Free For All: The Origins and Importance of Public Art

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / Girl With Balloon © Banksy

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / Girl With Balloon © BanksyLive TradingFloor

Public art stands as a vibrant mechanism in facilitating the democratisation of culture, a means through which artists can shape and hear the voices and perspectives of communities in the public sphere. It serves as an egalitarian bridge, transcending the confines of galleries and museums to bring art directly to the people. From the towering sculptures adorning city squares to the intricate murals gracing urban facades, public art paints a vivid portrait of collective creativity and shared experiences. It embodies a profound spirit of inclusivity, inviting everyone – regardless of background or privilege – to partake in the transformative power of art.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / LOVE © Robert Indiana

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / LOVE © Robert Indiana What is Public Art?

Public art is a dynamic and diverse form of artistic expression intentionally designed for exhibition in public spaces that are easily accessible to a wide audience. It encompasses a broad spectrum of creative works, from monumental sculptures adorning city squares to intricately painted murals on the sides of buildings and even interactive installations in parks or transportation hubs. What distinguishes public art is its exceptional capacity to break free from the boundaries of conventional art world settings and engage with people in their daily lives. It serves as a powerful means of communication, capable of conveying a wide range of ideas, emotions and messages to the community at large. Public art plays a pivotal role in shaping the cultural identity of a place, fostering a sense of shared heritage and collective memory. Beyond aesthetics, it encourages public discourse, invites reflection and often serves as a catalyst for dialogue on various social, political and environmental issues. By seamlessly integrating artistic creativity with the fabric of our cities and communities, public art enriches the urban landscape, stimulates imagination and contributes significantly to the cultural vitality of our society.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / National Palace Mural by Diego Rivera

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / National Palace Mural by Diego RiveraThe Pioneers: Diego Rivera and the Birth of Public Art

For centuries, the experience of art had been predominantly confined to the hallowed halls of religious institutions and the opulent chambers of the elite. In the Renaissance period, masterpieces like frescoes and altarpieces adorned churches and palaces, serving as expressions of faith and symbols of power. However, as the world moved into the 20th century, a transformative shift in the art world was on the horizon, led by visionaries like Diego Rivera. A towering figure in the Mexican muralist movement, Rivera played a pivotal role in democratising art by ushering it out of the cloisters of tradition and into the open arms of the public. Rivera's murals, characterised by their grand scale and rich social commentary, were a radical departure from the conventional art forms of his time. He believed that art should no longer remain a privilege of the privileged few but should become an integral part of public life, accessible to all. Adorning public buildings and spaces across Mexico, his murals told vivid stories of history, culture and societal struggles. His monumental works, such as those at the National Palace in Mexico City, transformed public spaces into places of reflection and inspiration. These murals were powerful instruments of communication that resonated with ordinary people. Rivera's vision was to use art as a catalyst for social change, fostering a sense of collective pride and consciousness among the masses.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / SAMO©

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / SAMO©"SAMO 4 The So-Called Avant Garde": Basquiat's Street Art Revolution

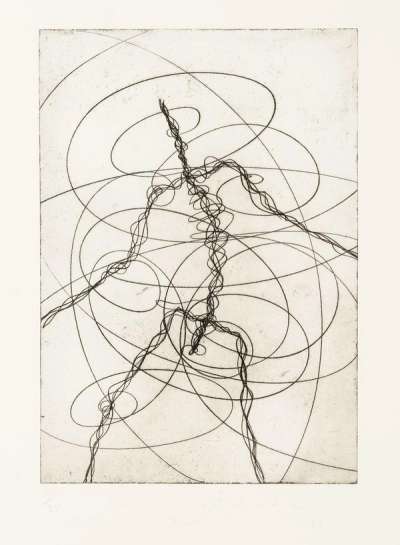

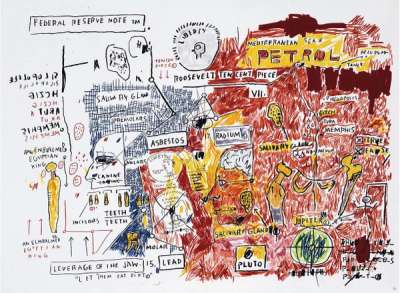

In the late 1970s, in the bustling streets of New York City, a cryptic and enigmatic artistic movement known as SAMO emerged. Standing for "Same Old Shit", the project was the brainchild of two young artists: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Al Diaz. This artistic partnership gave rise to a street art phenomenon that would challenge the status quo and lay the groundwork for Basquiat's later success as a renowned artist. SAMO was not just a tag sprayed onto the walls of lower Manhattan; it was a poetic manifesto, filled with scathing critique of the conformity and complacency observed in both the art world and society at large. Basquiat and Diaz used SAMO as a platform to express their disillusionment with the mundane and the banal. Their messages were often witty, poetic and biting, challenging viewers to question the meaning behind everyday existence.

What set SAMO apart from conventional graffiti was its philosophical depth and intellectual commentary, presenting ordinary viewers with thought-provoking statements that transcended the boundaries of traditional street art. The messages were delivered in a distinctive visual style, with Basquiat's unique blend of symbols, text and imagery foreshadowing his future success as a visual artist. Despite its ephemeral nature and the transient medium of the streets, SAMO managed to capture the attention of a growing audience. Basquiat's involvement with SAMO was a pivotal moment in his artistic journey, serving as a precursor to his prolific career as a painter and an embodiment of his commitment to challenging artistic conventions.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Reproduction of Keith Haring's AIDS mural in Barcelona 1989.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Reproduction of Keith Haring's AIDS mural in Barcelona 1989.Keith Haring's Murals: Art as Activism

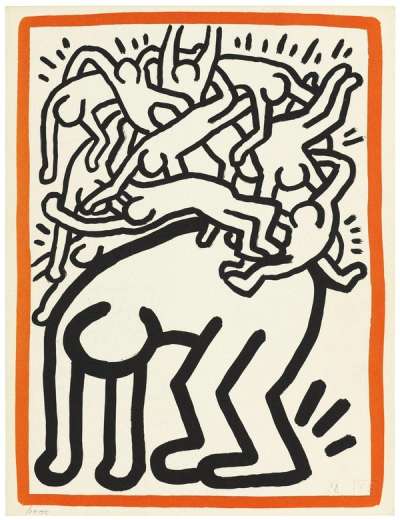

Keith Haring, a prodigious artist of the 1980s, left his mark on the world of art with his iconic and socially charged murals, and his work is a testament to the power of art when wielded as a tool of activism. Haring's journey began as a graffiti artist in the subways of New York City, but it was his transition to creating murals that brought his art to the forefront of contemporary societal discourse. Like most of Haring's art, his murals were characterised by their vibrant colours, bold lines and a distinctive visual language that fused elements of street art, pop culture and contemporary political commentary. While his art often appeared deceptively simple, it carried profound messages addressing pressing social issues, including AIDS awareness, LGBTQ+ rights, apartheid and nuclear disarmament. Haring's murals were a call to action, a demand for justice, awareness, equality and human rights.

One of the remarkable aspects of Haring's work was his commitment to accessibility. He believed that art should not be confined to the walls of elite galleries but should be embraced by the public at large. To this end, he painted numerous public murals in cities around the world, collaborating with local communities and turning urban spaces into open-air galleries. These murals served as beacons of hope and enlightenment, challenging obsolete norms and advocating for change. Haring's art-as-activism approach was a reflection of his belief that artists had a moral obligation to engage with the issues of their time. Through his murals, he initiated important conversations and inspired countless individuals to take a stand for social justice. His work resonated with people from all walks of life, transcending barriers of language and culture and raising awareness about the most relevant issues of his time.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / Season's Greetings © Banksy 2018

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / Season's Greetings © Banksy 2018Banksy's Oeuvre: Provocation and Mystery on the Streets

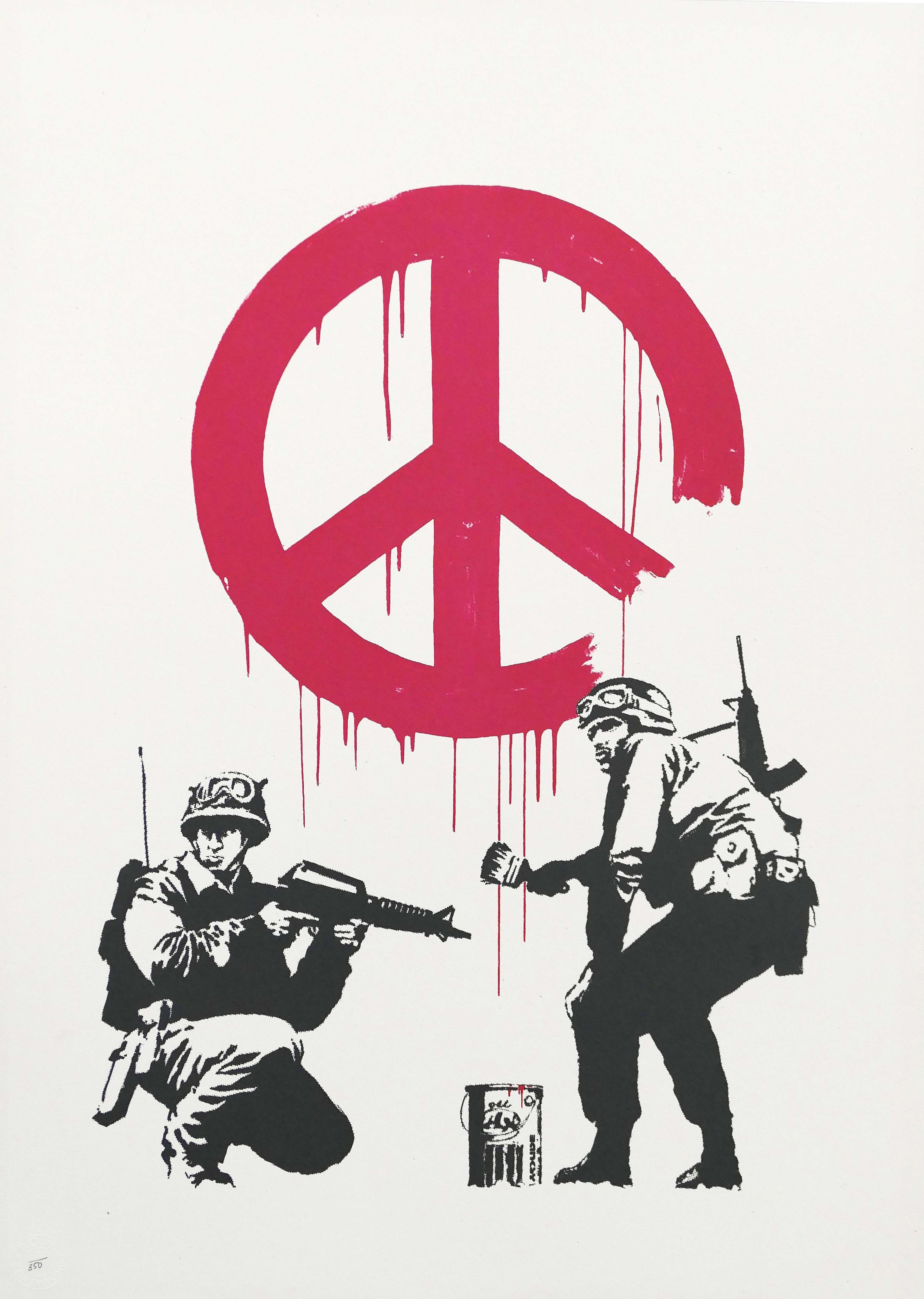

The elusive and enigmatic street artist Banksy has carved a unique niche in the world of public art through his provocative and intriguing works. His oeuvre is composed of a compelling fusion of artistry, social commentary and a penchant for subversion that has captivated audiences worldwide. At the heart of Banksy's art is his anonymity: operating primarily in the shadows, his true identity still remains unknown, allowing his work to speak for itself without the trappings of celebrity that many artists face in the art world. Banksy's anonymity is itself a commentary on its obsession with persona and recognition, highlighting the power of the message over the messenger. Public spaces serve as the canvas for many of Banksy's works, and much of his art is accessible to all regardless of their socio-economic status or background. People stumble upon his pieces in unexpected places: each new piece carries a sense of anticipation and excitement, sparking conversations and engaging the public in a way that's entirely different from the gallery experience.

What distinguishes Banksy's public art is its fearlessness, its confrontation of societal norms and outspokenness on political issues. His pieces often challenge authority, question the status quo and confront overlooked or uncomfortable truths. Whether it is his thought-provoking stencilled images on the walls of war-torn Gaza, a poignant mural on immigration in the heart of London or satirical street art commenting on consumerism and surveillance culture, Banksy's work consistently pushes boundaries and provokes critical thought. His works serve as a reminder that art, when unleashed in the streets, can be a potent instrument of social commentary, a catalyst for change, and a source of inspiration for all who encounter it. In an ever-evolving world, Banksy's work demonstrates the enduring relevance of street art in shaping the cultural conversation.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Angel Of The North, Gateshead © Antony Gormley 2010

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Angel Of The North, Gateshead © Antony Gormley 2010Antony Gormley's Angel of The North: A Monumental Presence

1994 Turner Prize winner Antony Gormley is widely celebrated for his exploration of the human form and its relationship with space. Born in London in 1950, his work often focuses on the human body, using it as a vehicle to explore themes of existence, identity and our place in the broader universe. Gormley is best known for his large-scale, public installations, such as the iconic Angel of the North in Gateshead, England – a quintessential example of public art that has become a renowned symbol of the UK. The sculpture’s monumental scale, with a height of 20 metres and a wingspan of 54 metres, makes a dramatic visual statement in the landscape and is constructed from weathering steel, which develops a rust-like yet non-corrosive appearance. The Angel resonates with the industrial heritage of the area, once dominated by shipbuilding and mining industries, now evolving and growing.

The sculpture holds a profound cultural and historical significance, acting as a welcoming figure to the North East of England. The transformation from an industrial to a post-industrial society is a theme commonly explored in public art, reflecting the evolving identity of communities and regions. Initially met with some opposition and controversy, the sculpture has grown into a cherished emblem of the area, illustrating how public art can evolve in public perception and become an integral part of a community's identity. Gormley was also involved in a Fourth Plinth public sculpture, which actively engaged with the audience.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / Pumpkin © Yayoi Kusama 2016

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / Pumpkin © Yayoi Kusama 2016Yayoi Kusama's Outdoor Installations: Infinite Creativity

Yayoi Kusama, a visionary Japanese artist, is renowned for her unique and mesmerising installations that exhibit her signature style of polka dots, vibrant colours, and infinite mirror reflections. Her outdoor installations are a testament to her infinite creativity and her ability to transform public spaces into immersive, experiential realms. Kusama's outdoor sculptures are often large and whimsically shaped, ranging from oversized pumpkins to flowers, largely adorned with her iconic polka dot pattern. These works are interactive, inviting viewers to walk around and engage with them – especially on social media. The scale and placement of these sculptures in natural settings or urban landscapes create a playful and surreal experience. By placing her fantastical creations in open spaces, Kusama blurs the boundaries between the natural and the artificial, the real and the imagined. This interaction highlights the harmony and conflict between human creations and the natural world.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / The Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / The Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar SquareLondon's Fourth Plinth

The Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square represents one of the most renowned and thought-provoking public art projects in the UK. Situated in the northwest corner of the square, the plinth was originally designed in 1841 to hold an equestrian statue of William IV. However, due to insufficient funds, it remained empty for over 150 years. In 1998, began a new chapter in its history when the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce initiated the Fourth Plinth Project. Since then, this vacant plinth has since become a significant site for contemporary art, hosting a rotating series of commissioned works.

The Fourth Plinth has hosted a diverse range of temporary public artworks, each typically displayed for about 18-24 months. These have included Yinka Shonibare's Nelson's Ship in a Bottle, a scale replica of HMS Victory with sails made of African textile patterns, and David Shrigley’s Really Good, a 23-ft bronze sculpture of a human hand in a thumbs-up gesture, with the thumb greatly elongated. A more recent example is Heather Phillipson’s THE END, a giant swirl of whipped cream topped with a cherry, a fly and a drone. These artworks often stimulate public debate and reflect contemporary social and political themes.

The Fourth Plinth programme has become a highly respected and anticipated event in London's cultural calendar. The changing nature of the artworks mirrors the dynamic and evolving nature of contemporary art. The plinth provides a platform for artists to engage with a broad audience, often sparking conversations about the role of art in public spaces and its capacity to address societal issues. One of the unique aspects of the Fourth Plinth project is its engagement with the public: the selection process involves public consultation, and the artworks often become focal points for discussion, critique and interaction. This model of public art fosters a sense of community ownership and participation in the cultural and artistic life of the city.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Jeff Koons' Bouquet of Tulips in Paris

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Jeff Koons' Bouquet of Tulips in Paris Challenges in Public Commissions: Jeff Koons' Bouquet Of Tulips

Jeff Koons' Bouquet of Tulips faced several challenges particular of public art commissions, highlighting the complexities involved in realising such projects – especially those with deep emotional and symbolic significance. Unveiled in Paris in 2019, the sculpture was created by Koons as a gesture of solidarity and remembrance for the victims of the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, including those at the Bataclan theatre. The sculpture features a hand holding a bouquet of colourful tulips, intended to symbolise remembrance, optimism and healing. Despite its noble intent, the sculpture faced significant public and critical backlash, and critics argued that the artwork was inappropriate and insensitive to the tragedy's gravity. Some viewed it as a superficial response to a profound and painful event, while others criticised its aesthetic qualities, questioning whether its flamboyant and colourful design was suitable as a memorial for such a sombre occasion. One of the critical challenges in public art commissions, particularly memorials, is navigating cultural and contextual sensitivities. In this case there was a feeling among some Parisians that an American artist might not fully grasp the depth of the tragedy's impact on the local community.

The sculpture's installation also encountered logistical and financial issues, and there were debates over the artwork's placement, with concerns about its size and visual impact on the chosen site. Additionally, the project's financing became a point of contention; while the sculpture was a gift from Koons, the cost of its production and installation (which was significant due to its large scale and intricate design) had to be met through private donations and public funds. This aspect raised questions about the allocation of resources for public art, especially for works gifted by internationally renowned artists. Now, the work serves as a case study of the challenges faced in public art commissions: it illustrates the need for careful consideration of public sentiment, cultural context, logistical planning and financial implications in creating artworks meant for public spaces – especially for works that aim to honour and remember significant events.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Spider © Louise Bourgeois

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Spider © Louise BourgeoisThe Legacy of Public Artists: The Democratisation of Culture

It is evident that public art plays a crucial role in the democratisation of culture: the aforementioned artists and platforms have challenged traditional boundaries, bringing art out of the exclusive confines of galleries and museums and into the open shared spaces of everyday life. Public art serves as a catalyst for broader cultural engagement, making art accessible to a diverse audience regardless of their background or knowledge of art. It democratises culture by providing a common ground for dialogue, reflection and shared experience. Art in public spaces often becomes a part of the community’s identity, reflecting its values, struggles, and aspirations.

Moreover, the controversies and discussions that often accompany public art installations highlight the importance of public engagement and the role of art in reflecting and shaping societal narratives. Whether it's through monumental sculptures that redefine cityscapes or installations that invite introspection and communal interaction, public art plays a crucial role in fostering a more inclusive and participatory cultural landscape.