David Hockney & Bridget Riley: Catalysts of Contemporary Art

Image © Tate / Portrait Of An Artist (Pool With Two Figures) © David Hockney 1972 & Rose © Bridget Riley 1978

Image © Tate / Portrait Of An Artist (Pool With Two Figures) © David Hockney 1972 & Rose © Bridget Riley 1978Market Reports

David Hockney and Bridget Riley, two titans of British Post-War & Contemporary Art, pioneered movements which altered the course of art history. While Hockney is considered one of the founding fathers of British Pop Art, Riley is championed as the mother of the Op Art movement. Though these two movements are as idiosyncratic as the artists themselves, Hockney and Riley broke with tradition to create original, innovative, and diverse works of art.

Check out our latest Modern British Prints Market Report for valuable insight into the 2023 performances of David Hockney and Bridget Riley’s art as financial assets, alongside market analysis of L.S. Lowry.

Born just six years apart, Hockney and Riley are amongst a generation of British artists who laid the groundwork for Contemporary Art as we know it today. The pair developed a very different sense of style throughout the course of their respective careers, and both played a transformative role in the art world. Both of these artists are still alive and producing work to this date, acting as an inspiration to other artists of our age.

Here we look to the careers of these two influential artists, from their formative years in training to today:

Image © Art UK/ Labor Omnia Vincit © David Hockney 1956-57 & Image © Sotheby's / Pink Landscape © Bridget Riley 1960

Image © Art UK/ Labor Omnia Vincit © David Hockney 1956-57 & Image © Sotheby's / Pink Landscape © Bridget Riley 1960Hockney & Riley's Beginnings

Early Years

Bridget Riley was born in 1931 in Norwood, South London. The daughter of a printer, Riley's family relocated to Lincolnshire until her father was drafted into the army. Alongside her mother, sister, and aunt, Riley moved to Cornwall during the Second World War. Riley was schooled at Cheltenham Ladies College, where she developed a keen interest in the arts of drawing and painting. It was in Cornwall, however, that Riley spent her time observing the changing light and colours in nature - something which would come to greatly shape her oeuvre.

David Hockney, on the other hand, was born in 1937 in Bradford, Yorkshire. Hockney was born to Laura and Kenneth Hockney, who was a conscientious objector in the Second World War. From an early age, Hockney was encouraged by his parents to be creative, and he soon found inspiration in the likes of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Hockney was schooled at Bradford Grammar School and went on to train at the Bradford College of Art, where the artist's career began to take shape.

Read more about the places that shaped them:

Bridget Riley's Artistic Journey: From Cornwall to Egypt

David Hockney's Artistic Journey: From Yorkshire to Los Angeles

Art School & Establishing Style

Though Hockney and Riley initially studied at different institutions, both artists earned a place at the esteemed Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. Riley's studies at the RCA, between 1952-55, were difficult and frustrating. For Riley, the RCA's teaching proved unrewarding and the institution rather stifled her individuality. For Hockney, however, the RCA was an exciting and fulfilling experience. From 1959, Hockney studied here alongside Peter Blake and Allen Jones, and experimented with different media and styles. So successful was Hockney's time at the RCA that he received a gold medal in the graduate competition.

Of course, neither Riley nor Hockney established their true style at the Royal College of Art. Riley's early works were highly figurative, until she came into contact with French Pointilism, which inspired her fascination with colour and optical effects. This is something we certainly see in her 1960 Pink Landscape, which is based on Seurat’s iconic Le pont de Courbevoie (1886). Though the work is one of her most famous, it is certainly divergent from her later Op-Art works.

Likewise Hockney's early works, like many of his peers at the RCA, were heavily informed by Abstract Expressionism. As Hockney himself recalled, “Young students had realised that American painting was more interesting than French painting. The idea of French painting disappeared really, and American abstract expressionism was the great influence. So I tried my hand at it, I did a few pictures, about twenty on three feet by four feet pieces of hardboard that were based on a kind of mixture of Alan Davie cum Jackson Pollock cum Roger Hilton. And I did them for a while, and then I couldn't. It was too barren for me.” We see the influence of Abstract Expressionism and British artists like Francis Bacon in his Labor Omnia Vincit which, like Bridget Riley's early work, are very different to the bright, colourful works of his later career.

Op Art

Bridget Riley's Rise to Success

During the Swinging Sixties, both Hockney and Riley consolidated the style that would propel them to international acclaim. For Riley, that style came to be known as Op Art. Working exclusively in monochrome until the late 1960s, Riley's Op Art was characterised by simple geometric shapes that created optical illusions. Riley's breakthrough work was her 1961 Movement In Squares, a black and white grid of squares in varying widths which have the appearance of collapsing into the canvas. According to Riley, the experimental work was made partly from intuition, and she created something “on the paper that I had not anticipated.”

From this point onwards, the Op Artist was met with success for her optically challenging and dizzying works. In 1962, she had her first solo exhibition at Gallery One in London, which led to award wins in 1963. The following year, Riley was invited to show her works at the “Next Generation” exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery alongside Hockney. In 1965, Riley's paintings were shown at the Museum of Modern Art in an exhibition titled “The Responsive Eye”, which focused on the perceptual qualities of art. One of Riley's paintings was used for the catalogue cover of this genre-defining exhibition, and led to her fame and success in the US.

Riley's bold visual experimentation and mastery of colour culminated in Gala (1974), a work that mimics the dynamic flow of a rippling surface, exemplifying the pinnacle of the Op Art movement. Decades later, in the 2022 Modern British Art Evening Sale at Christie’s London, Gala set a new auction record for Riley when it significantly exceeded its estimated value of £3.5 million, selling for an impressive £4.4 million. This sale not only marked Gala as Riley's highest-selling piece to date, but also underscored her enduring influence and the timeless appeal of her work.

Image © Art UK / Peter Getting Out Of Nick's Pool © David Hockney 1966

Image © Art UK / Peter Getting Out Of Nick's Pool © David Hockney 1966British Pop Art

David Hockney's Establishment of British Pop

Much like Riley, the 1960s proved a defining and watershed decade for David Hockney. The artist began to step away from the institutional norm of Abstract Expressionism, opting for subject which were informed by his own life experiences. Hockney was an openly queer artist, and much of his early works celebrate gay relationships and queer culture. One such work that expresses this intimate approach is We Two Boys Together Clinging, an oil on board piece inspired by a poem by Walt Whitman that conveys the literary impulse in Hockney's work. Within just three years after the creation of this particular work, however, Hockney began painting people and places personal to him. In 1963, Hockney was the sole artist showing at his first exhibition at Kasmin's gallery in London, titled “David Hockney: Pictures with People In” - a nod to the artist's preferred subject matter from this point onwards.

Perhaps the most important year in this decade to Hockney's development as an artist was 1964. In this year, Hockney moved to California, having never before visited. Within a week of his arrival, Hockney had passed his driving test, bought a car, and became absorbed in LA life. In the same year, Hockney took up Polaroid photography and created his first swimming pool paintings. Though he returned to the UK in early 1965, his mind and heart was still in LA, and the artist soon returned to the US later in the year.

It was during this time in California that Hockney developed his British iteration of Pop Art. Guided by the rich colours and brilliant light of his surroundings, Hockney's work took on a new dimension during the 1960s. Though we refer to Hockney's art as “British Pop Art”, his style and subject matter has always been far more nuanced than that. From the 1960s onwards, Hockney's work was intimate, innovative, and perpetually reflective of the artist's many passions.

Here, we see Hockney and Riley together at an exhibition of their works at the Robert Fraser gallery in London:

1960s Swinging Art Gallery London - Bridget Riley, David Hockney, Robert Fraser, Charlie Watts (@Kinolibrary via YouTube).

Ways of Seeing

Though Hockney and Riley's art certainly took very different forms in the 1960s, both had a keen interest in the perceptual qualities of their work. In Hockney's case, this was partly owed to his work in theatre stage and set design throughout his career. Hockney has been commissioned to produce scenography for prestigious institutions such as the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. This foray into design certainly impacted his two-dimensional art practice, as we see in avant-garde works like Four Part Splinge, from his Some New Prints series. These works toy with texture, materiality, and perspective - creating a psychedelic effect not entirely dissimilar to Riley's work. The sheer breadth of Hockney's work - which he still adds to today - is testament to his ceaseless exploration of new ways of seeing.

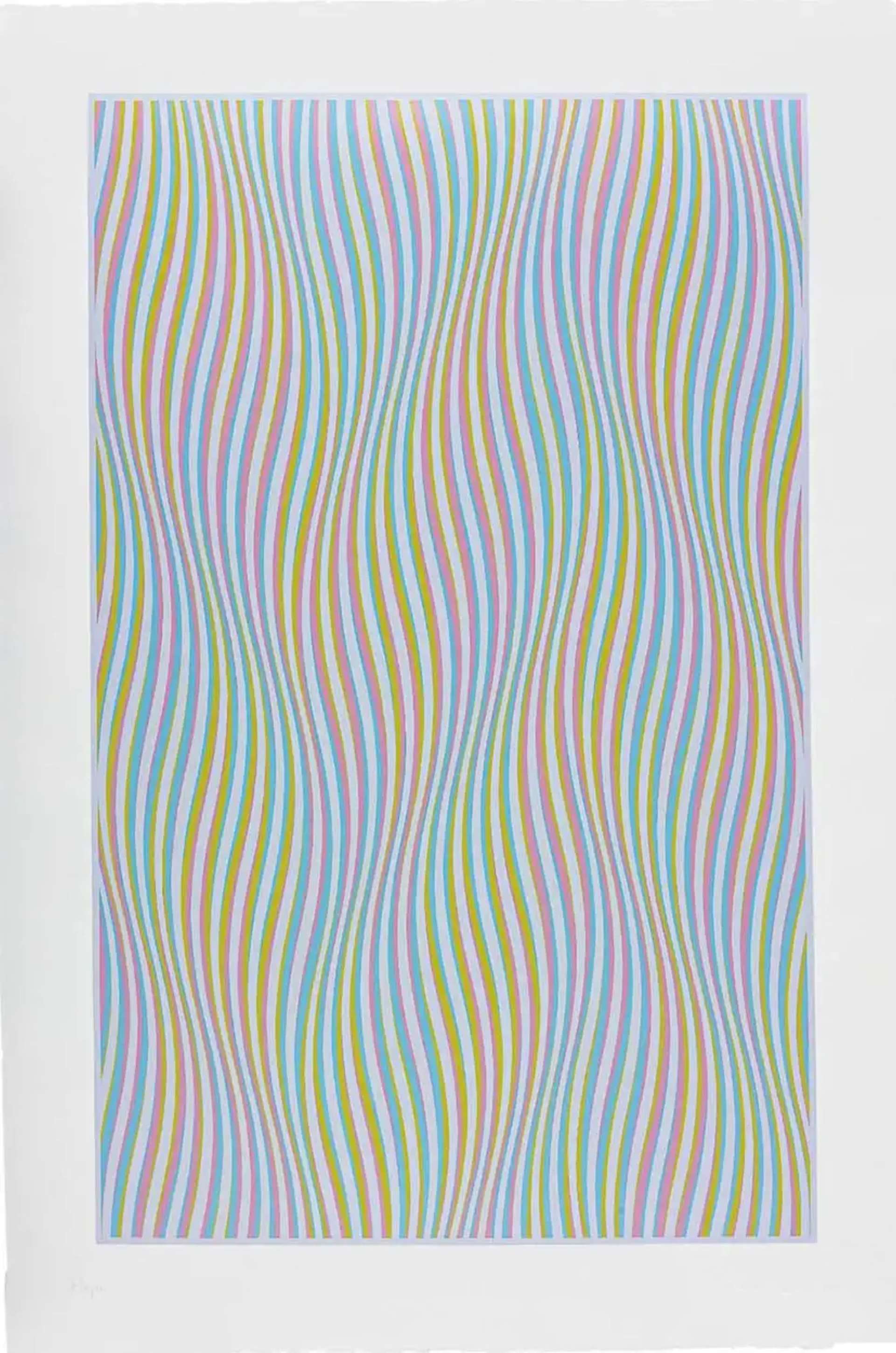

Riley, on the other hand, dedicated her lifelong oeuvre to Op Art. From the 1970s, she began experimenting with colour in these perceptually challenging works. Unlike Hockney's bold Pop colour scheme, Riley often opted for mixed hues to heighten the optical sense of movement in her works - as we see in Elapse. Riley implemented these colours not only to heighten the dizzying effects of her compositions, but also to effect an emotional response in her viewers.

Technology & Innovation

Throughout their careers, both Hockney and Riley have been keen to break with tradition and innovate. While Riley doesn't produce so many prints and paintings today, her existing artwork has a timeless appeal - challenging the senses of every viewer. Hockney still produces work to this date - mainly on his trusty iPad - always exploring new ways of representing.

In September, 2024, Phillips' David Hockney sale saw sustained interest in Hockney's The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate series, which he first created on his iPad in 2011. In this recent auction, one piece from the series, initially estimated at £70,000-£90,000, achieved over 50% above the high estimate, ultimately selling for £150,000, or nearly £190,000 with fees, underscoring the popularity of Hockney’s digital artwork in today’s art market.

Both Hockney and Riley, two titans of Contemporary Art, are leading lights of their respective genres, and have made poignant and lasting changes to the course of art history.