Brillo

Box

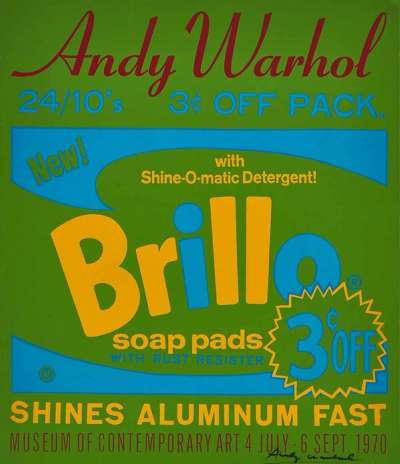

Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box prints follow his oversized wooden sculptures of the cleaning product’s packaging, displayed in New York, in 1964. They reveal Warhol’s obsession with the mass-produced products and marketing of consumerism— which also saw him create enlarged Kellogg’s boxes, and his celebrated Campbell’s Soup Can paintings.

Andy Warhol Brillo Box For sale

Brillo Box Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Brillo (Pasadena Art Gallery Poster) Andy Warhol Signed Print | 3 Sept 2025 | Lama | £1,870 | £2,200 | £3,000 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

A signed print nodding to one of Warhol’s most acclaimed sculptures, Brillo Box epitomises the principles of the burgeoning Pop Art movement. America witnessed major economic development in the post-war period. Concurrent with this was a boom in advertising and consumerism. It was in this context that Pop Art was born. Warhol found inspiration in the products that characterised everyday life; Coca-Cola bottles, Campbell’s Soup cans, dollar bills and Brillo soap pads. In a decisive break with the artistic traditions of the past, he elevated these banal objects, transforming them into high art. He was fascinated by their democratic power and the way in which they defined the American consumer experience, famously stating: “A coke is a coke and no amount of money can get you a better coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the cokes are the same and all the cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.” The artist was also interested in the visual power of brands and packaging as well as the serial means by which they were produced. In 1963, a year before he exhibited his first Brillo Box (3c off) sculptures, Warhol responded to the question ‘What is Pop Art?’ in an Art News interview: “The reason I'm painting this way is that I want to be a machine, and I feel that whatever I do and do machine-like is what I want to do.” Warhol sought to appropriate the visual language of mass production and apply it to his art.

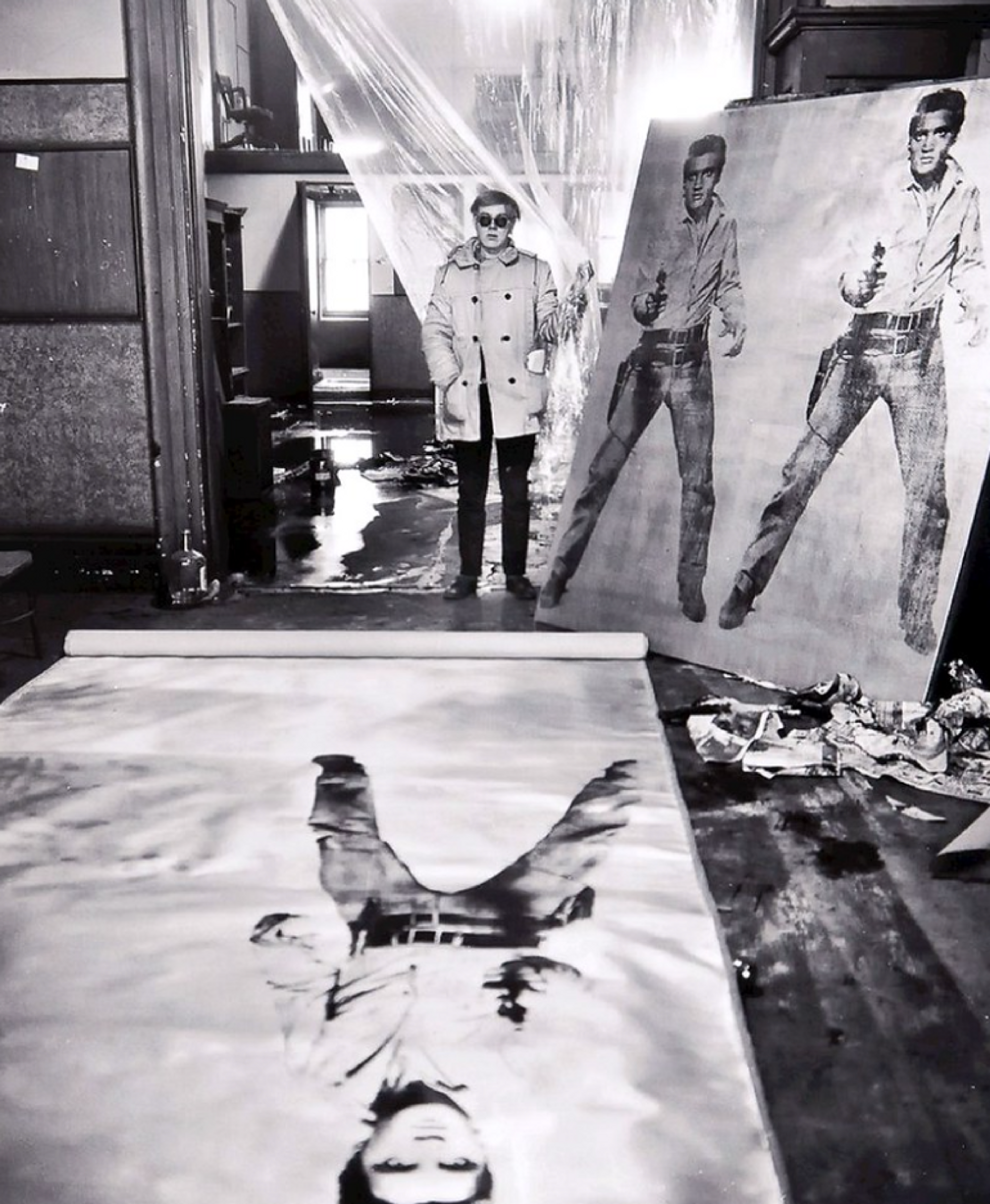

In 1964 the artist first exhibited a small number of yellow Brillo Box (3c off) sculptures in a group show called Boxes at the Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles. For his first sculpture exhibition at the Stable Gallery in New York a few months later, Warhol and his assistants Billy Name and Gerard Malanga received a truck load of fabricated wooden boxes into the studio, onto which they screen printed each box with exact replicas of brand logos such as Heinz, Del Monte and Brillo. The outcome was a gallery stacked high with several hundred wooden boxes that looked almost indistinguishable from supermarket cartons in a stockroom.

The series mimicked a commercial process of production and resulted in sculptures directly inspired by everyday consumer brands. The Brillo Box and Brillo Box (3c off) works exhibited in the 1964 Stable Gallery exhibition were archetypal of Warhol’s embrace of everything previously considered non-art; the materials and images of everyday popular culture; magazines, comic books, news media, film stars, advertising and products. The sculptures presented a decisive break with the artistic conventions of the past, particularly those of the Abstract Expressionists. The Brillo Box sculptures were a clear statement that resisted expressionism and the individual hand of the artist, traditionally indicators of originality, and instead espoused machine-like graphic precision and objectivity.

Warhol’s Brillo Boxes were controversial and shocking at the time they were unveiled. The sculptures remain fresh and contemporary almost sixty years after their production and attest to writer and cultural critic Gary Indiana’s statement: “Warhol rewired your perception of what you already knew.” Their celebration of newness, the everyday, and American popular culture has led the Brillo Box series to become one of Warhol’s most notorious and acclaimed bodies of work.