What Is Deaccessioning?

Image © Christie's / Portrait of George Washington © Gilbert Stuart 1795

Image © Christie's / Portrait of George Washington © Gilbert Stuart 1795Live TradingFloor

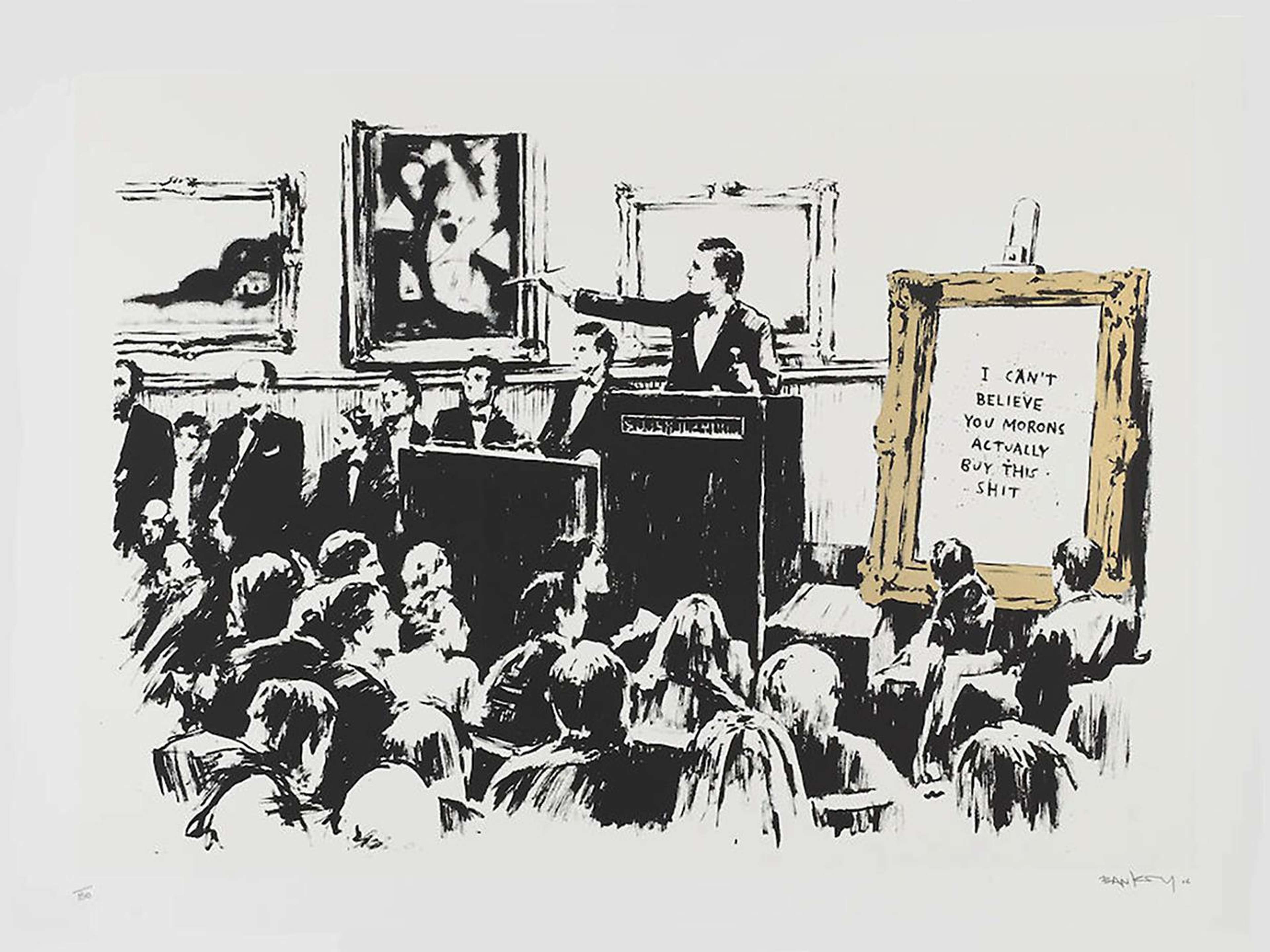

Controversy was raised in December 2023 when it was announced that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had deaccessioned its portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart and put it up for sale at Christies. The rare portrait, estimated to fetch between £1.2-2 million, was one of the artist’s earliest and will be sold to raise money for the museum’s acquisition fund. This is only the latest work the Met has deaccessioned, however, in alignment with its policy. From renowned art institutions to local history museums, deaccessioning plays a pivotal role in shaping collections that are meaningful and sustainable.

Understanding Deaccessioning: Definition and Process

Understanding deaccessioning in museums involves comprehending the careful process by which these institutions remove items from their collections. Deaccessioning is not simply about disposing of assets; it is a nuanced decision influenced by factors like an item's relevance, condition and its fit within the museum's mission and goals. The process starts with the assessment and identification of items that may no longer align with the museum's collection policy, considering aspects such as redundancy, condition issues, lack of relevance, or space constraints.

Once potential items for deaccessioning are identified, they undergo a thorough review by curatorial staff, often involving a collections committee or governing board. This critically assesses the historical, cultural, and monetary value of each item, its significance to the collection, and any potential legal or ethical concerns associated with its removal. This stage is crucial as museums must adhere to a framework of legal and ethical guidelines. These often stipulate that proceeds from deaccessioned items be used for collection-centric purposes, such as acquiring new items or conservation, rather than for operational expenses. The decision to deaccession an item demands a high level of transparency and accountability. If an item is approved for deaccessioning, its disposal can be managed in several ways, including sale, exchange, donation, or, in rare cases, destruction. Sales are typically conducted in a public manner, through auctions or direct sales to other institutions, fostering transparency. Throughout the deaccessioning process, meticulous records are maintained, documenting every step from the decision-making to the disposition of the item and the utilisation of any generated funds.

Historical Perspective of Deaccessioning in Museums

Deaccessioning is not a new concept. Museums have been refining their collections since their inception, although the reasons and methods have varied greatly over time. In the early days of museum development, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the focus was often on acquiring as many items as possible to create comprehensive collections. However, as collections grew, space and management considerations necessitated a more selective approach. During the mid-20th century, deaccessioning became a more formalised process. Museums began to recognise the need for clearer policies and procedures to manage their collections responsibly, a shift that was partly driven by the professionalisation of museum practices and the emergence of standards and ethics in the field.

Throughout time, several high-profile deaccessioning cases have sparked public and professional debate. These often highlighted the tension between the need for museums to adapt and refine their collections and the perception of museums as guardians of cultural heritage. Controversies typically arose from concerns over the loss of culturally significant items, the transparency of the deaccessioning process, or the use of proceeds from sold objects. For example, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, some museums faced criticism for deaccessioning artworks to cover operational costs, a practice generally frowned upon in the museum community. These incidents led to a reevaluation of ethical guidelines and policies governing deaccessioning. In response to these challenges, professional organisations like the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) and the International Council of Museums (ICOM) have established guidelines to help museums navigate the ethical and legal complexities of deaccessioning. These guidelines emphasise transparency, public interest, and the reinvestment of proceeds into the museum’s collection. They also discourage the use of deaccessioning funds for operational expenses.

Today, deaccessioning is recognised as a necessary, albeit complex, aspect of museum collection management. Modern deaccessioning practices are characterised by a focus on ethical processes, transparency, and the strategic refinement of collections to reflect the evolving missions of museums and changing societal values. As museums continue to grapple with challenges such as space limitations, changing public interests, and financial pressures, deaccessioning remains a vital tool for ensuring their collections remain relevant, dynamic, and sustainable.

The Ethical Debate: Pros and Cons of Deaccessioning

The ethical debate over deaccessioning in museums is a nuanced and multifaceted discussion, balancing the advantages and disadvantages of this practice. While deaccessioning offers significant benefits, such as enabling museums to keep their collections relevant and manageable by removing items that no longer align with their mission or are redundant. This process is not only about making space, but also about enhancing the quality and coherence of the collection. Additionally, deaccessioning can be a practical solution for conservation resource allocation, allowing museums to focus their efforts and funds on the most significant pieces. Financially, the sale of deaccessioned items can provide much-needed funds for acquiring new works or supporting existing collections, a benefit that is particularly crucial for institutions facing budgetary constraints. In recent years, museums have increasingly sold works by white male artists in order to fund the acquisition of works by artists of colour and women, addressing an important gap in their collections.

However, the practice of deaccessioning is not without its drawbacks. A primary concern is the potential erosion of public trust. The process, if not conducted with utmost transparency, can be perceived as a betrayal of the museum’s role as a guardian of cultural heritage. There is also the risk of losing valuable cultural heritage, especially if deaccessioned items are sold into private collections or leave the public domain. Another significant consideration is the impact on the art market; introducing major works can disrupt market dynamics, affecting both values and accessibility.

The ethical considerations in deaccessioning extend to the terms of item acquisition (particularly for donated items), legal restrictions, and the potential impact on donor relations. Professional guidelines advocate for a process that is transparent, well-documented, and ethically sound, emphasising that proceeds from deaccessioning should support the collection and not be diverted to operational costs.

Legal Framework and Policies Governing Deaccessioning

The legal framework and policies governing deaccessioning are critical components that ensure the practice is conducted responsibly. These frameworks vary by country and institution but generally include a combination of legal requirements, professional guidelines, and internal policies.

Legal constraints on deaccessioning often depend on the country's laws and the specific legal status of the museum. In Britain, for example, the British Museum Act of 1963 only allows works to be deaccessioned from the collection if they are duplicates of other works or are damaged beyond repair. Around the world, for publicly funded museums, there are usually stricter regulations which often require transparency and public accountability. These laws can dictate how proceeds from deaccessioned items are used, often mandating that they be reinvested in the museum's collection or other public-serving purposes. In contrast, private museums may have more flexibility but still operate under general laws governing property, contracts, and charitable donations.

Professional organisations play a significant role in shaping deaccessioning practices. Bodies like the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) in the United States and the International Council of Museums (ICOM) provide guidelines and standards. These emphasise the importance of ensuring that deaccessioning decisions are made in the best interest of the public, the museum's mission, and the integrity of the collection. They typically advise against using deaccessioning proceeds for operational costs, which can create a detrimental cycle where financial needs overshadow curatorial integrity, and stress the importance of transparency and due process.

Individual museums often have their internal policies regarding deaccessioning, which usually outline the specific criteria and procedures for considering and executing deaccessioning. They may include stipulations on how to handle potential conflicts of interest, the process for determining the value and best method for disposing of items, and guidelines for the use of proceeds. Institutional policies are often informed by both legal requirements and professional guidelines but can vary significantly from one museum to another.

Case Studies: Notable Examples of Deaccessioning

George Washington's portrait is not the first time the Met has deaccessioned works. In 1967, they were the subject of one of the first deaccessioning controversies, after selling several works from the estate of Adelaide Milton de Groot, who had donated them to the institution. One of these was Vincent van Gogh’s Olive Pickers. In 1989, the MoMA sold a Pablo Picasso work, in order to fund the acquisition of another van Gogh. In 2018, the Berkshire Museum was the subject of sanctions for controversially using the proceeds from the sale of deaccessioned works to fund an expansion of the institution; these sections included a temporary ban of loans or collaborations with other museums.

More recently, in 2021 the Met sold the same to 219 prints and photographs, including Roy Lichtenstein’s Brushstroke, in order to raise funds after the pandemic closures. It marked an exceptional occasion, during a two-year period where the Association of Art Museum Directors loosened its guidelines on deaccession and allowed museums to utilise funds from the sale of these objects to survive the economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. As a result, during the fall and winter of 2020, over £80 million worth of artworks were auctioned, including the Baltimore Museum’s Last Supper by Andy Warhol. Works by Jackson Pollock, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Gustave Corbet, Henri Matisse and Picasso were also auctioned by various American museums during that time. In April 2023, the Whitney Museum announced the deaccessioning and sale of an Edward Hopper painting, marking the first time it had sold a work since 2018. In December 2023, a plan by the Ministry of Justice to digitise and destroy millions of wills dating back to 1800 stoked significant controversy, in an extreme example of deaccessioning.

Impact of Deaccessioning on the Art Market and Collectors

Deaccessioning from museums significantly influences the art market and collectors, with a range of implications. When a museum opts to remove a piece from its collection, it can notably shift market dynamics, especially with high-profile works, which can alter the supply and demand balance and potentially impact the values of similar artworks or those by the same artist. Artworks with a museum provenance often carry additional value, and this history with a prestigious institution can heighten interest and drive up prices – making these pieces particularly attractive in the market.

For collectors, deaccessioning presents unique opportunities. It allows access to rare or unique works that were previously off the market, appealing especially to those with specific art interests or focus. From an investment perspective, museum deaccessioned artworks are usually seen as especially valuable, since they carry an implicit endorsement of their cultural and financial worth. Additionally, as museums adapt and refine their collections, it prompts collectors to reconsider their own, aligning with or contrasting the evolving narratives of major public collections.

The Balancing Act of Deaccessioning in Museums

Deaccessioning represents a critical and multifaceted aspect of museum management, balancing the needs of maintaining relevant and dynamic collections with ethical, legal, and public responsibilities. While it offers practical solutions for collection refinement, space management, and financial sustainability, deaccessioning also brings to the forefront complex ethical debates and impacts on the art market and collectors. This practice underscores the evolving nature of museums in responding to changing societal values and the continuous reevaluation of their role as custodians of cultural heritage.

The historical perspective of deaccessioning reveals its evolving nature, while the ongoing debates highlight the need for transparency and ethical integrity. Ultimately, deaccessioning reflects the dynamic interplay between preserving the past and embracing the future, reminding us of the ever-changing landscape of art and culture. As museums continue to navigate this complex terrain, their actions will undoubtedly continue to shape not only their own collections but also the broader understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage in society.