I Authenticated Andy Warhol: The Scottsdale Connection

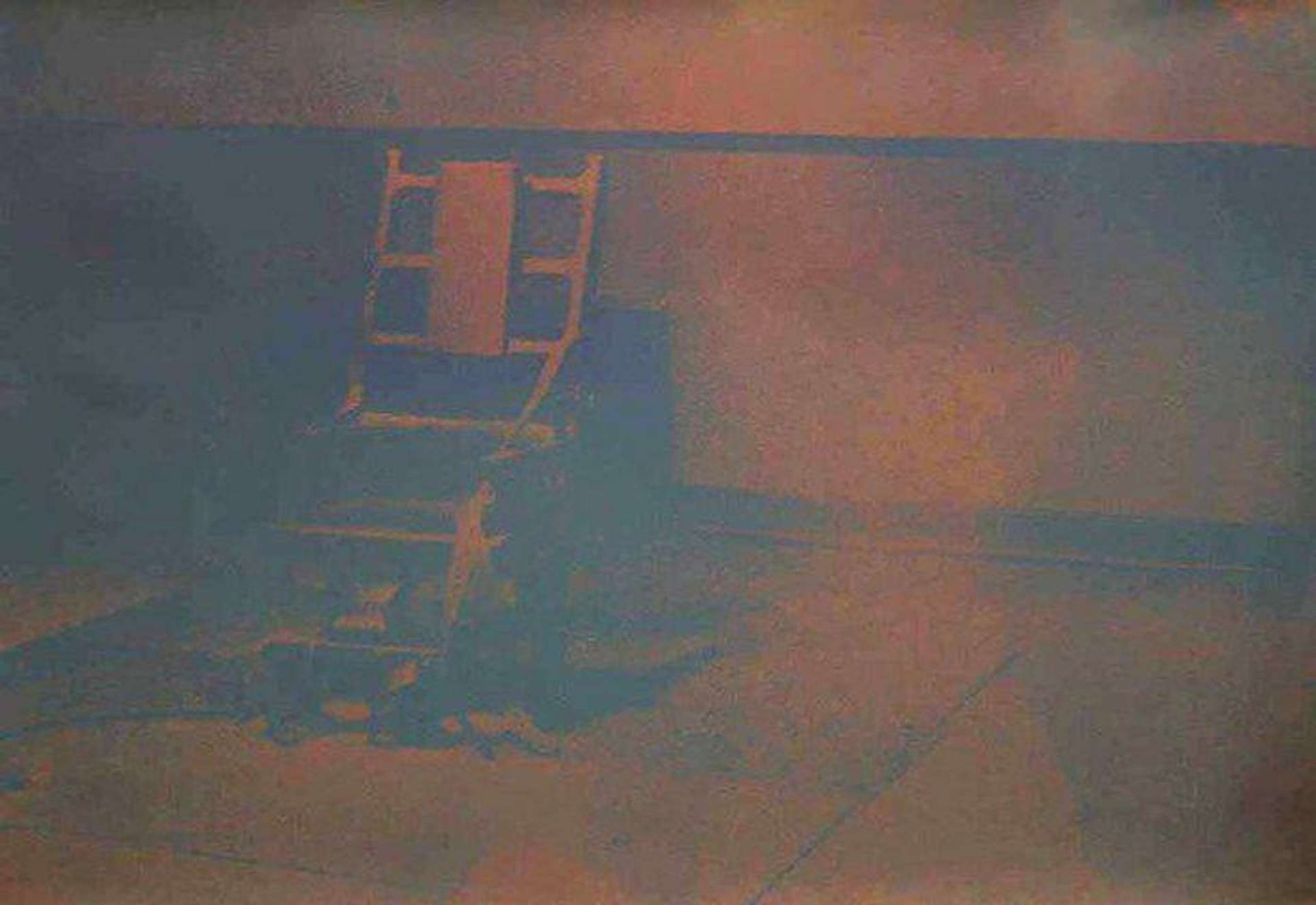

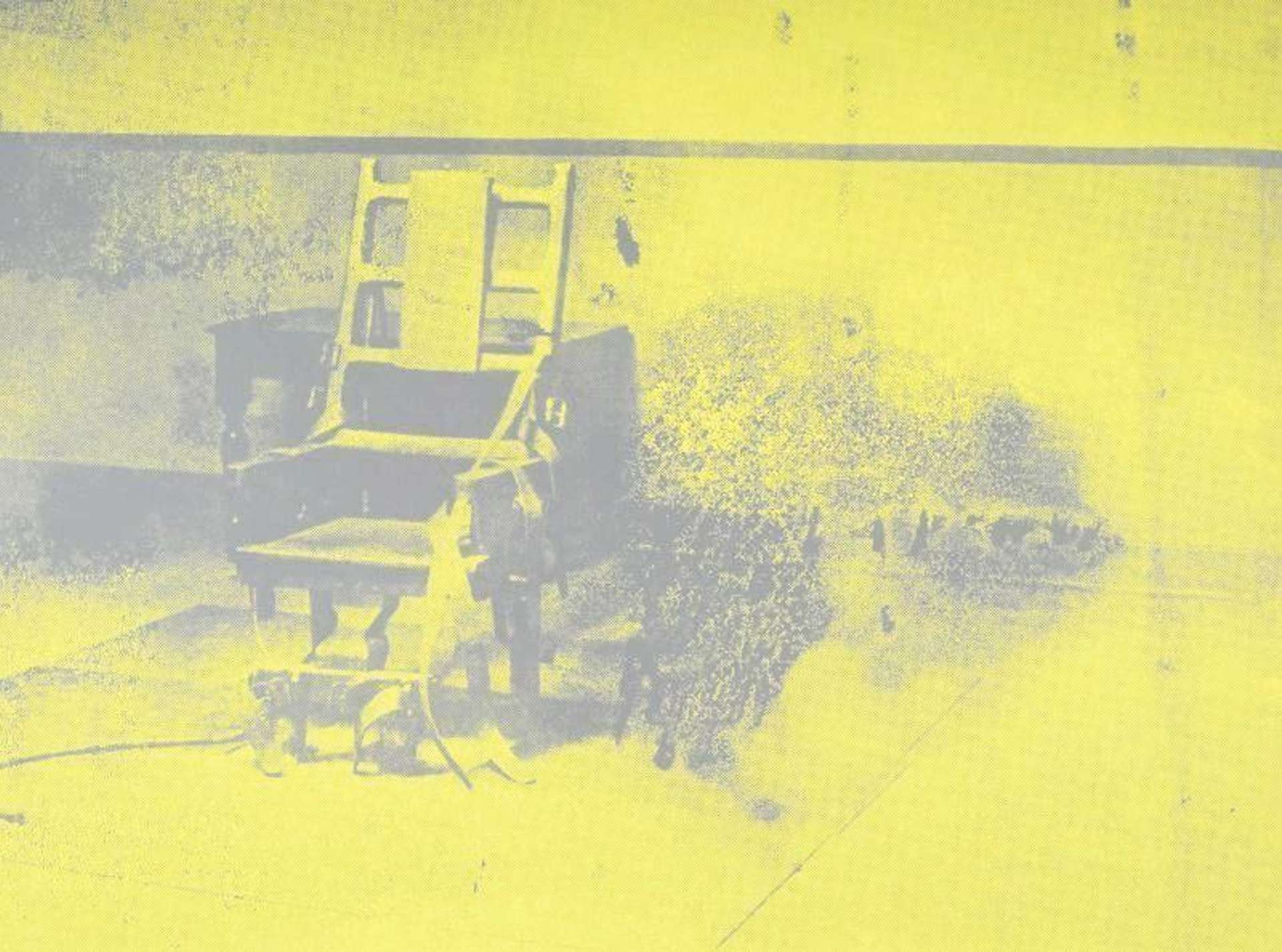

Electric Chair (F. & S. II.79) © Andy Warhol, 1971

Electric Chair (F. & S. II.79) © Andy Warhol, 1971MyPortfolio

Read Chapter Seven of Richard Polsky’s mini series on the world of Andy Warhol authentication.

Chapter 7

While Alice’s Warhol was being enjoyed by visitors to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I was contemplating what was next for the painting. The experience at Bonhams made me realise that I needed to go in another direction, possibly working with a regional auction house that saw the painting as an opportunity. There were literally a few thousand small auction houses scattered across America. Naturally, some were better than others — and some were more honest than others.

The real problem was the majority of them simply lacked the expertise to know the true identity of the artist they were taking on consignment. There is simply too much to learn to be an expert in every major painter. So, when a collector brought in a painting derived from comic book imagery, the auction house staff member would often label it as a Roy Lichtenstein. Maybe it was — but it probably wasn’t.

However, the top regional auction houses (and there were only a handful), went the extra mile to be as careful as possible, as far as the consignments they took on. Among them were Rago, L.A. Modern, and Hindman. I thought each of these companies had potential, as far as selling Alice’s painting. But the more I thought about it, I realised they’d probably come up against the same issue that haunted Bonhams — “Why wasn’t the painting being sold by Sotheby’s, Christie’s, or even Phillips?”

A few years passed, while I kept my eyes open for opportunities. Oddly enough, I thought about an interview with the basketball great Michael Jordan. When he came into the NBA as a rookie, he had a hard time adjusting to the rigours of playing professional basketball. Jordan was trying too hard and forcing the action. Then one day something clicked. He realised he needed to slow down and go with the flow. As he put it, “I let the game come to me.”

I realised this principle could be applied to everything in life; including the art business. One day, early in 2021, I was scanning my emails when I came across an announcement from Larsen Art Auction, in Scottsdale, Arizona. It featured a painting by the Native American artist Fritz Scholder. I took a closer look because I once owned a Scholder and was curious about his current market. That’s when it occurred to me that Alice Cooper also lived in Scottsdale. Since I already had visited the Larsen’s space, and had done some art authentication work for their company, I felt comfortable contacting them — to see if they might be interested in auctioning Alice’s painting.

Beginnings

We had a productive initial conversation. It turned out that Scott and Polly Larsen knew Alice and that he occasionally stopped by the gallery with his wife Sheryl. When I broached the subject of the painting, they immediately expressed their enthusiasm. I filled them in on its market history and the recent misfire at Bonhams. Scott Larsen wasn’t the least bit concerned; he was all in. As he put it, “We’d love to handle the painting — we know it’s 100% genuine.”

A call was placed to Shep Gordon, who responded, “I don’t know, Richard. I’ve never heard of Larsen. Maybe we’ll just hang onto the painting…”

Fortunately, I managed to convince Shep to keep an open mind to Larsen’s bona fides: they knew Alice and Sheryl, they had been in business for 25 years, and they had a spotless reputation. I also pointed out the goodwill we’d likely receive because of Alice’s hometown connection, the fact that Scottsdale is an affluent community with a lot of art buyers, and Larsen’s offer to donate part of the proceeds to Alice’s “Solid Rock” non-profit foundation.

Shep said, “Look, I have a good friend in Scottsdale named Danny Zelisko (a fellow rock promoter). Let me see if he knows them.”

Later that day, Shep called me back, “Danny vouched for the Larsens and said they’re good at what they do.” He paused, “Okay, let’s give it a shot.”

Not long after, we signed a contract to auction the painting. With Covid still a factor, rather than sell it in the spring, we decided to shoot for the fall when the chances of a live audience looked more realistic. A date was set; 23 October, 2021.

Consigning an Andy Warhol artwork to auction

Negotiations with Scott and Polly Larsen were smooth. We settled on a pre-sale estimate for the Little Electric Chair of US$2.5-3.5 million. Determining the right estimate, as the expression goes, is more of an art than a science. Too low of an estimate and you disrespect the object. Too high and you scare away potential bidders. You’re always looking for that sweet spot that encourages bidding. You want collectors to believe they have a realistic chance of succeeding. Our logic was that if the painting had been included in the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, it would have been estimated at US$5-7 million. Offering it at half that figure felt right.

Next, we had to settle on a reserve. A reserve is the minimum amount of money that the seller is willing to accept for his property. However, the reserve cannot exceed the low end of the estimate. In this case, since the low end was US$2.5 million, the reserve could not go above this figure. But it could be lower. In this case, I left it up to Shep to decide what he was comfortable with. The reserve was always kept confidential between the auction house and the consignor.

Once the estimate and reserve were agreed upon, Scott Larsen hired a local public relations firm to promote the painting. Trying to capitalise on Alice’s celebrity appeal, individual mailings were sent out to a list of key collectors in Hollywood. Besides art buyers, the public relations firm also pursued collectors of rock memorabilia. They even set up exhibitions for the canvas at a high-end auto show in Las Vegas and an elite Scottsdale jewellery salon. The Little Electric Chair also received plenty of exposure on television, with Alice showing up at the Larsen Gallery to give an interview — where he pretended to be shocked by the electric chair.

As the actual event drew closer, my wife and I booked our airline tickets and made reservations at a new hotel called the Canopy, which was within walking distance of the Larsen Gallery. In the meantime, the Warhol market seemed to plateau. It wasn’t that there was a lack of interest in his work. Quite the contrary. The issue was a lack of material. A lot of “journeyman” pictures were available, but few works of quality. The Little Electric Chairs were considered upper-end Warhols — not the peak of the pyramid (like the Campbell’s Soup Cans, Marilyns, Lizes, Elvises, and multi-image Disasters) — but significant.

About a month before the sale, I checked in with Scott Larsen to see how it was going.

“Hi Richard,” said the ever-enthusiastic Scott, “We’ve had a great response to the painting.”

“Really,” I said, probably betraying my sense of relief.

“We just signed up a major dealer who’s planning to bid and we also have a number of wealthy collectors who have expressed serious interest.”

“So, do you have more than one person signed up to bid at this point?”

“No,” said Scott. “But typically people don’t register until the week of the sale.”

“Wow, it sounds like all of the publicity that you’re generating is paying off.”

“I think it is,” said Scott. “I feel confident we’ll sell the painting — it’s just a question of for how much.”

I got off the phone feeling almost giddy. I loved Scott Larsen’s confidence. It sounded like the painting was going to sell. I spoke to Shep and he also sounded encouraged. I was already thinking about the publicity campaign I was going to run after the auction. Here was an opportunity to trumpet how my art authentication service led to a multi-million dollar sale of a classic 1960s Andy Warhol. I was sure that this would trigger a rush of business, to say nothing of the prestige associated with having a celebrity client.

Auction Day for the Little Electric Chair

About two weeks before the auction, Covid continued to spike and we wound up cancelling our trip. When I heard that Alice and Shep also weren’t attending, I felt a little better. I had been looking forward to hanging out with them and hopefully attending a celebratory dinner after the sale. Fortunately, the auction could be viewed live over the internet —so I could still watch the painting sell.

Finally, the great day rolled around. I got online early to make sure everything was working properly. I even spoke with a Larsen employee who told me they had 150 people alone watching it on Invaluable. As I scanned the sales catalogue, I noticed how the Little Electric Chair was positioned so it would come up mid-way through the auction — hoping to create some positive momentum. This was a typical auction house strategy. It was analogous to how you have an opening act at a rock concert to warm up the audience before the headliner. You always wanted your star lot to come up directly after a carefully chosen high-profile lot that you knew would sell.

The sale got underway and the tension mounted as I observed picture after picture find a buyer. The auction couldn’t go by fast enough. Most of the lots were low-ticket items in the US$1,000-$5,000 range. There were a few six-figure pieces scattered throughout the sale. But nothing came close to the million-dollar price tag on Alice’s painting.

At long last, I heard the auctioneer call out, “And now we come to the red Little Electric Chair.”

He then proceeded to go through the painting’s lengthy backstory. The tale was filled with hyperbole. But I suppose that was the point. I thought to myself, "If he doesn’t have any bidders lined up by now, his sales spiel isn’t going to help him."

The auctioneer opened the bidding at US$1.6 million. I watched him scan the audience anxiously looking for someone to raise his paddle. But the room went cold. He then made eye contact with several people who were manning the phones, hoping for a phone bidder. But there was no action on that front.

After refocusing his attention on those seated in the room, he finally gave up after about 15 seconds. Alice Cooper’s red Little Electric Chair, which came into his possession literally half-a-century ago, still belonged to him.

Disappointed hopes: Alice Cooper's painting fails to sell at auction

I quickly called Scott Larsen on his cell phone even though the sale was still in progress. I sensed the profound disappointment in his voice when he said, “We’ll try and sell it privately.”

Before he could utter another word, my phone buzzed; it was Shep.

“Get the painting back,” was all he said.

The sale’s aftermath was not pretty. Given all of the advance publicity the painting received, I knew the press “follow-up” would be fast in coming. Publication after publication gleefully announced that the painting failed to find a buyer. I received a fair share of calls from the media asking for a comment. In most cases, I simply stated the obvious: “The painting didn’t sell because no one bid on it.” Artnet, whose online publication I had frequently written for, also solicited a quote. I told them: "Alice Cooper's red Little Electric Chair is authentic. However, although Christie's set a precedent for selling Warhol paintings not included in the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, auction results can be unpredictable. I believe in the future Alice's painting will ultimately wind up in a significant collection."

A few days later, as the dust began to settle, Scott Larsen sent Shep and I an email alluding to having two potential private buyers interested in making offers. Technically, the sales contract gave Larsen Art Auction 60 days to sell the painting privately. When a painting passes at Sotheby’s and Christie’s, they often receive multiple inquiries after the sale from “bottom feeders” looking for a bargain. If the consignor is lucky, his property will attract several offers, leading to a mini-bidding war. Sometimes the painting winds up selling for within its original estimate. But alas, neither of Scott Larsen’s leads panned out.

Although I continued to check in periodically with Scott, nothing seemed to develop. In retrospect, it seemed like anyone with a few million dollars to invest in a Warhol wanted reassurance that the painting was liquid, if he decided to resell it in the future. The irony was that if Alice’s painting had sold at Larsen, it would have demonstrated the very liquidity a buyer would have been looking for.

Once the 60 day post-sale option had expired, the painting was returned to Shep Gordon, who promptly placed it in storage at Crozier in New York. In the ensuing months, I kept in touch with him but the conversations were brief. Our mutual frustration was based on the knowledge that we were sitting on a genuine Andy Warhol painting — and neither one of us could figure out the next step. About the only thing I could come up with was approaching a major gallery to see if I could interest them in hanging the painting — along with a small group of other Warhols I authenticated. It was common knowledge in the art world that there were a number of authentic Warhols not included in the catalogue raisonné. Perhaps an exhibition of some of them might shake things up. The trick, of course, was finding an important enough gallery to sponsor it. However, the Catch-22 was that the top galleries in the world weren’t interested in doing anything controversial. They didn’t need to.

Then, out of the blue, I heard from Shep, “Are you ready for this? I got a call from someone who wants to buy the painting and cut it up into tiny squares — and make NFTs out of them!” (If you can believe it, this company has already been doing this to Banksys, Rothkos, and more.)

I was stunned by the absurdity of the idea. I quickly said to him, “I’m certainly familiar with the current NFT craze. But I can’t imagine selling the painting to someone who wants to cut it up. This sounds like a really bad idea.”

“I agree,” laughed Shep.

And that was the last he heard from the caller.

Keep reading: 'I Authenticated Andy Warhol.'

Read the previous instalment of the series here.

Richard Polsky is the author of I Bought Andy Warhol and I Sold Andy Warhol (too soon). He currently runs Richard Polsky Art Authentication: www.RichardPolskyart.com