I Authenticated Andy Warhol: Welcome To My Nightmare

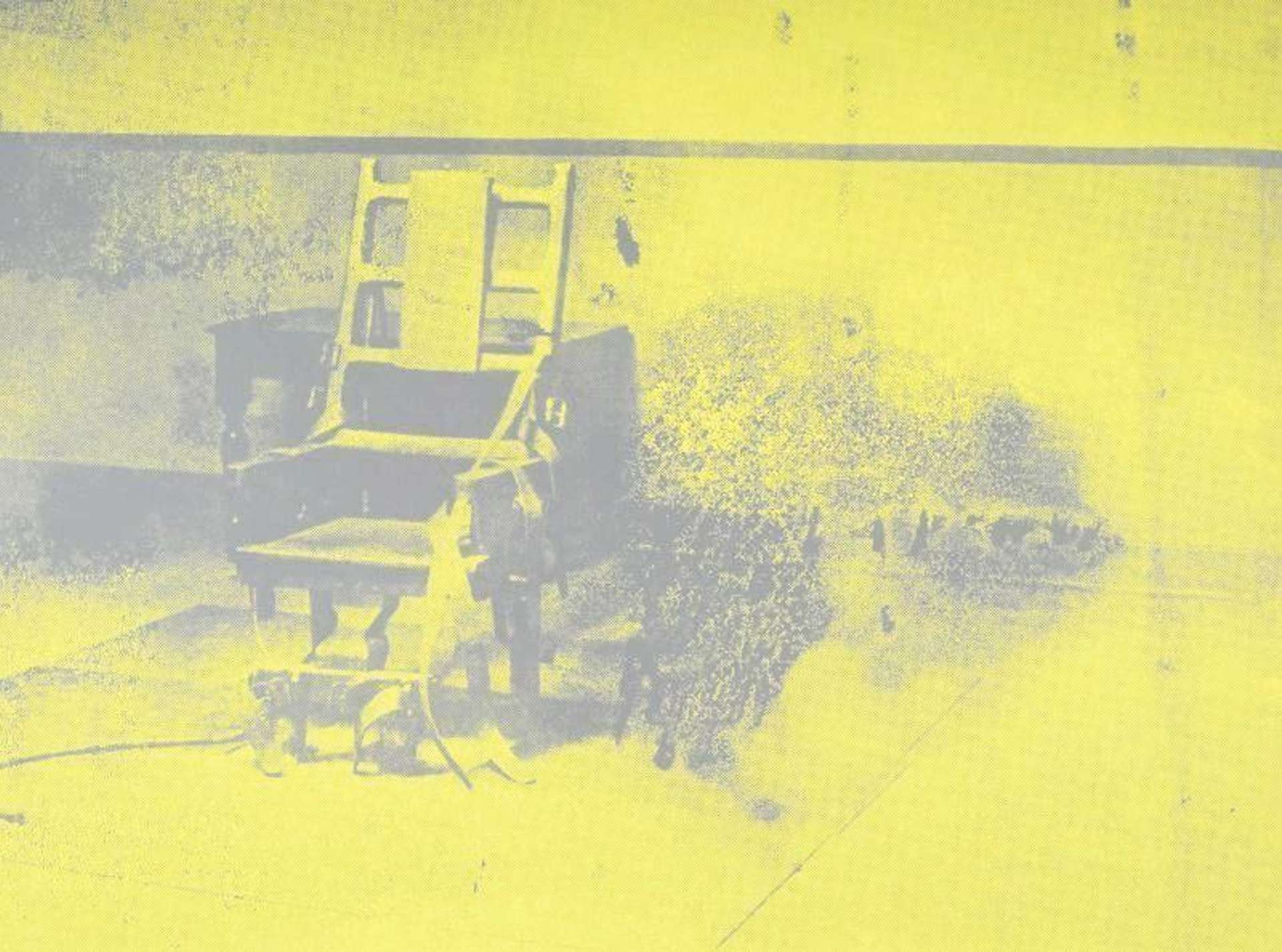

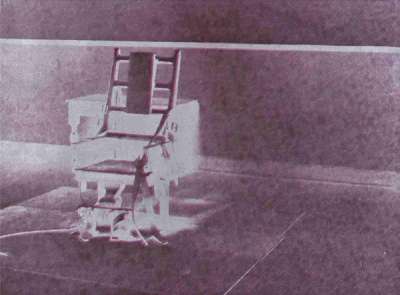

Electric Chair (F & S 11.78) © Andy Warhol 1971

Electric Chair (F & S 11.78) © Andy Warhol 1971MyPortfolio

Read Chapter Two of Richard Polsky’s exclusive mini series on the world of Andy Warhol authentication.

Chapter Two

During the 1970s, as rock journalism transitioned into a serious endeavor, there were three magazines which covered the nascent rock scene: Rolling Stone, Creem, and Circus. Rolling Stone was the gold standard. But, at least for a short period, Creem and Circus were players.

Shep Gordon had learned of an issue of Circus that featured a cover story titled, “Alice Cooper Beats the Devil,” which allegedly included a photograph of the red Little Electric Chair. I hoped it would verify that Alice owned his Warhol at least since the mid-1970s. Fortunately, I was able to find a copy on eBay. The story was chock full of bizarre pictures, including one of live tarantulas crawling all over a screaming Alice. But I failed to spot an illustration of the Warhol. Then I came to the sentence, “In Coop’s living room, next to a poster of Alice waving something bloody (the only artifact in his house of his stage show) hangs an Andy Warhol print of a solitary electric chair.” Bingo.

Still, I wanted further verification. Using his rock world connections, Shep Gordon discovered that the article’s author, Steve Rubenstein, currently worked at my hometown newspaper, The San Francisco Chronicle. I gave him a call and asked if he remembered conducting the interview with Alice. He hesitated before responding, “I remember meeting Alice — who was very nice — but I have no idea what was hanging on his walls.”

“You’re sure you don’t recall seeing a Warhol?” I asked, leading the witness.

“No — I don’t remember seeing it. That was over forty years ago!”

I slumped in my chair but then perked up when Steve added, “But I can tell you this — if I wrote it, then it’s true!”

I began to think about Alice Cooper. My thoughts drifted back to 1972, when Alice received the Little Electric Chair as a gift. At the time, I was a junior in high school living in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio — and Alice Cooper was already an international superstar. I’m Eighteen, School’s Out, and No More Mr. Nice Guy topped the charts. It had already been two years since the Beatles disbanded. The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin were at the peak of their popularity. Yet, a softer sound led by Crosby Stills & Nash, the Eagles, and James Taylor was being ushered in. And then there was Alice.

Alice Cooper’s reputation was as much about shocking the audience as the music itself. However, the more successful Alice became, the less outrageous he seemed. After a while, he almost felt mainstream. Parents no longer loathed him. Still, his fans continued to demand his unique brand of theatrics. What they got were wild costumes, ghoulish makeup, live boa constrictors… and an electric chair. When Alice began to use a fake electric chair as a stage prop — and proceeded to “electrocute” himself during the show — few made the connection between him and Andy Warhol.

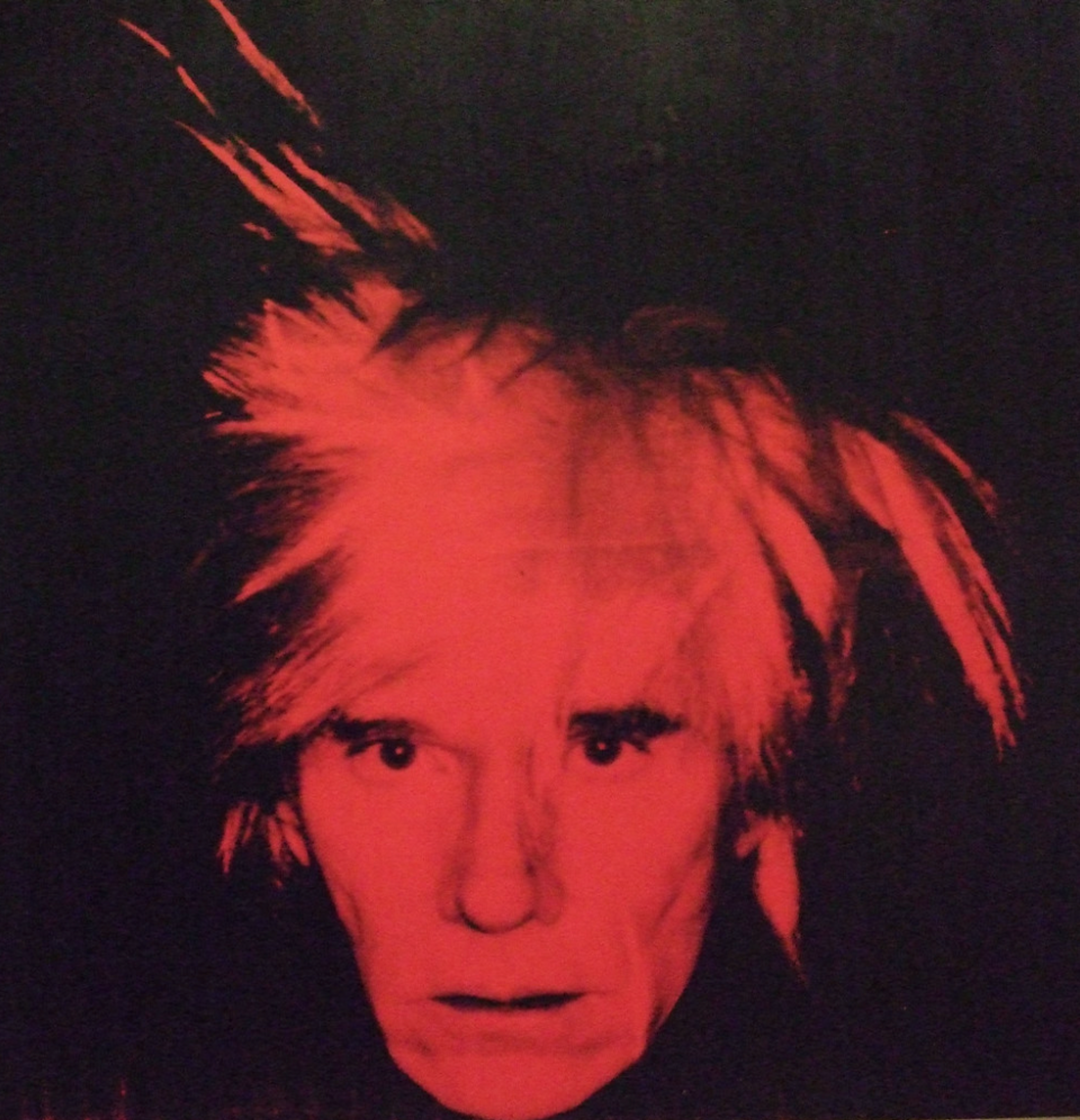

By 1972, Alice’s savvy management team, led by Shep Gordon, had broken his act into the big leagues. Though the rock industry was far from the corporate titan it would become, the money was pouring in. When Alice’s girlfriend Cindy Lang approached Shep for a $2,500 loan, to buy him a birthday present, he was more than comfortable granting it. At the time, Warhol’s Factory was undergoing profound changes. Only four years earlier, he had been shot by a deranged groupie named Valerie Solanas, and came perilously close to dying. The sad thing was that his work, which had been something akin to genius, would never be the same. Andy Warhol lost his edge. With only a couple of fleeting exceptions — the Maos (1972-73) and the Fright Wig Self-Portraits (1986) — the spark was gone.

Image ⓒ Jim Linwood / Self-Portrait ⓒ Andy Warhol 1986

Image ⓒ Jim Linwood / Self-Portrait ⓒ Andy Warhol 1986The original Factory was a well-known gathering spot for creative types and social misfits. The media sensationalized the Velvet Underground, the Warhol-dubbed “Superstars,” and the outrageous parties that brought together celebrities and drag queens. But within a few years, the Factory disintegrated to a point where even Ivan Karp, the art dealer who discovered Andy, refused to go there anymore. As Ivan put it, “I found the whole scene gloomy.”

Little is known about the early business practices of Warhol’s studio. Basically, there was no management. Paul Morrissey, who directed Warhol’s experimental films, nominally took charge when someone wanted to buy something. The problem was there was a lot of cash-and-carry and little recordkeeping. Warhol also traded paintings for services — with the deals only vaguely recorded. For example, his lawyer from the 1960s, Si Litvinoff, handed Andy a bill and was literally told, “There’s a pile of unstretched canvases over there — pick out what you want.” Mr. Litvinoff proceeded to help himself to a Flowers painting, an extremely valuable silver Marlon (Brando), and a few others. To this day, we still don’t know the identities of those “few others.”

Meeting Andy Warhol's business manager, Fred Hughes

By the time Cindy Lang showed up to buy a painting, Andy Warhol had brought in the dapper Fred Hughes as his first official business manager. He had met Hughes a few years earlier through Jean and Dominque de Menil, the pace-setting art patrons from Houston, who would go on to form the amazing Menil Collection — which became a pilgrimage for art lovers. In 1969, they founded the Institute for the Arts at Rice, and had taken the young Fred Hughes under their wing. Andy was visiting the de Menils when he was introduced to Hughes. As the expression goes, it was kismet. Fred and Andy connected, one thing led to another, and the next thing you knew Hughes was on a plane to New York to work with Andy.

Fred Hughes quickly brought his organizational skills to bear. He kicked out all of the edgy characters who were part of the Factory’s ambiance but contributed little to its productivity. Next, he cleared out a room, purchased some elegant antique furniture, and turned it into a professional looking office. When someone wanted to buy a painting or propose a show, they had to pass muster with Fred. He then focused on ways to increase Andy’s income. Fred looked into traditional investments, including stocks and real estate. He also forged relationships with Europe’s leading dealers like Bruno Bischofberger and later his protégé Thomas Ammann. Mr. Ammann’s would go on to acquire Shot Sage Blue Marilyn — estimated to be worth $200 million prior to its sale at Christie’s in 2022. Seeking to diversify, Hughes helped convince Andy to start Interview magazine which increased his celebrity profile, led to lucrative portrait commissions, and was also a money maker.

Years later, in 1986, I met Fred Hughes for the first and only time. I had made an appointment with him to buy an Andy Warhol “Dollar Sign” painting for a Warhol show I was putting together for my San Francisco gallery, Acme Art. I’ll never forget Fred Hughes’s sophisticated taste. He wore a beautifully tailored suit and resembled an English lord. But what really stood out was the way he wore his wristwatch over the cuff of his white shirt. Now, that was style.

Image © Christie's / Shot Sage Blue Marilyn © Andy Warhol 1964

Image © Christie's / Shot Sage Blue Marilyn © Andy Warhol 1964Cindy Lang visits the Factory in 1972

Andy and Fred grew close. Soon, he realized he could trust Fred with everything. This freed Andy to make art full-time. In 1972, Warhol began his great Mao series, which portrayed the communist leader of the most populous nation on Earth. Richard Nixon had just opened a dialogue with China — which was considered remarkable at the time. Andy seized the zeitgeist; his creative muse returned. The Maos became his first series to incorporate hand-painting on top of a screened image. When a collector hung a Mao in his home, he was performing both a subversive and decorative act. Andy Warhol was back — at least for now.

This was the setting when Cindy Lang arrived at the Factory to buy Alice a gift for this 24th birthday. Her friends there were more than happy to accommodate her — especially when they saw she had money to spend. She asked to see some Little Electric Chairs; there were plenty to choose from. As previously mentioned, there was little demand for these paintings. Most collectors preferred works from the Celebrities series: Marilyn (Monroe), Elvis (Presley), and Liz (Taylor).

How much is Andy Warhol's signature worth?

We don’t know the names of the individuals who Cindy Lang worked with that day at the Factory. We assume that Fred Hughes wasn’t there. That’s because there was no paperwork on the purchase. We also assume that Andy Warhol wasn’t present either because the painting was never signed. The matter of his signature is complicated. Long ago, Andy established a studio policy to not sign paintings until they were sold or sent out for exhibition. He did this to cut down on theft. This was a real problem, given the endless stream of visitors who descended on his space. People thought nothing of fishing discarded small canvases out of the trash. Or worse, actually swiping finished pictures leaning against the wall.

Andy’s original approach to signing paintings drove future collectors to distraction. Part of his philosophy was that he wanted to turn himself into a “machine.” That’s to say he tried to detach himself and remove the artist’s touch. This is what led to his first photosilkscreen paintings, where he used a commercial mechanical process to make fine art. Andy encouraged others to sign his paintings for him, including his assistants. He even asked his mother, Julia Warhola, to sign canvases. Ivan Karp once told me about the surreal experience of signing Andy’s paintings.

Since Andy messed around with how his works were signed, his signature became less important than that of any other major artist. In general, the signature is considered the confirming act which makes a work genuine. While most collectors would prefer a signed Warhol over an unsigned one, a signature has never been crucial in determining authenticity. To make matters even more complicated, when Andy Warhol died approximately 4,000 unsigned paintings remained in the estate. When one was sold, a small blue ink rubber estate stamp was affixed to the back. Adding yet another layer of complexity, before the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board was formed, Fred Hughes handled authentication duties — his signature can be seen on the verso of some paintings.

When Cindy Lang left the Factory that day, she probably was told they’d have Andy sign her painting the next time he saw Alice. But who knows. Cindy walked out of there with the red sheet of canvas rolled up in a heavy cardboard shipping tube. Alice was thrilled by Cindy’s gift. But it took him awhile to hang it; he was too busy touring. The red Little Electric Chair was soon relegated to its circular cardboard home again — where it remained for another four years.

During the early 1970s, the art world and the rock world were expanding. Not to overly romanticize the era, but it was a heady moment where key figures from both worlds spent time together. Predictably, Andy Warhol was at the center of it all. He functioned liked a lodestone, pulling a diverse cast of characters into his orbit.

If you read Patti Smith’s book, Just Kids, she talks about how important Warhol was to her formation as an artist and musician. To be able to walk into Max’s Kansas City and sit at Andy’s table meant everything to her. If you were a young person who made your way to New York, in search of direction for your career in the arts, just showing up was the key. If you did your homework and were respectful, you could meet everyone. Shep Gordon once commented, “Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Jim Morrison were well-known but they weren’t Mount Rushmore yet.” That would come later.

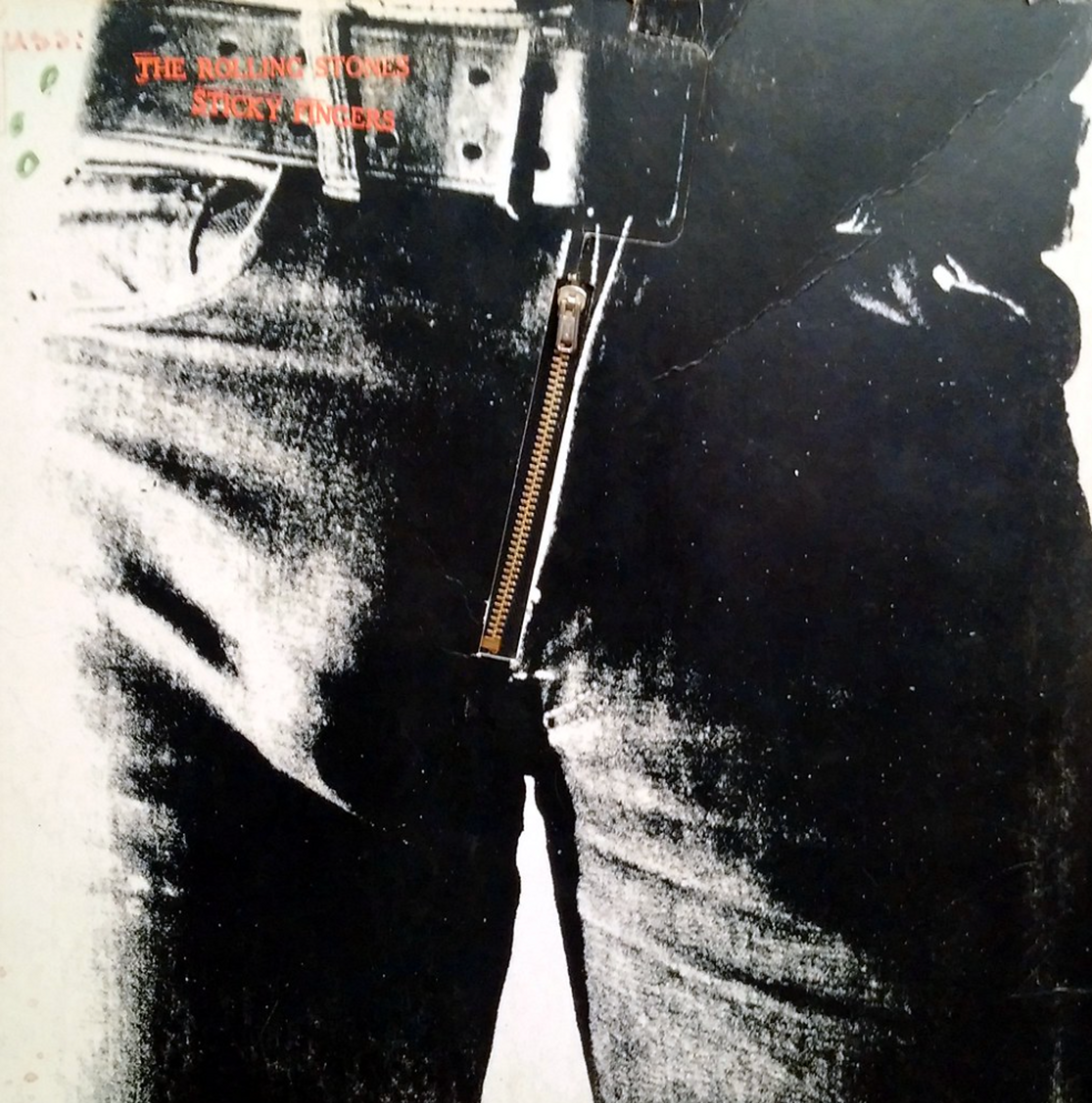

Where Andy’s influence found its greatest mark was with musicians who were already famous — and no group (other than the Beatles) was more famous than the Rolling Stones. In 1964, Andy forged a relationship with Mick Jagger, during the Stones first American tour. You sensed from day one their relationship was destined to be transactional. There was always a bit of tension because Andy was known for using people and Mick was wary of being used. The friendship started out slowly, then built steam when Mick — possibly influenced by hipster sixties British art dealer Robert Fraser — got in touch with Andy to design the album cover for Sticky Fingers (1971). Mick sent Andy a telegram offering suggestions for what he was looking for. At the bottom of the note, he wrote: “In my short sweet life I’ve noticed the more complicated the design, the more fucked up it gets. But with that in mind, I leave this in your capable hands.”

As a successful commercial illustrator early in his career, Warhol had already designed a number of record covers. His “peel here” yellow banana cover for the Velvet Underground’s first album remains a high-water mark for the genre. For the Stones commission, Warhol came up with the brilliant idea of having an actual metal zipper glued into a pair of jeans reproduced on the cardboard cover.

Image ⓒ Logos: The Art of Photography / The Rolling Stones' "Sticky Fingers" Album Cover ⓒ Andy Warhol

Image ⓒ Logos: The Art of Photography / The Rolling Stones' "Sticky Fingers" Album Cover ⓒ Andy WarholAndy Warhol and the Stars of the Century

Upon its completion, a delighted Mick said, “I thought that the album cover he did for the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers was one of the most original, sexy and amusing packages that I have ever been involved with.” We don’t know for certain how many albums Warhol’s witty design helped the Stones sell, but it didn’t hurt. Sticky Fingers remains one of the Rolling Stones’s biggest selling albums and Andy’s contribution has become inseparable from its myth.

The success of the Sticky Fingers experiment drew Andy Warhol and Mick Jagger closer together. Though David Bowie wrote a clever song, called Andy Warhol — “He’ll think about paint and he’ll think about glue what a jolly boring thing to do” — Andy never painted his portrait. That honor was reserved for Mick. In 1975, Warhol screened a series of eight 40” x 40” portraits of the Stones front man. They were accompanied by a portfolio of ten different colorserigraphs of Mick, produced in an edition of 250, with each print signed by Andy Warhol and Mick Jagger. The publisher probably sold as many to rock memorabilia collectors as to collectors of fine art.

1975 was also a big year for Alice Cooper; he met Sheryl Goddard. She was a dancer in his “Welcome to My Nightmare” tour. By 1976, they were married — and have stayed married to this day — which says a lot about Alice’s character. That period in his life also marked the re-emergence of the red Little Electric Chair from storage. At this point, Alice and Sheryl had no idea what they were sitting on. During the 1970s, Andy Warhol was viewed largely as a curiosity in America, rather than a serious artist (Europe took a more enlightened view). When Alice finally got around to hanging his Warhol — which was mentioned for the first time in print in the Circus magazine interview — the painting would embark on a journey that would add to the growing legend of Andy Warhol.

Keep reading: 'I Authenticated Andy Warhol'.

Read the previous instalment of the series here.

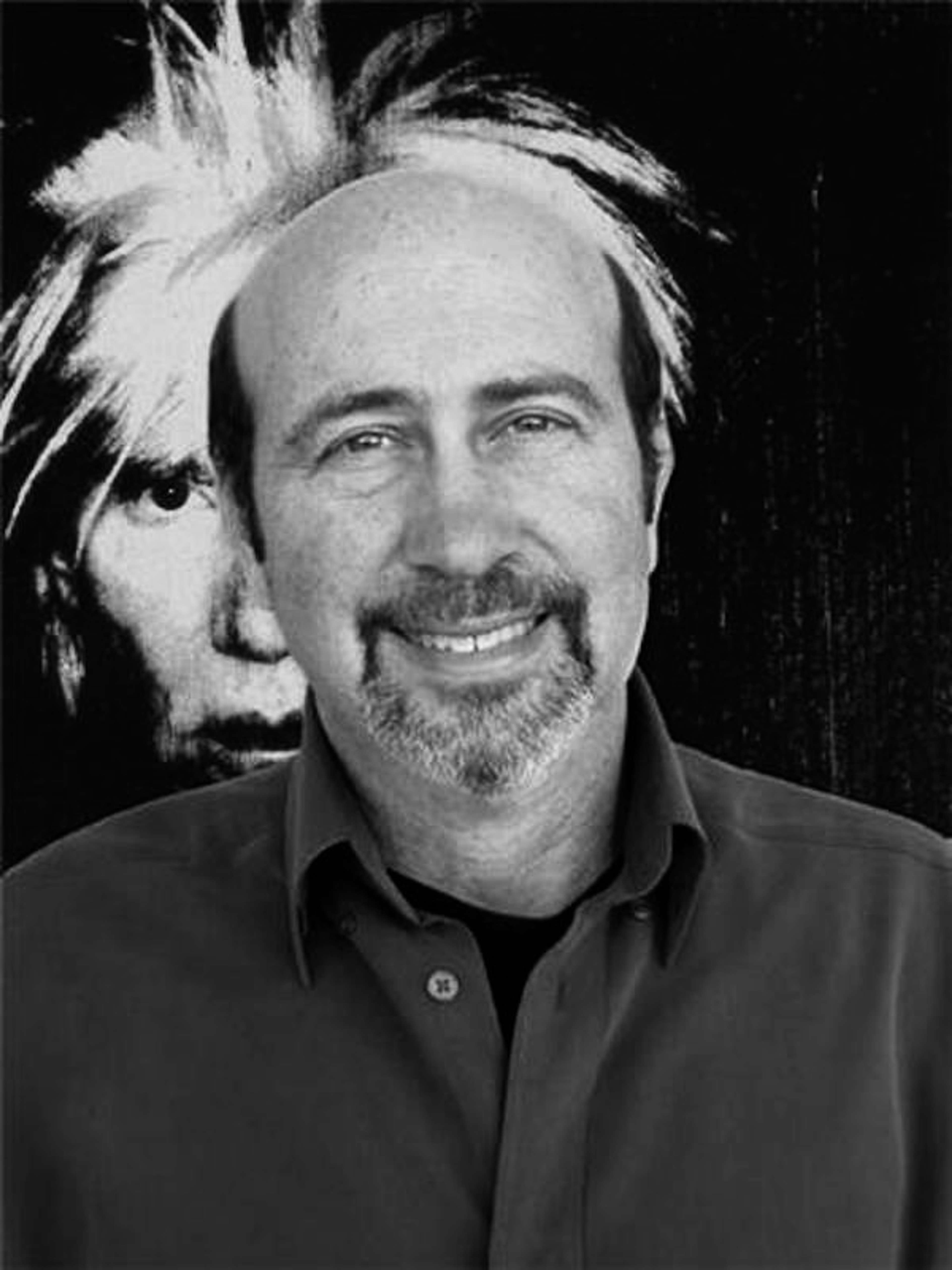

Richard Polsky is the author of I Bought Andy Warhol and I Sold Andy Warhol (too soon). He currently runs Richard Polsky Art Authentication: www.RichardPolskyart.com