A Closer Look at Banksy’s Soldiers and Militants

Applause © Banksy 2006

Applause © Banksy 2006

Banksy

269 works

Banksy has for years transformed the plain walls of urban landscapes into poignant commentaries on contemporary society, accessible for all to see. His stencil-driven pieces, sometimes whimsical yet always provocative, push the boundaries of street art and challenge viewers to question the world around them.

Among his most compelling subjects are his depictions of soldiers and militants. These are not just any renditions of war and conflict, but are poignantly timed and deeply imbued with Banksy’s characteristic mistrust of authority and anti-war activism. Drawing from his overarching theme of rebellion and scepticism towards traditional power structures, his soldiers and militants serve as metaphoric mirror reflections of society. By examining specific instances of militaristic and militant representation, viewers are able to engage with various issues relevant to our times.

Happy Choppers

First created and stencilled in London in 2002, Happy Choppers features a squadron of military attack helicopters with a twist – one of the helicopters has a large pink bow atop its cockpit. The juxtaposition of the menacing war helicopters with an innocuous, playful element like a pink bow is classic Banksy: it captures a blend of humour and critique, making the viewer question the nature of war, aggression and societal acceptance of these values. The motif was eventually released in two silkscreened print editions in 2003.

In the broader context of Banksy’s work on soldiers and militants, Happy Choppers underscores the absurdity and contradictions inherent in militarism. By introducing an element of childlike innocence to a symbol of warfare, Banksy challenges viewers to reflect on the ways in which society normalises and even romanticises violence. We often think of war as a necessary means to the ultimate end, pacifism, but is that really true?

Like much of Banksy's art, Happy Choppers goes beyond just a visual statement; it is a call to think deeper, to question authority and to not take things at face value -- especially things said to us by those in power.

Love Is In The Air (Flower Thrower)

Love Is In The Air, commonly referred to as the Flower Thrower, stands as one of Banksy's most emblematic creations, encapsulating a vivid juxtaposition of peaceful resistance against a backdrop of violence. It depicts a man, poised in an aggressive stance and dressed in rioter’s gear – yet the artwork deviates from the expected narrative by having the man throw a bunch of flowers instead of a molotov cocktail or stone. This potent contrast presents a compelling commentary on the transformative power of peace and love over violence and the potential of beauty as an antidote to oppression.

First making its mark on a wall in Jerusalem's West Bank in 2003, the mural became Banksy's poignant statement on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Positioned in a region historically steeped in conflict, its vibrant message of peace amidst turmoil resonated deeply. Yet, the universality of its theme ensured its relevance was not confined to this specific geopolitical issue. The image was eventually released as a print later that same year. Across the world, audiences have found a reflection of their own aspirations for peace and harmonious coexistence in the Flower Thrower.

Over the ensuing years, this iconic image has been widely reimagined and reproduced, by Banksy himself and others. Evolving into a global symbol of hope and peaceful protest, its enduring appeal lies in its urging of viewers to reflect on their own responses to conflict and to consider the transformative potential of love and understanding.

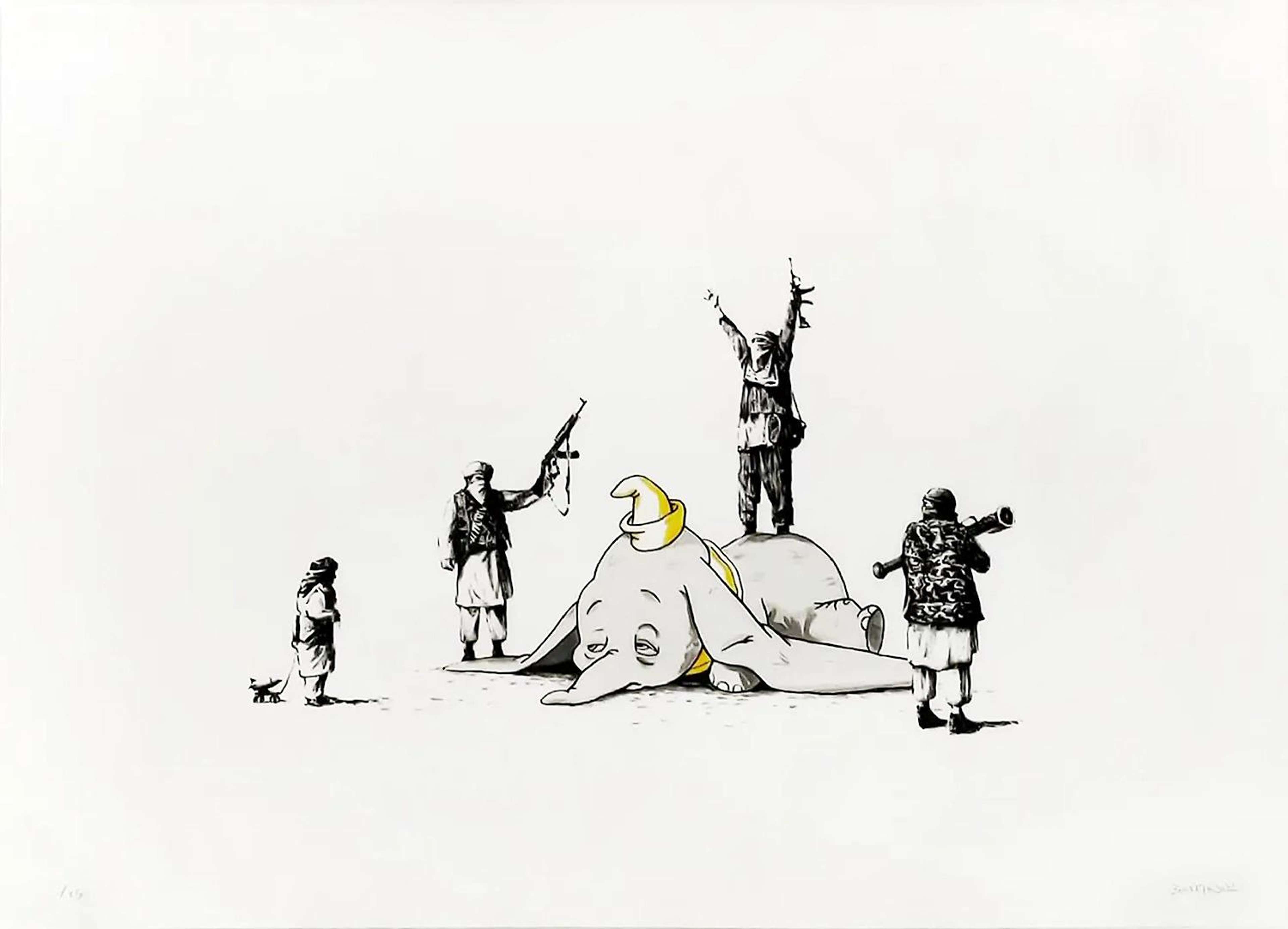

Dumbo

Dumbo, from 2014, is a physical representation of the final frames of his film Rebel Rocket Attack, which was unveiled by Banksy during his 2013 New York residency. The arresting visual presents rebel militants triumphantly perched atop a grounded and frazzled Dumbo, their weapons proudly brandished skywards. With Dumbo's stark black and white portrayal punctuated only by the vivid hue of his corn-yellow hat, the artwork demands attention. At its core, the artwork and its accompanying film are clearly not about a cartoon elephant caught amidst chaos. Rebel Rocket Attack initially seems to document Islamic militants shooting down the iconic Disney character. Its 2013 context is important, as a time where much of the Syrian conflict was being broadcast in gruesome videos widely available online. In true Banksy style, the video ends on a cheeky note: a child disapprovingly intervenes towards the end, a symbol of hope and rebellion amidst the violence.

A jarring mix of the familiar and the surreal, the video – like all of Banksy's works – has more than meets the eye. Dumbo, the embodiment of Disney and by extension, American cultural influence, possibly mirrors the American military presence in the Middle East. Additionally, the film was a stark reminder of the age of misinformation, where propaganda can be seamlessly masked as truth.

Banksy's Dumbo, both in print and as a motion picture, navigates a multitude of sensitive terrains. It's a reflection on Western intervention, the malleability of “truth” in the digital age and the power of media in shaping perceptions. The fallen elephant, surrounded by rejoicing militants, encapsulates a disturbing reality, urging viewers to consciously engage with the material they consume, questioning the narratives they are presented with.

Rebel Rocket Attack (2013), a video by Banksy.Flag

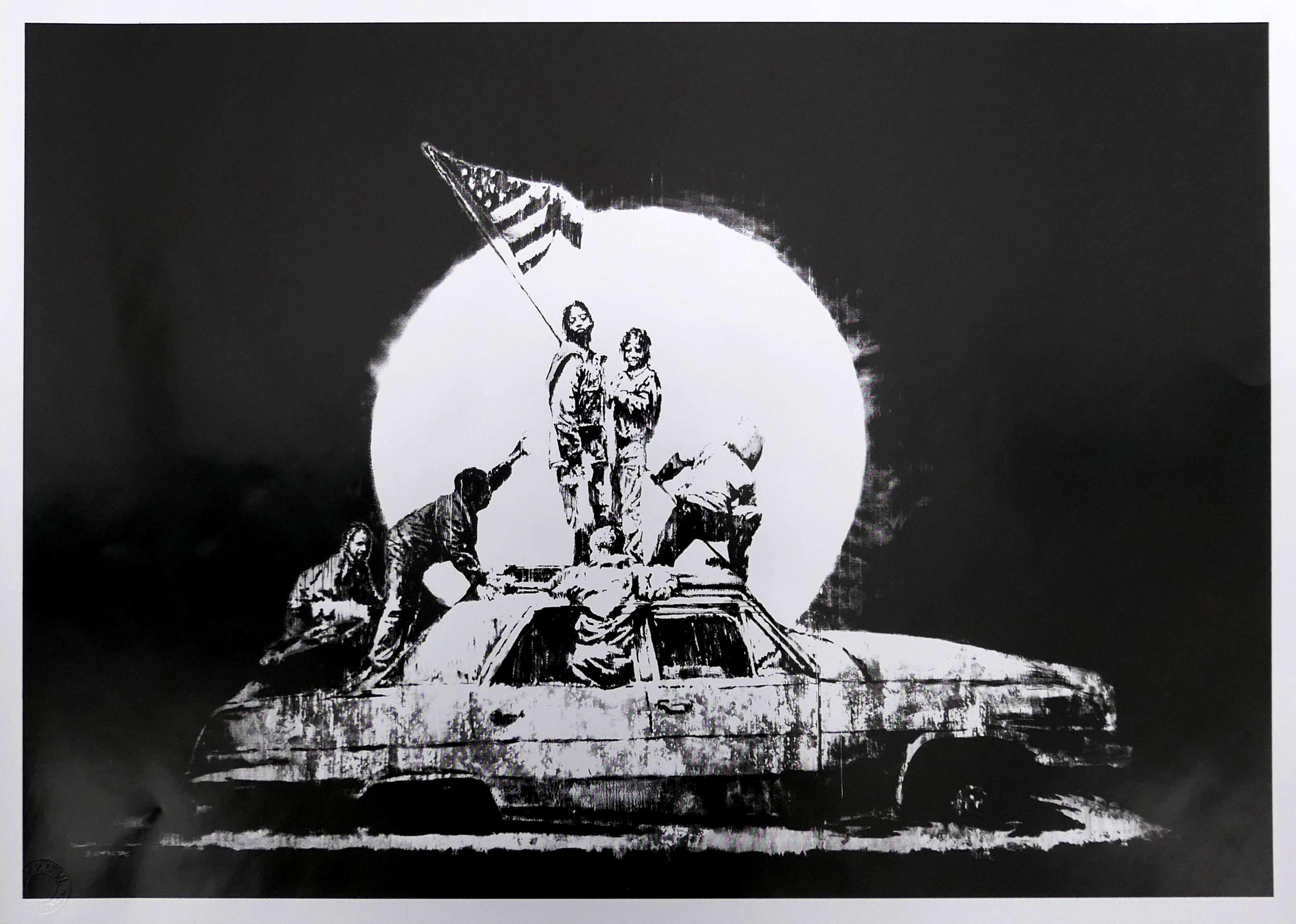

Banksy's subversive style is clearly seen in Flag, from 2006. The monochrome screen print showcases Banksy's unparalleled ability to intertwine humour, critique and deep societal commentary. The prints were originally released as part of Banksy's 2006 Santa’s Ghetto exhibition in London, and came in silver and gold. The silver edition is especially popular, particularly the rare ones printed on formica with Banksy's signature etched in – of which only 20 exist.

At first glance, Flag pays homage to Joe Rosenthal's iconic Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, which captured six US Marines hoisting the American flag atop Mount Suribachi during World War II. However, in classic Banksy style, a closer look reveals a stark departure: instead of soldiers, urban youths scramble atop a car while two female figures anchor an American flag, set against the luminescent backdrop of a large silver moon. This calculated subversion moves from a tribute to a critique – probing not only American militaristic endeavour overseas but also drawing attention to the disenfranchisement of Western youth at home.

The powerful imagery of Flag, rife with contrasts, elicits a plethora of interpretations. Yet, one cannot help but ponder on the American Dream and its juxtaposition of promise against its worldwide legacy of violence and unrest. By replacing marines with figures of disenfranchised youth, Banksy's work highlights the ironies embedded in Western imperialism and forces viewers to reflect on the foreign and domestic implications of such a policy. In doing so, Flag cements itself as a poignant reflection on the nuances of power, legacy and societal aspiration.

Golf Sale

Banksy further presented a powerful visual discourse in his 2003 screen-print Golf Sale. At the core of this artwork lies a masterful intertwining of iconic imagery, consumerism and an artistic twist on the audacity of human spirit.

Drawing directly from one of the 20th century's most potent moments of individual defiance, Golf Sale mirrors the unforgettable 'Tank Man' of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. This lone figure, immortalised in photographs, stood in peaceful protest against an advancing row of Chinese military tanks. Through this symbolic act, he became an emblem of resistance against oppressive regimes and a representation of the power of one amidst the many.

Yet Banksy's adaptation introduces an unexpected twist, embedding a satirical undercurrent into this tableau of resistance. The solitary protester's placard, instead of bearing a politically charged message, simply reads "GOLF SALE", directing passersby to an ongoing sale. Herein lies Banksy's genius: by juxtaposing the gravitas of Tiananmen Square's historical moment with the mundane capitalist allure of a golf sale, he underscores the absurdities of modern consumerism. Through this lens, Golf Sale raises questions about societal priorities and the frequent overshadowing of significant historical or political events by fleeting consumerist distractions.

As with many of Banksy's creations, Golf Sale serves multiple roles: it is at once a tribute to the defiant spirit of activists worldwide and a scathing critique of capitalism's relentless grip on contemporary society.

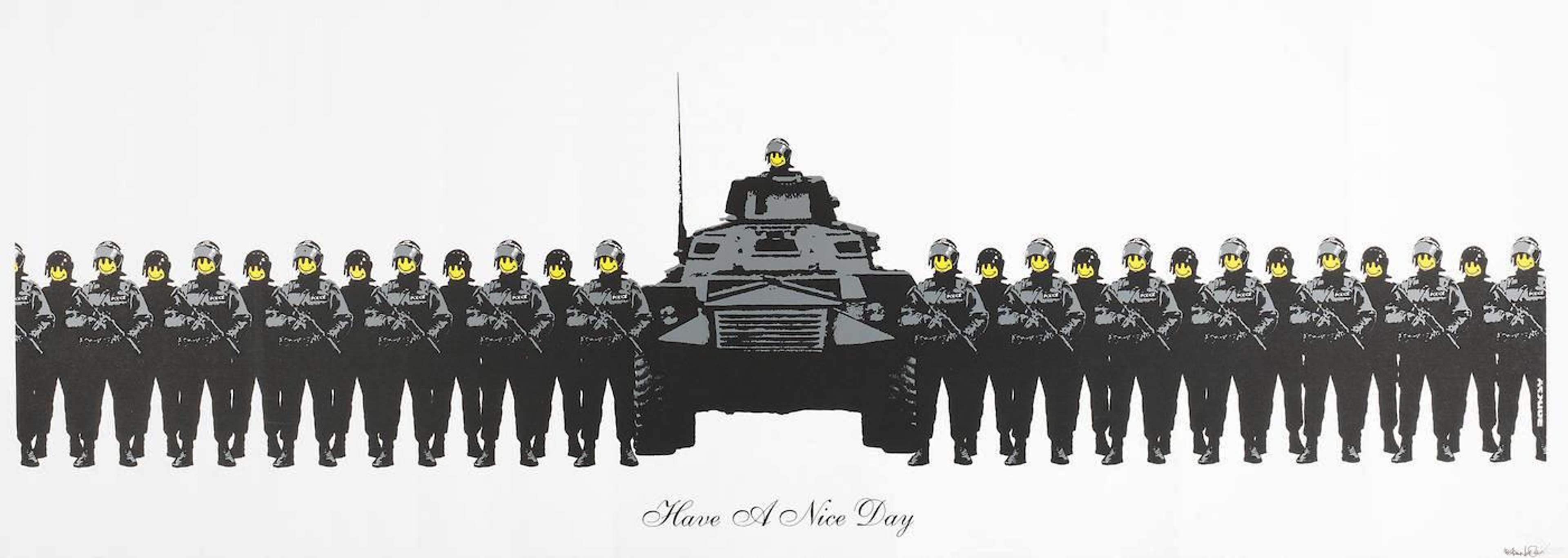

Have A Nice Day

Banksy deftly delves into the heart of authority and its inherent contradictions in his screen print Have A Nice Day. Done in an unusual landscape form, the composition is dominated by a formidable array of military or riot police, with a looming tank strategically centred amidst them. The piece's title is written underneath the group and drips with irony, standing in stark contrast to the intimidating brigade. This immediately compels viewers to reflect on the dissonance between the message and its visual representation, but it's the acid-house smiley face pasted over each officer's visage, that truly amplifies the work's subversive quality. The smiley, a symbol historically synonymous with joy and positivity from its pop culture inception in the 1960s, undergoes a potent transformation under Banksy's hand.

By superimposing this emblem onto faces of authority, Banksy not only obscures the identity of the enforcers but also fundamentally alters the viewer's perception of them. The once comforting smiley, now juxtaposed against a militaristic backdrop, takes on darker undertones. Banksy's choice is no random act; the smiley face, over the decades, has been reclaimed and repurposed by varied movements, from horror genres to political extremists, exemplifying its malleability as a symbol.

In Have A Nice Day, Banksy masterfully interweaves this cultural evolution of the smiley and situates it within the larger discourse on the facades of authority. The print forces its audience to grapple with the duality of symbols, the oftentimes deceiving nature of power, and the unsettling reality that beneath an affable exterior may lurk a more sinister reality.

Precision Bombing

Banksy, with his knack for capturing societal anxieties through visceral visuals, unveils a world of surveillance, vulnerability and the omnipresence of unseen powers in Precision Bombing, created in 2000. This artwork serves as a poignant commentary on government overreach and the omnipotent eye that seemingly hovers over our every move.

The scene depicts five stencilled figures converging on a vehicle. Yet, looming overhead is the unmistakable mark of a precision pointer, signalling imminent danger and turning this potentially covert assembly into a narrative infused with tension and imminent doom. This target symbol, central to the piece, becomes a metaphor for Banksy's broader themes of paranoia and surveillance. As seen in various other works by the artist, there is a consistent undercurrent suggesting that in the modern world, privacy is an illusion and that the populace remains perennially under the watchful eye of an elite few.

Moreover, Precision Bombing encapsulates a critical transition point in Banksy's artistic trajectory. Showcased for the first time at Severnshed, a venue in his native Bristol, the piece heralded his shift from freehand techniques to the more tactical and efficient use of stencils. This transition was not just a stylistic choice but also a strategic one: the swiftness of stencil artistry significantly reduced the time spent on location, a valuable asset for a street artist looking to evade the ever-present threat of police intervention.

Beyond its immediate imagery, Precision Bombing encapsulates the zeitgeist of our time — an era increasingly marked by heightened scrutiny, the erosion of personal liberties and the omnipresent shadow of conflict. It also stands as a testament to Banksy's evolving techniques and his ability to continually adapt, all while still delivering his unmistakably biting societal critiques.

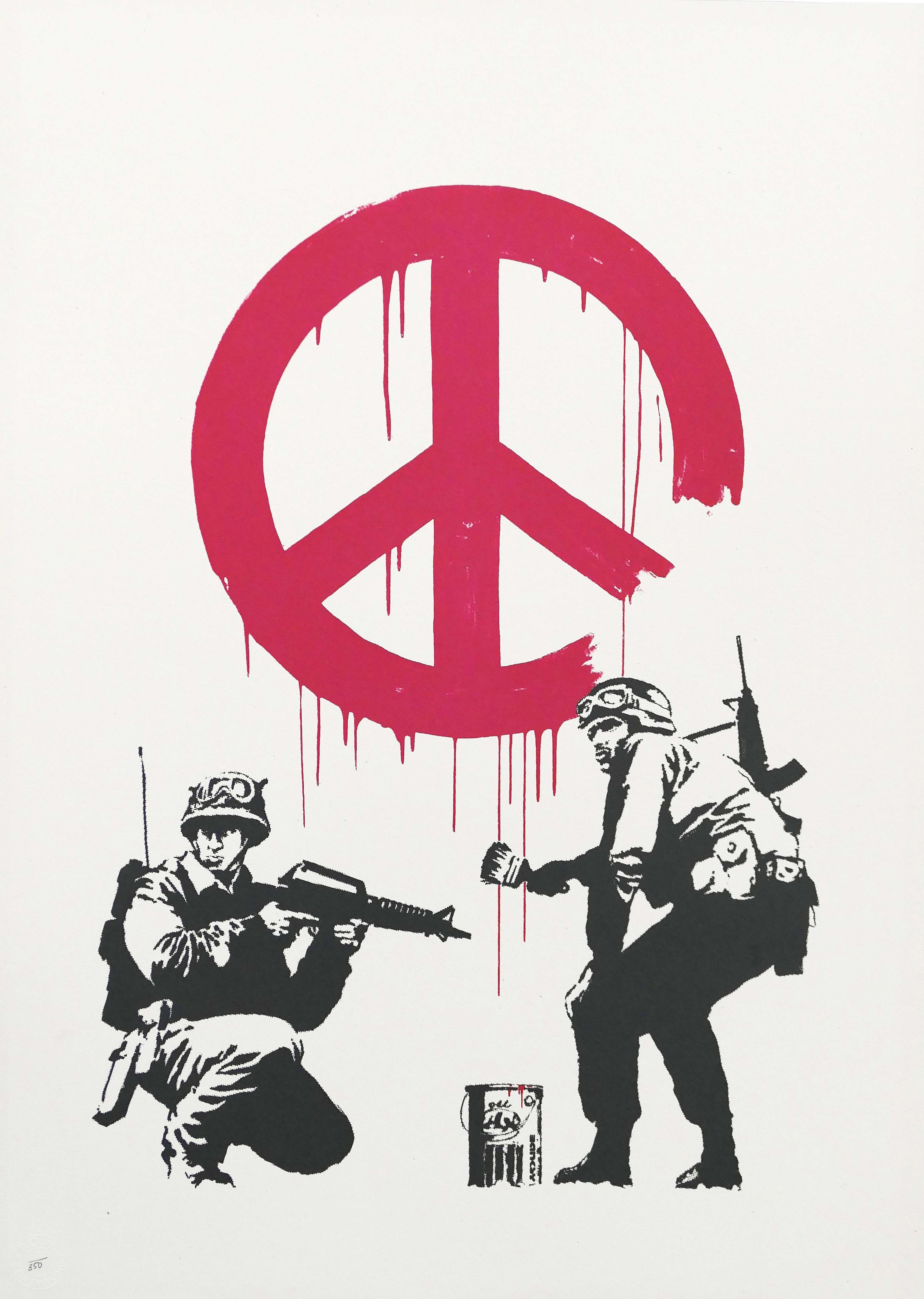

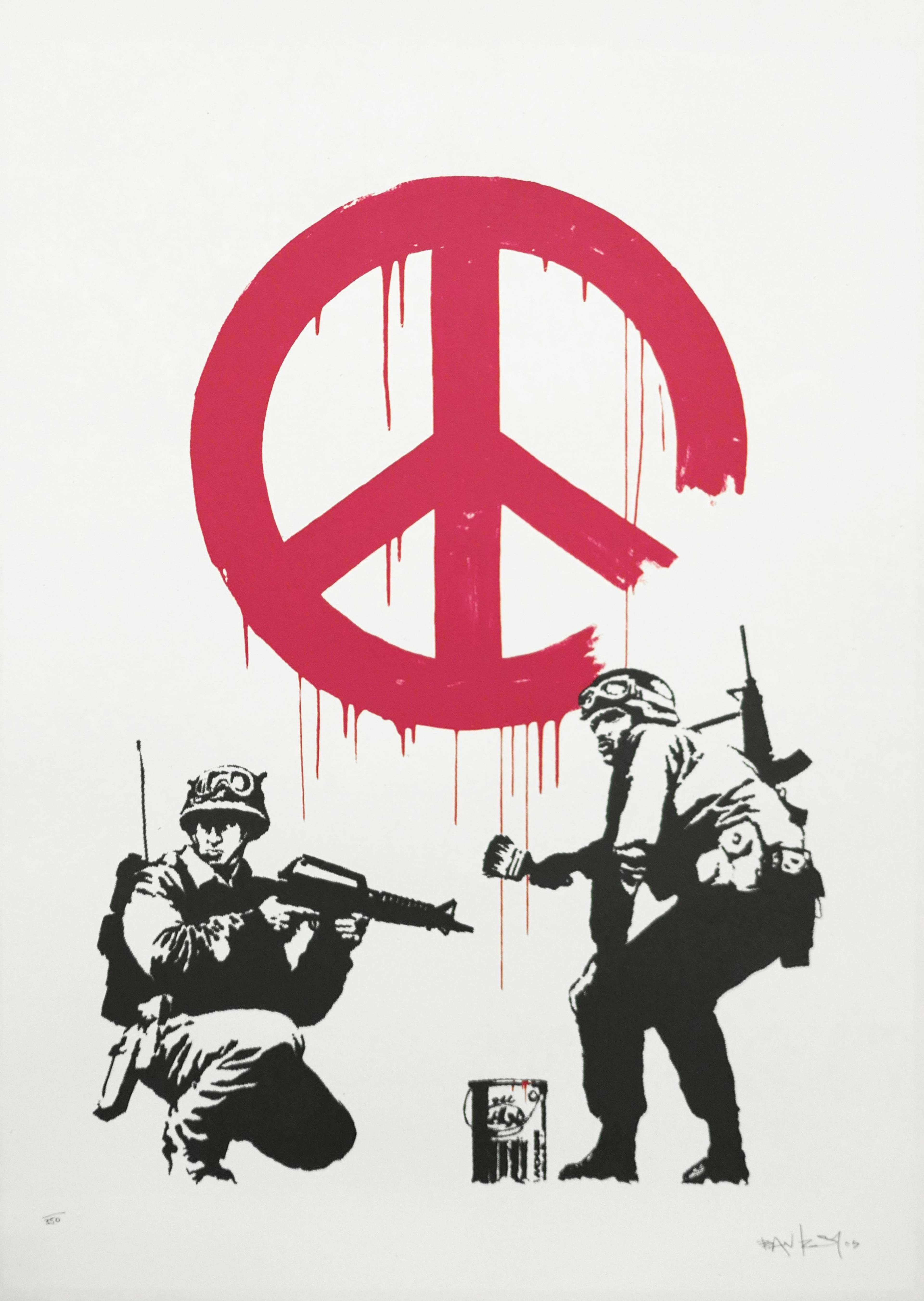

CND Soldiers

Banksy once again pushed the boundaries with CND Soldiers, an image that began as mural painted tantalisingly close to the Houses of Parliament in London and was later adapted into a screen-print edition in 2005. Rendered in the aftermath of the UK's divisive involvement in the 2003 Iraq war, it is not just another piece on a wall – it captures a nation's sentiments and resistance against the controversial decisions of its leadership.

CND Soldiers features two soldiers, meticulously stencil-sprayed, caught in an arresting tableau: bearing the familiar trappings of warfare with machine guns, one keeps guard while the other holds a paintbrush, crafting a vibrant red peace sign. This juxtaposition of the symbols of war and peace encapsulates a powerful message: even those within the system, the very soldiers ordered to wage war, long for peace. The use of monochrome for the soldiers – in contrast with a splash of primary colour for the peace symbol – further calls attention to peace as the main motif of the work, solidifying its place within the broader anti-war art movement.

The work is a poignant reminder of the masses who took to the streets in protest against the invasion of Iraq, including the very soldiers dispatched to fight. With this piece, Banksy illustrates the contrasting narratives of authority versus the ordinary citizen, while emphasising that the human desire for peace transcends duty and ranks.

Banksy vs. The System: The Activist Artist

In the world of contemporary art, Banksy is a force to be reckoned with. The celebrated artist continually pulls back the curtain on the ironies and contradictions of the modern age, using his rebellious art form to shape and respond to relevant issues. War and peace are recurring motifs in his work, and so is the place of human beings within these wider systems of power and oppression.

By encouraging his viewers to openly engage with anti-war art and ideology, Banksy further positions himself as a uniquely powerful voice in the world of activist art.