or Christie’s.

The MyArtBroker Approach: Transparency & Data-Driven Valuation

At MyArtBroker, we built our algorithm to do one thing better than anyone else: tell you what a print is really worth - instantly, transparently, and with the full story. It powers MyPortfolio and the Trading Floor, and drives the live value indicators you see on artwork pages, which shows demand before the theoretical auction starts for complete transparency into live buy/sell interest - answering “How much is this artwork?” as thoroughly as possible. The engine draws on data from 400+ auction houses (including unsold lots, hammer prices and last bids), integrates private-sale intelligence that never appears in auction results, and responds to real collector demand so valuations reflect where the market is heading, not just where it’s been. Because print markets are nuanced, it understands variants - colourways, paper types and proof states (APs, PPs, TPs, sets) - and it values each work in the context of its wider series to avoid mismatched comparables. This is the first valuation engine built specifically for prints & editions, and it’s the engine behind everything we do: Instant Valuation gives you a fast, algorithm-only benchmark in seconds, while Expert Valuation layers specialist judgement for unusual condition, provenance or rare proofs. Combined, you get a precise, evidence-based range and the confidence to act when the time is right - powered by people, backed by data.

A Revolutionary Approach to Art Valuation

Buying on the primary market is always going to be impossible to navigate, and you can always fall back on buying what you love, but buying with an asset mindset is frankly futile.

You yourself are going to have to put the work in developing their careers. At an artist’s first show, the gallery intentionally prices the works slightly below what the market will bear. Assuming the exhibition sells out, they then raise the prices at the next show — thus making the first round of buyers feel good about their purchases, and the next onto a good thing. If the artist and the gallery have the right connections, you might roll the dice and try and place a painting into the next round of auctions. If the artist’s supporters get involved and bid the painting up to a price that exceeds expectations, then you’ve created a buzz that the artist is in play — and you’re off to the races. It happens, but buying on the secondary market you have a few more tools, but you need to know where to look.

Empowering Art Collectors with Comprehensive Market Data

For ‘wet paint’ artists, when an artist is deemed investment worthy, a dealer tries to do everything within their power to keep the momentum going. One of the ways you do that is by making sure that every new painting is spoken for. By the time the artist’s next show rolls around they need to pre-sell every work (even if they have to buy them as stock). Then, when the show opens, one can avoid the price list controversy by simply putting it on the front desk — awash in a sea of red dots.

Obviously, there’s more to promoting an artist than what’s mentioned above. There’s an absurd amount of expenses, not the least of which include exhibiting the work at an ever-growing circuit of international art fairs. But like marketing any luxury good, whether an elite watch or a blue-chip painting, it’s all about creating an illusion of scarcity and desirability.

About the Authors

Richard Polsky has spent his life as a dealer and authenticator of American Pop Art — www.RichardPolskyart.com — authenticates the work of seven artists: Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Jackson Pollock, Roy Lichtenstein, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Bill Traylor.

Charlotte Stewart spent 15 years in auction and private collections, before joining MyArtBroker in 2019.